Monthly Summaries

Issue 35, November 2019

[PDF]

A bushfire remains under emergency in Harrington in New South Wales, Australia. Photo: Kelly-Ann Oosterbeek.

November media attention to climate change and global warming at the global level remained relatively steady from October 2019 coverage. However, across the globe, November 2019 news articles and segments about climate change and global warming was up 64% from a year earlier (November 2018). The ongoing stream of stories also continued for the most part in Europe, where regional coverage was steady, as was national-level coverage in the Germany, UK and Sweden as examples. An exception to this trend was coverage in Spain, where news accounts – some anticipating the United Nations (UN) Madrid-based round of climate talks (COP25) beginning December 2 – increased a bit, up 7% from October 2019.

Focusing further at the country level, on the heels of the previous month’s Canadian Federal election (see October 2019 summary for more details), coverage across Canada decreased by a third, though it still remained more than double the quantity of coverage a year previous (November 2018). Similarly, record levels of coverage in New Zealand in October 2019 (see October 2019 summary for more details) were down nearly 24% in November 2019, yet still up 72% from the previous November. In contrast, coverage was up 5% in the United States (US), up 13% in India and up 25% in Japan from the previous month of October.

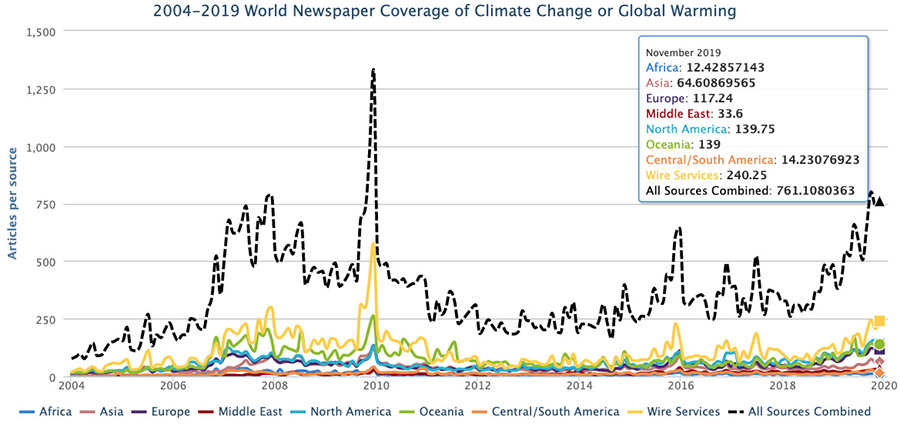

Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through November 2019.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in one-hundred print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through November 2019.

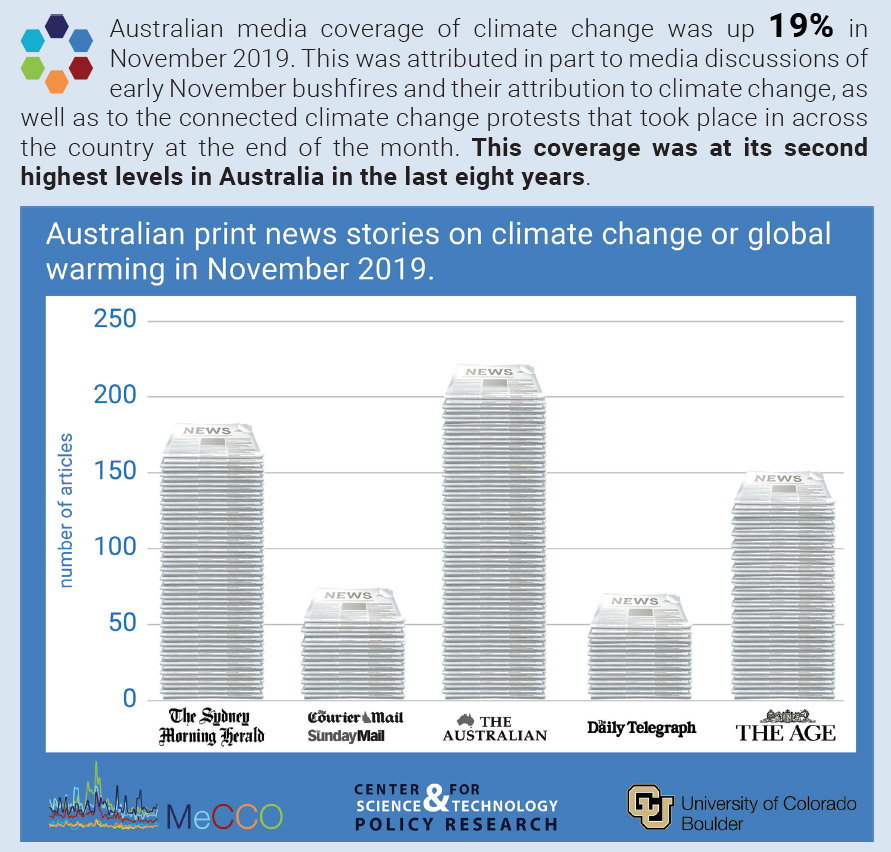

In particular, Australian media coverage of climate change was up 19% in November 2019. This was attributed in part to media discussions of early November bushfires and their attribution to climate change, as well as to the connected climate change protests that took place in across the country at the end of the month. This coverage was at its second highest levels in Australia in the last eight years. The only month of higher coverage during that stretch were May 2019 levels, attributed in most part to the May 18 Australian elections where climate change played a big part (see May 2019 summary for more details). Figure 2 shows the number of stories per outlet in November 2019 (The Sydney Morning Herald, Courier Mail & Sunday Mail, The Age, The Australian and The Daily Telegraph & Sunday Telegraph).

Figure 2. Number of news stories per outlet in November 2019 across the Australian newspapers The Sydney Morning Herald, Courier Mail & Sunday Mail, The Age, The Australian and The Daily Telegraph & Sunday Telegraph.

More specifically, early in November the Australian government declared a state of emergency for the east coast as wildfires that raged through the state of New South Wales, not far from Sydney. Numerous stories linked these wildfires to climate change. For example, journalists Jacob Miley, Thomas Morgan and Chris Clarke from The Courier Mail quoted Queensland Fire and Emergency Services Commissioner Katarina Carroll who said, “The combination of the climate, the heat, the fire is just absolutely horrendous”. Meanwhile, a Sydney Morning Herald Editorial entitled ‘Talking about climate change is not an insult to bushfire victims’ pointed out “In a week when all Australians are concerned for the lives and property of residents and firefighters in NSW and Queensland who continue to face the threat of catastrophic bushfires, climate change must be part of the discussion. Of course, in the short term, as both Prime Minister Scott Morrison and NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian said over the weekend, the main focus should be on expressing sympathy for people who are directly affected and planning an emergency response. But scientists agree that climate change has caused a long-term increase in extreme bushfire weather and made the fire season longer in many parts of Australia. So it is something we should talk about. It is not a sign of indifference to the victims of bushfires or political point-scoring to raise the issue of climate change. It is common sense. Without a rational assessment of the causes and trends of bushfires, we will only increase the likelihood of more tragedies in the future. So if politicians want to reinforce their compassion for the victims of bushfires, they should talk about the link to climate change sooner rather than later. The fire season will last for months”. And pointing to the human and property damage, journalist David Aaro from Fox News reported, “Wildfires have ripped through Australia's most populated state, claiming three lives, destroying at least 150 homes and forcing more than 1,300 people to flee, according to officials. Over 35 people have been injured, including 16 of the 1,500 firefighters battling fires across New South Wales”.

More specifically, early in November the Australian government declared a state of emergency for the east coast as wildfires that raged through the state of New South Wales, not far from Sydney. Numerous stories linked these wildfires to climate change. For example, journalists Jacob Miley, Thomas Morgan and Chris Clarke from The Courier Mail quoted Queensland Fire and Emergency Services Commissioner Katarina Carroll who said, “The combination of the climate, the heat, the fire is just absolutely horrendous”. Meanwhile, a Sydney Morning Herald Editorial entitled ‘Talking about climate change is not an insult to bushfire victims’ pointed out “In a week when all Australians are concerned for the lives and property of residents and firefighters in NSW and Queensland who continue to face the threat of catastrophic bushfires, climate change must be part of the discussion. Of course, in the short term, as both Prime Minister Scott Morrison and NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian said over the weekend, the main focus should be on expressing sympathy for people who are directly affected and planning an emergency response. But scientists agree that climate change has caused a long-term increase in extreme bushfire weather and made the fire season longer in many parts of Australia. So it is something we should talk about. It is not a sign of indifference to the victims of bushfires or political point-scoring to raise the issue of climate change. It is common sense. Without a rational assessment of the causes and trends of bushfires, we will only increase the likelihood of more tragedies in the future. So if politicians want to reinforce their compassion for the victims of bushfires, they should talk about the link to climate change sooner rather than later. The fire season will last for months”. And pointing to the human and property damage, journalist David Aaro from Fox News reported, “Wildfires have ripped through Australia's most populated state, claiming three lives, destroying at least 150 homes and forcing more than 1,300 people to flee, according to officials. Over 35 people have been injured, including 16 of the 1,500 firefighters battling fires across New South Wales”.

US President Trump holds up a "Trump Digs Coal" sign at a West Virginia rally. Photo: Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images. |

Then, on November 29 there were large demonstrations in over 100 towns and cities across the country that sought to raise these issues of bushfires and climate change in the realm of policy decision-making. Thousands of students participated in events, and media coverage was prominent. There were numerous angles taken by Australian media outlets. For example, ahead of the protest date The Australian focused on the disruptions that the climate demonstrations generated, noting, “Their plans to blockade a major resources conference in Perth have prompted police to deploy security typically reserved for heads of state, but climate activists insist they're committed to a peaceful demonstration. Environmental groups including Extinction Rebellion are promising a significant presence at Perth Convention Centre on Wednesday, where attendees will include the chief executives of BHP, Woodside Energy and Chevron Australia”. On the day of the actions, Sydney Morning Herald journalist Konrad Marshall reported on who he called ‘the climate strike kids’ and their demands. Then, after the event journalist Lydia Lynch from The Age observed, “The owner of a south-east Queensland mountain resort that narrowly escaped a "glowing ribbon" of fire this month has added his voice to a chorus of activists begging the government to declare a climate emergency. Mt Barney Lodge owners Innes and Tracey Larkin watched on as fires ravaged parts of the national park this month ... Mr Larkin joined a few hundred people for a "sit-in" protest at Queens Gardens in the CBD on Friday afternoon, as part of a national day of action. Protests were also held outside Liberal Party headquarters in Sydney and Victorian Parliament in Melbourne”. Meanwhile, Courier Mail columnist Peggy Noonan conceded that “what climate protesters are fighting for is indisputably something we should all want: a healthier planet”. As an example of additional coverage from outside Australia, journalist Calla Wahlquist from The Guardian noted, “A teenager whose family home burned down in the New South Wales bushfires has delivered a message to Scott Morrison at a climate emergency protest outside the Liberal party headquarters, saying: “your thoughts and prayers are not enough”. Shiann Broderick, from Nymboida, said government inaction on the climate crisis had “supercharged bushfires”. “People are hurting,” she said in a statement before the protest on Friday at the party’s Sydney headquarters on Friday. “Communities like ours are being devastated. Summer hasn’t even begun””. Moreover, Associated Press journalist Frank Jordan noted that these demonstrations were also timed to take place ahead of the United Nations climate talks in Madrid that began on December 2 concurrently in cities around the world. He began the article writing “Protesters in cities across the world staged rallies Friday demanding leaders take tougher action against climate change, days before the latest global conference, which this year takes place in Madrid. The rallies kicked off in Australia, where people affected by recent devastating wildfires joined young environmentalists protesting against the government’s pro-coal stance”.

In November (much like in October), political and economic connections with climate issues continued to drive a significant portion of overall media coverage of climate change around the world. To illustrate, media attention spiked in early November when the Trump Administration officially filed their paperwork to the UN to initiate the formal process of withdrawing the United States (US) from the Paris Agreement. This set forward a process where the US officially will be removed on November 4, 2020 (one day after the US Presidential election). For example, journalist Connor Finnegan from NBC News reported, “The formal notification comes over two years after President Donald Trump announced he would pull the US out of the agreement, criticizing it as imposing an unfair burden on the US and doing little to halt climate change-causing emissions from other countries – claims that critics say mischaracterize the agreement. The agreement ... seeks to limit global temperature increases to less than 2 degrees Celsius, with each country setting its own nonbinding emission targets and reporting on its progress to reduce them”. Meanwhile, journalist Rebecca Hersher from US National Public Radio noted, “The Trump administration has formally notified the United Nations that the US is withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement. The withdrawal will be complete this time next year, after a one-year waiting period has elapsed. "We will continue to work with our global partners to enhance resilience to the impacts of climate change and prepare for and respond to natural disasters," Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said in a statement Monday. Nearly 200 countries signed on to the agreement in 2015 and made national pledges to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Each country set its own goals, and many wealthy countries including the US also agreed to help poorer countries pay for the costs associated with climate change. The US is now the only country to pull out of the pact”.

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern speaks in the Lower House during the third reading of the Zero Carbon Bill. Photo: Getty Images. |

In contrast, in November the New Zealand government pressed ahead in a bipartisan manner to confront climate challenges. Early in the month, a historic bill passed 119-1 to operationalize a pact to decarbonize by mid-century. For example, in an article entitled ‘'This is our nuclear moment': NZ passes climate change law’, journalist Ben McKay from The Sydney Morning Herald reported, “New Zealand has reached agreement on climate change policy, passing the Zero Carbon Bill in Parliament. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern's government landed their flagship climate legislation on Thursday with the support of the opposition National party, which she hopes will ensure the longevity of the law. It is hoped the bill's success sets a course for New Zealand to radically reduce emissions by the year 2050”. Meanwhile, in The New Zealand Herald, journalist Audrey Young quoted Prime Minister Ardern who said, “"And I am proud at least that ... we're no longer having the debate over whether or not that is the case. We're merely debating what it is we do about it." Ardern went on to say she absolutely believed climate change was the "biggest challenge of our time" and the "nuclear moment" for this generation”.

In mid-November, the International Energy Agency released their annual World Energy Outlook report. The report stated the importance of energy transitions, and the connections to a changing climate generated many news reports. For example, New York Times reporter Brad Plumer wrote, “Wind turbines, solar panels and electric vehicles are spreading far more quickly around the world than many experts had predicted. But this rapid growth in clean energy isn’t yet fast enough to slash humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions and get global warming under control. That’s the conclusion of the International Energy Agency, which on Tuesday published its annual World Energy Outlook, an 810-page report that forecasts global energy trends to 2040. Since last year, the agency has significantly increased its future projections for offshore wind farms, solar installations and battery-powered cars, both because these technologies keep getting cheaper and because countries like India keep ramping up their clean-energy targets. But the report also issues a stark warning on climate change, estimating that the energy policies countries currently have on their books could cause global greenhouse gas emissions to continue rising for the next 20 years. One reason: The world’s appetite for energy keeps surging, and the rise of renewables so far hasn’t been fast enough to satisfy all that extra demand. The result: fossil fuels use, particularly natural gas, keeps growing to supply the rest”.

Shell’s Brent Bravo oil rig arrives on Teesside in in North East England for decommissioning, June 2019. Photo: Ian Forsyth/Getty Images. |

Also, in mid-November, the European Union announced that over the next 24 months they will phase out their investments in fossil fuel projects, ending €2 billion ($2.2B) of yearly investments. This sparked media interest throughout Europe and around the world. For example, Guardian journalists Jillian Ambrose and Jon Henley reported, “The European Investment Bank has agreed to phase out its multibillion-euro financing for fossil fuels within the next two years to become the world’s first ‘“climate bank”. The bank will end its financing of oil, gas, and coal projects after 2021, a policy that will make the EU’s lending arm the first multilateral lender to rule out financing for projects that contribute to the climate crisis. The decision to stem the flow of capital into fossil fuel projects has been welcomed by green groups as an important step towards the EU’s aim to be carbon-neutral by 2050. The EIB, the world’s largest multilateral financial institution, described its decision as a “quantum leap” in ambition”.

In November, there were signs of trending in a different direction as a report from Global Energy Monitor found that the Chinese government increased its coal output by approximately 5% over the past year and a half while they have plans to continue to expand its coal-fired power in the coming years. Media reported on these findings and developments. For example, Washington Post journalist Gary Shih reported, “When Chinese authorities declared three years ago that they would limit the use of coal energy and canceled more than 100 coal power projects, climate campaigners cheered what seemed to be a sweeping policy reversal for the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter. They may have celebrated too soon. Here on the Shandong Province coastline, cranes perched over a half-built smokestack and two furnaces show how once-suspended coal power projects are being revived — and entering service — across China, tilting the balance of coal power worldwide and worrying climate scientists. In the past two years, China has expanded its coal fleet by 43 gigawatts — roughly the entire coal-fired capacity of Germany — according to Global Energy Monitor, a group that tracks construction in the Chinese power industry using public announcements and satellite images. Excluding China, global coal power capacity would otherwise be dropping as countries in Europe and elsewhere decommission old facilities and switch to other energy sources, the group said in a report released Wednesday”.

In addition to these political and economic media stories about climate change, ecological and meteorological content also shaped media coverage in November. For example – meshing with scientific themes as well – a study from the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences garnered substantial media interest. This study re-examined hurricane damages and links to a changing climate. For example, Associated Press journalist Seth Borenstein wrote, “Big, destructive hurricanes are hitting the US three times more frequently than they did a century ago, according to a new study. Experts generally measure a hurricane’s destruction by adding up how much damage it did to people and cities. That can overlook storms that are powerful, but that hit only sparsely populated areas. A Danish research team came up with a new measurement that looked at just the how big and strong the hurricane was, not how much money it cost. They call it Area of Total Destruction”. As another example, BBC reporter Matt McGrath noted, “Using a new method of calculating the destruction, the scientists say the increase in frequency is "unequivocal". Previous attempts to isolate the impact of climate change on hurricanes have often came up with conflicting results. But the new study says the increase in damage caused by these big cyclones is linked by global warming. Hurricanes or tropical cyclones are one of the most destructive natural disasters. The damage inflicted by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was estimated to be $125bn, roughly 1% of US GDP”.

In November, cultural dimensions also grabbed some of the overall media attention to climate change and global warming. For example, numerous stories covered how the Collins English Dictionary announced that ‘climate strike’ was named its 2019 Word of the Year. They stated that the term’s use has gone up dramatically in the last calendar year, noting the increasing influence of youth-led demonstrations for more significant climate action. To illustrate, journalist Johanne Elster Hanson wrote, “In a year when global protests over the climate crisis were staged from Afghanistan to Vietnam, Extinction Rebellion demonstrations stopped traffic in major cities and Greta Thunberg called for young people to skip school to fight political inaction, “climate strike” has been named Collins Dictionary’s 2019 word of the year. Each year, the dictionary’s lexicographers monitor a 9.5bn word corpus and make a list of 10 new and notable terms. One of these is crowned the word of the year. Climate strike’s definition is “a form of protest in which people absent themselves from education or work in order to join demonstrations demanding action to counter climate change.” The first use of the expression was registered in 2015, when a mass demonstration took place during the UN climate change conference in Paris. However, the phrase only took off in late 2018, when the young Swedish activist Thunberg’s decision to skip school on Fridays in order to protest in front of the national parliament made headlines around the world. In September 2019, an estimated six million people joined the worldwide climate strike, also known as the Global Week for Future. Collins lexicographers noticed a hundredfold increase in the use of climate strike in 2019, the largest of any word on their list”.

In November, cultural dimensions also grabbed some of the overall media attention to climate change and global warming. For example, numerous stories covered how the Collins English Dictionary announced that ‘climate strike’ was named its 2019 Word of the Year. They stated that the term’s use has gone up dramatically in the last calendar year, noting the increasing influence of youth-led demonstrations for more significant climate action. To illustrate, journalist Johanne Elster Hanson wrote, “In a year when global protests over the climate crisis were staged from Afghanistan to Vietnam, Extinction Rebellion demonstrations stopped traffic in major cities and Greta Thunberg called for young people to skip school to fight political inaction, “climate strike” has been named Collins Dictionary’s 2019 word of the year. Each year, the dictionary’s lexicographers monitor a 9.5bn word corpus and make a list of 10 new and notable terms. One of these is crowned the word of the year. Climate strike’s definition is “a form of protest in which people absent themselves from education or work in order to join demonstrations demanding action to counter climate change.” The first use of the expression was registered in 2015, when a mass demonstration took place during the UN climate change conference in Paris. However, the phrase only took off in late 2018, when the young Swedish activist Thunberg’s decision to skip school on Fridays in order to protest in front of the national parliament made headlines around the world. In September 2019, an estimated six million people joined the worldwide climate strike, also known as the Global Week for Future. Collins lexicographers noticed a hundredfold increase in the use of climate strike in 2019, the largest of any word on their list”.

Finally, media accounts in November continued with a focus on scientific themes as well. Examples abounded. Early in the month a statement claiming science’s ‘moral obligation to clearly warn humanity of any catastrophic threat’ was published in BioScience journal that included endorsements by over 11,000 scientists in over 150 countries around planet Earth. Many media outlets covered this statement. For instance, Washington Post journalist Andrew Freedman reported, “A new report by 11,258 scientists in 153 countries from a broad range of disciplines warns that the planet “clearly and unequivocally faces a climate emergency,” and provides six broad policy goals that must be met to address it. The analysis is a stark departure from recent scientific assessments of global warming, such as those of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in that it does not couch its conclusions in the language of uncertainties, and it does prescribe policies. The study, called the “World scientists’ warning of a climate emergency,” marks the first time a large group of scientists has formally come out in favor of labeling climate change an “emergency,” which the study notes is caused by many human trends that are together increasing greenhouse gas emissions”. As another example, journalist Damian Carrington in The Guardian wrote, “The statement is published ... on the 40th anniversary of the first world climate conference, which was held in Geneva in 1979 ....The scientists say the urgent changes needed include ending population growth, leaving fossil fuels in the ground, halting forest destruction and slashing meat eating”.

In mid-November, a paper (with contributions from our MeCCO team) was published in The Lancet, drawing links between climate change and public health. This ‘2019 Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change’ earned substantial media coverage around the world. For example, journalist Jen Christensen from CNN reported, “The climate crisis is already hurting our health and it could burden generations to come with lifelong health problems, a new report finds. It could challenge already overwhelmed health systems and undermine much of the medical progress that has been made in the last century. If the world continues to produce the same amount of carbon emissions, a child born today could be living in a world with an average temperature that's 7.2 degrees Fahrenheit (4 degrees Celsius) warmer by their 71st birthday, according to the report, published Wednesday in the medical journal The Lancet. On any given day, a 7.2-degree difference might not sound like much, but as an average increase in temperature, it would be devastating for our health”. As another example, USA Today journalist Doyle Rice wrote, “The report stated that as temperatures rise, harvests will shrink – threatening food security and driving up food prices. Infants and small children are among the worst affected by malnutrition and related health problems such as stunted growth, weak immune systems, and long-term developmental problems. In addition, children will be especially susceptible to the infectious diseases that rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns will leave in their wake. 2018 was the second-most climatically suitable year on record for the spread of bacteria that cause much of diarrheal disease and wound infection around the world ... Extreme weather events will intensify into adulthood, the report found, with 152 out of 196 countries experiencing an increase in people exposed to wildfires since 2001-04, and a record 220 million more people over 65 exposed to heatwaves in 2018, when compared with 2000. For the world to meet its U.N. climate goals and protect the health of the next generation, the energy landscape will have to change drastically, and soon, the report warned. Nothing short of a 7.4% year-on-year cut in carbon dioxide emissions from 2019 to 2050 will limit global warming to the more ambitious goal of 2.7 degrees F”.

In mid-November, a paper (with contributions from our MeCCO team) was published in The Lancet, drawing links between climate change and public health. This ‘2019 Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change’ earned substantial media coverage around the world. For example, journalist Jen Christensen from CNN reported, “The climate crisis is already hurting our health and it could burden generations to come with lifelong health problems, a new report finds. It could challenge already overwhelmed health systems and undermine much of the medical progress that has been made in the last century. If the world continues to produce the same amount of carbon emissions, a child born today could be living in a world with an average temperature that's 7.2 degrees Fahrenheit (4 degrees Celsius) warmer by their 71st birthday, according to the report, published Wednesday in the medical journal The Lancet. On any given day, a 7.2-degree difference might not sound like much, but as an average increase in temperature, it would be devastating for our health”. As another example, USA Today journalist Doyle Rice wrote, “The report stated that as temperatures rise, harvests will shrink – threatening food security and driving up food prices. Infants and small children are among the worst affected by malnutrition and related health problems such as stunted growth, weak immune systems, and long-term developmental problems. In addition, children will be especially susceptible to the infectious diseases that rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns will leave in their wake. 2018 was the second-most climatically suitable year on record for the spread of bacteria that cause much of diarrheal disease and wound infection around the world ... Extreme weather events will intensify into adulthood, the report found, with 152 out of 196 countries experiencing an increase in people exposed to wildfires since 2001-04, and a record 220 million more people over 65 exposed to heatwaves in 2018, when compared with 2000. For the world to meet its U.N. climate goals and protect the health of the next generation, the energy landscape will have to change drastically, and soon, the report warned. Nothing short of a 7.4% year-on-year cut in carbon dioxide emissions from 2019 to 2050 will limit global warming to the more ambitious goal of 2.7 degrees F”.

A gas flare at a Shell refinery in Norco, Louisiana. Photo: Drew Angerer/Getty Images. |

In late November, a new study from the UN found that greenhouse gas emissions reached record highs over the past year despite commitments and promises from UN member nations. The ‘UN Emissions Gap Report’ was released ahead of the planned UN climate talks in December. For example, New York Times journalist Somini Sengupta reported, “'The summary findings are bleak” said the annual assessment, which is produced by the United Nations Environment Program and is formally known as the Emissions Gap Report. Countries have failed to halt the rise of greenhouse gas emissions despite repeated warnings from scientists, with China and the United States, the two biggest polluters, further increasing their emissions last year. The result, the authors added, is that “deeper and faster cuts are now required”... Global greenhouse gas emissions have grown by 1.5 percent every year over the last decade, according to the annual assessment. The opposite must happen if the world is to avoid the worst effects of climate change, including more intense droughts, stronger storms and widespread hunger by midcentury. To stay within relatively safe limits, emissions must decline sharply, by 7.6 percent every year, between 2020 and 2030, the report warned”.

As we soon proceed into the year 2020, stay tuned for more descriptions and analyses of media trends in climate reporting through our ongoing MeCCO work.