Monthly Summaries

Issue 36, December 2019

[DOI]

A firefighter works to contain a bushfire near Bilpin, New South Wales. Photo: Mick Tsikas/EPA.

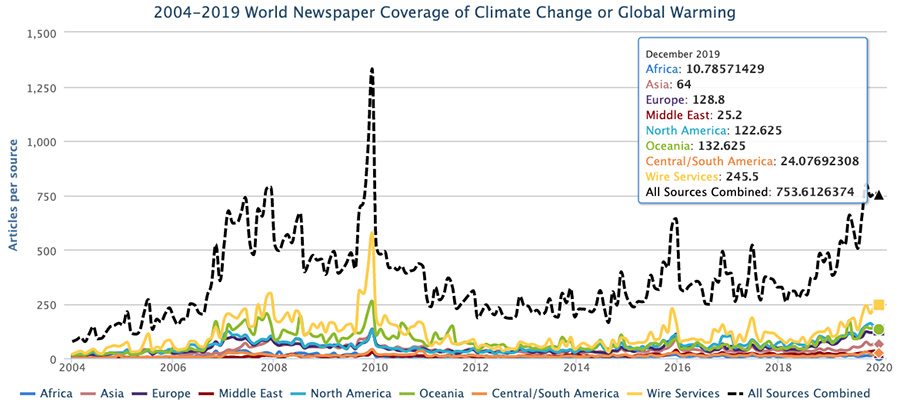

December media attention to climate change and global warming at the global level remained relatively steady from November 2019 coverage, up just under 1%. * However, news articles and segments about climate change and global warming was up 55% from a year earlier (December 2018). In particular, global radio coverage was up 19% from November 2019 and up 32% from December 2018.

Regionally, the ongoing stream of stories increased most in Europe (up 73%) and Central/South America (with coverage more than doubling). At the national-level, coverage notably continued to rise in Spain (up 72% from November).

Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through December 2019.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in one-hundred print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through December 2019.

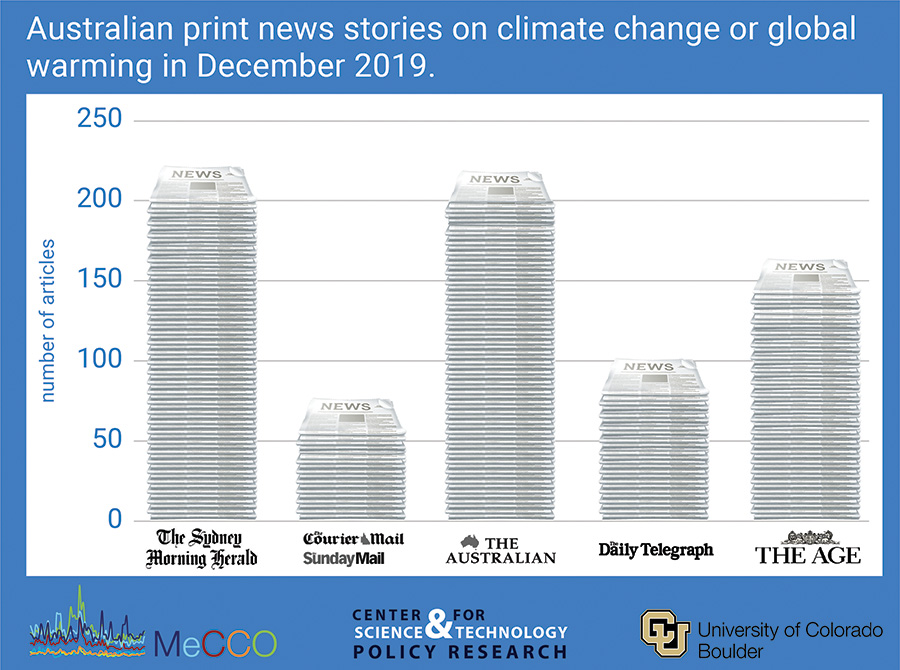

Many stories in Spanish media ran about the United Nations (UN) Madrid-based round of climate talks (COP25) that ran December 2-13. Focusing further at the country level, coverage in Japan was up 14% from November 2019 and double from a year prior (December 2018) while coverage in Sweden was up 36% from November 2019, and up 10% from the previous December. Meanwhile, coverage in Australia was up 1% in December from the previous month, yet up 48% from December 2018.

Figure 2 shows trends in print media coverage in Australia in December.

Figure 2. Number of news stories per outlet in December 2019 across the Australian newspapers The Sydney Morning Herald, Courier Mail & Sunday Mail, The Age, The Australian and The Daily Telegraph & Sunday Telegraph.

In December, ecological and meteorological connections with climate issues contributed substantially to media coverage of climate change around the world. To illustrate, continued coverage of extreme heat and bushfires in Australia sparked media attention to their links with planetary climate change. As domestic and international coverage focused on temperature records and fires in New South Wales, numerous journalists and outlets connected these dots with longer-term changes. For example, journalist Graham Readfern from The Guardian reported, “Australia recorded its hottest day on record on Wednesday, with an average maximum temperature of 41.9C (107.4F), beating the previous record by 1C that had been set only 24 hours earlier. Tuesday 16 December recorded an average of 40.9C across the continent, beating the previous record of 40.3C set on 7 January 2013. But it held the record for just 24 hours. Wednesday was even hotter across the country, with the highest maximum temperature reached in Birdsville, Queensland, which hit 47.7C (117.8). On Wednesday the lowest maximum was 19C at Low Head, Tasmania. On Thursday, Nullarbor in South Australia set the record for the hottest December day on record, recording 49.9C (121.8). Underlying these two major drivers of the heat is climate change – the simple physics of loading the atmosphere with extra greenhouse gases, mainly by burning fossil fuels. Australia’s latest State of the Climate report shows the country has warmed by just over 1C since 1910, leading to more extreme events. Watkins said: “That long-term warming sees the bar lifted up so that it’s easier to get extreme conditions now than it was 50 or 100 years ago,” “One part of me says that this is amazing but then another says that we have seen this in other parts of the world so we’re not especially surprised.” He pointed to France’s heatwave of June 2019, when Montpellier hit 43.5C, breaking its previous all-time heat record set in August 2017 by a huge 5.8C. “I’m not sure we are shocked by much any more.” Dr Sarah Perkins-Kirkpatrick, a climate scientist at the University of New South Wales specialising in extreme events, said climate change had given the natural drivers of Australia’s record -breaking heat “extra sting.” She said without the extra CO2 in the atmosphere “it would still have been warm”, but, she added: “I doubt very much we would have seen a record on Tuesday and then another one on Wednesday. And we are still at the beginning of the summer with a long way to go.” On Thursday, she was driving through thick smoke haze in north-west Sydney with her family. She said: “It is frightening and a little frustrating, but this is what climate scientists have been saying for decades. “I’m bordering on saying ‘I told you so’ but I don’t think anyone really wants to hear that”.

In December, media also covered ecological and meteorological aspects of climate change as they threaded through oceans-atmospheric interactions. For instance, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reporting of ocean acidification focused media attention. Journalist Rosanna Xia from The Los Angeles Times remarked, “Waters off the California coast are acidifying twice as fast as the global average, scientists found, threatening major fisheries and sounding the alarm that the ocean can absorb only so much more of the world’s carbon emissions. A new study led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration also made an unexpected connection between acidification and a climate cycle known as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation — the same shifting forces that other scientists say have a played a big role in the higher and faster rates of sea level rise hitting California in recent years. El Niño and La Niña cycles, researchers found, also add stress to these extreme changes in the ocean’s chemistry. These findings come at a time when record amounts of emissions have already exacerbated the stress on the marine environment. When carbon dioxide mixes with seawater, it undergoes chemical reactions that increase the water’s acidity. Across the globe, coral reefs are dying, oysters and clams are struggling to build their shells, and fish seem to be losing their sense of smell and direction. Harmful algal blooms are getting more toxic — and occurring more frequently. Researchers are barely keeping up with these new issues while still trying to understand what’s happening under the sea. Scientists call it the other major, but less talked about, CO2 problem. The ocean covers more than 70% of the Earth’s surface and has long been the unsung hero of climate change. It has absorbed more than a quarter of the carbon dioxide released by humans since the Industrial Revolution, and about 90% of the resulting heat — helping the air we breathe at the expense of a souring sea”. Concurrently, journalist Denise Chow from NBC News noted, “The waters off California are acidifying twice as rapidly as elsewhere on Earth, according to a study published Monday, which suggests that climate change is likely hastening and worsening chemical changes in the ocean that could threaten seafood and fisheries. Oceans play an important role in the planet's delicate carbon cycle, acting as a crucial reservoir that absorbs and stores carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. But the new research finds that although oceans can withstand some natural variations in climate, global warming may be adding to the stress on those ecosystems and overwhelming their ability to cope”.

California's kelp forests are in danger which is affecting the larger ocean ecosystem. Source: NBC News. |

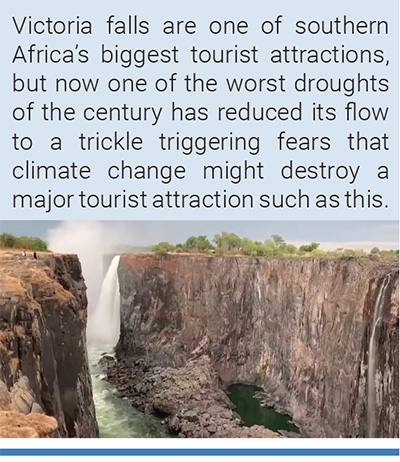

Moving from Oceania and North America to the African continent, ecological and meteorological-themed coverage of climate change pointed to the historic drying of Victoria Falls on the Zambezi River between Zambia and Zimbabwe. For example, journalist Mehr Gill from The Indian Express reported, “The flow of Victoria Falls, with a width of 1.7 km and a height of roughly 108 metres, has been reduced to a trickle due to the severe droughts in the southern African region since October 2018. The falls are fed by the Zambezi River and define the boundary between Zambia and Zimbabwe in southern Africa. The falls are one of southern Africa’s biggest tourist attractions, but now one of the worst droughts of the century has reduced its flow to a trickle triggering fears that climate change might destroy a major tourist attraction such as this. The news comes amid the ongoing 2019 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change that is being held in Madrid, Spain”.

In addition, some media coverage across Asia connected Typhoon Kammuri early in the month and Typhoon Phanfone later in December to patterns consistent with a changing climate. For example, Philippines correspondent Raul Dancel from The Straits Times reported, “Typhoon Kammuri slammed into the Philippines on Tuesday (Dec 3), bringing heavy rains and gale-force winds as it tore across the main island of Luzon. At least four people were killed and close to half-a-million huddled in evacuation centres as the typhoon, the 20th to hit the country this year, roared ashore late on Monday and passed south of the capital Manila, threatening to set off floods, landslides and storm surges… Typhoon season used to end in October but has stretched to December since the year 2000, a phenomenon experts blamed on climate change”.

Low-water levels are seen after a prolonged drought at Victoria Falls. Source: Guardian News https://youtu.be/glz64q1vaLs. |

In December, political and economic content also shaped media coverage. Prominently, media coverage of the United Nations (UN) climate negotiations in Madrid, Spain sparked coverage. For example, BBC journalist Matt McGrath reported, “Environmentalists and observers have been barred from UN climate talks in Madrid after a protest inside the conference. Around 200 climate campaigners were ejected after staging a sit in, preventing access to one of the negotiating halls. Protesters said they were "pushed, bullied and touched without consent." In the wake of the disruption all other observers were then barred from the talks. Observers play an important role in the talks, representing civil society. They are allowed to sit in on negotiations and have access to negotiators on condition that they do not reveal the contents of those discussions”. Concurrently, Associated Press reporters Arritz Parra and Frank Jordans noted, “With less than 72 hours left to reach a deal on key measures in the fight against global warming, major countries at a U.N. meeting on climate change took the floor to stake out their positions — showing that deep differences remain to be breached. In a sign of growing frustration over the pace of the talks in Madrid — the logo of which is a stylized ticking clock — more than 100 activists led by representatives of indigenous peoples from Latin and North America staged an impromptu protest, blocking the gates of the main plenary hall for a few tense minutes…Climate negotiators in Madrid also had one eye on Brussels, where the European Union announced a 100-billion euro ($130-billion) plan to help wean EU nations off fossil fuels. But some observers predicted the talks could head into overtime, with ministers struggling to agree on rules for a global carbon market and ways to compensate vulnerable countries for disasters caused by global warming. World leaders agreed in Paris four years ago to keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) — ideally no more than 1.5 C (2.7 F) — by the end of the century. Scientists say both of those goals will be missed by a wide margin unless drastic steps are taken to begin cutting greenhouse gas emissions next year”.

As the UN climate talks (COP25) came to a close with disappointing outcomes in mid-December, news focused on how the scale of international policy responses paled in comparison to the scale of ongoing climate challenges. For example, Wall Street Journal reporter Emre Peker dispatched, “Climate negotiators failed to strengthen targets to cut emissions or to create a global carbon-trading system, two main goals of the 2015 Paris accord, as the impending U.S. exit from the pact exacerbated challenges to cut record-high planet-warming gases. Delegates from nearly 200 nations sparred for two weeks in Madrid at the annual United Nations climate summit without setting new emissions targets before next year’s U.N. convention in Glasgow or creating a framework to reward and encourage efforts to cut emissions”. Meanwhile, Washington Post journalists Brady Dennis and Chico Harlan wrote, “Global climate talks lurched to an end here Sunday with finger-pointing, accusations of failure and fresh doubts about the world's collective resolve to slow the warming of the planet — at a moment when scientists say time is running out for people to avert steadily worsening climate disasters. After more than two weeks of negotiations, punctuated by raucous protests and constant reminders of a need to move faster, negotiators barely mustered enthusiasm for the compromise they had patched together, while raising grievances about the issues that remain unresolved. The negotiators failed to achieve their primary goals. Central among them: persuading the world’s largest carbon-emitting countries to pledge to tackle climate change more aggressively beginning in 2020”. Moreover, consistent BBC environment reporter Matt McGrath noted, “The longest United Nations climate talks on record have finally ended in Madrid with a compromise deal. Exhausted delegates reached agreement on the key question of increasing the global response to curbing carbon. All countries will need to put new climate pledges on the table by the time of the next major conference in Glasgow next year. Divisions over other questions - including carbon markets - were delayed until the next gathering”.

Chilean Environment Minister Carolina Schmidt, who chaired COP25, attends the closing session in Madrid. Marathon climate talks ended with negotiators postponing until next year a key decision on how to regulate global carbon markets. Photo: Bernat Armangue/AP. |

In December, scientific dimensions also grabbed some of the overall media attention to climate change and global warming. For example, reporting drew attention to findings from the Global Carbon Project that global greenhouse gases hit new record highs in 2019. New York Times journalist Brad Plumer wrote, “Emissions of planet-warming carbon dioxide from fossil fuels hit a record high in 2019, researchers said Tuesday, putting countries farther off course from their goal of halting global warming. The new data contained glimmers of good news: Worldwide, industrial emissions are on track to rise 0.6 percent this year, a considerably slower pace than the 1.5 percent increase seen in 2017 and the 2.1 percent rise in 2018. The United States and the European Union both managed to cut their carbon dioxide output this year, while India’s emissions grew far more slowly than expected. And global emissions from coal, the worst-polluting of all fossil fuels, unexpectedly declined by about 0.9 percent in 2019, although that drop was more than offset by strong growth in the use of oil and natural gas around the world. Scientists have long warned, however, that it’s not enough for emissions to grow slowly or even just stay flat in the years ahead. In order to avoid many of the most severe consequences of climate change — including deadlier heat waves, fiercer droughts, and food and water shortages — global carbon dioxide emissions would need to steadily decline each year and reach roughly zero well before the end of the century”. Meanwhile, journalists Fiona Harvey and Jennifer Rankin from The Guardian noted, “The rise in emissions was much smaller than in the last two years, but the continued increase means the world is still far from being on track to meet the goals of the Paris agreement on climate change, which would require emissions to peak then fall rapidly to reach net-zero by mid-century. Emissions for this year will be 4% higher than those in 2015, when the Paris agreement was signed. Governments are meeting this week and next in Madrid to hammer out some of the final details for implementing the Paris deal and start work on new commitments to cut emissions by 2030. But the new report shows the increasing difficulty of that task”.

|

Also, media coverage focused on new findings from NOAA's annual Arctic Report Card that warming in the Arctic has reached ‘unprecedented’ levels in December 2019. For example, in a PBS NewsHour segment with the topline ‘Arctic ecosystems and communities are increasingly at risk due to continued warming and declining sea ice’, journalist Nsikan Akpan observed, “Dead seals, marked with bald patches, washing onto shores or floating in rivers. A 900-mile-long bloom of algae stretching off the coast of Greenland, potentially suffocating wildlife. A giant, underground storehouse of carbon trapped in permafrost is leaking millions of tons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, heralding a feedback loop that will accelerate climate change in unpredictable ways. These are all bleak highlights from the 2019 Arctic Report Card, unveiled on Tuesday at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting. Published annually by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the 14th iteration of this peer-reviewed report examines the status of the planet’s northern expanse and changes due to global warming, with potential consequences reaching around the globe. In addition to scientific essays, this year’s report card for the first time delivers firsthand accounts from indigenous communities confronting the Arctic’s dramatic, climate-caused transformation. More than 70 such communities depend on Arctic ecosystems, which are warming twice as fast as any other location on the planet”. Meanwhile, New York Times journalist Kendra Pierre-Louis reported, “Temperatures in the Arctic region remained near record highs this year, according to a report issued on Tuesday, leading to low summer sea ice, cascading impacts on the regional food web and growing concerns over sea level rise. Average temperatures for the year ending in September were the second highest since 1900, the year records began, scientists said. While that fell short of a new high, it fit a worrying trend: Over all, the past six years have been the warmest ever recorded in the region”.

Finally, media accounts in December continued with a focus on cultural themes as well. From the start of the month, protests in Sydney Australia stretched from November (see November 2019 summary for more) to December as concerns about air quality and public health from bushfires provided news hooks for climate change stories. These also fueled demonstrations led by youth around the world as part of the ongoing ‘Fridays for Future’ movement. For example, journalists Arritz Parra and Frank Jordans from the Associated Press wrote, “Activists of all ages and from all corners of the planet demanded concrete action Friday against climate change from leaders and negotiators at a global summit in Madrid. The march was led by dozens of representatives of Latin America’s indigenous peoples – a mark of deference after anti-government protests in Chile, the original host of the summit, resulted in the talks suddenly being moved to Europe for the third year in a row…Organizers claimed 500,000 people turned out for the march, but authorities in Madrid put the number at 15,000 without an immediate explanation for the disparity in the count”.

2020 is here! As the next year and next decade unfolds, stay tuned for more descriptions and analyses of media trends in climate reporting through our ongoing MeCCO work.

* Due to data availability challenges through Nexis Uni for the ‘Globe & Mail’ in Canada in December 2019, we took the average number of stories January-November 2019 in place of December 2019 counts. We are working to update this count as soon as possible with the assistance of CU Libraries.