Monthly Summaries

Issue 72, December 2022

[DOI]

Melting ice on the Kuskokwim River on the Yukon Delta in Alaska. Scientists have found that Alaska has been warming twice as fast as the global average. Photo: Mark Ralston/AFP/Getty Images.

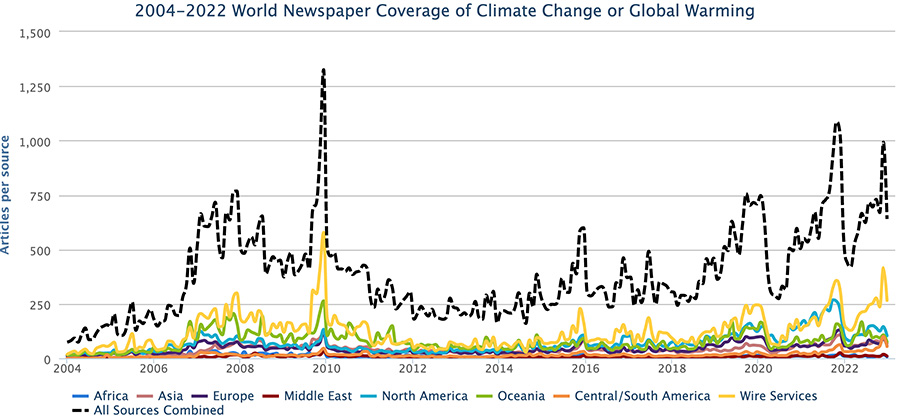

December media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe dropped 36% from November 2022 but remained 8% higher than December 2021 levels. International wire services similarly decreased 36%. Radio coverage also dipped 45% from November 2022. Compared to the previous month, coverage was pretty consistently down in all regions: North America (-29%), Asia (-30%), Oceania (-30%), the European Union (EU) (-40%), the Middle East (-45%), Latin America (-46%), and Africa (-56%). Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through December 2022.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through December 2022.

At the country level, United States (US) print coverage decreased 36% while television coverage also was down 45% from the previous month. Among other countries that we at the Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) monitor, coverage decreased across the board.

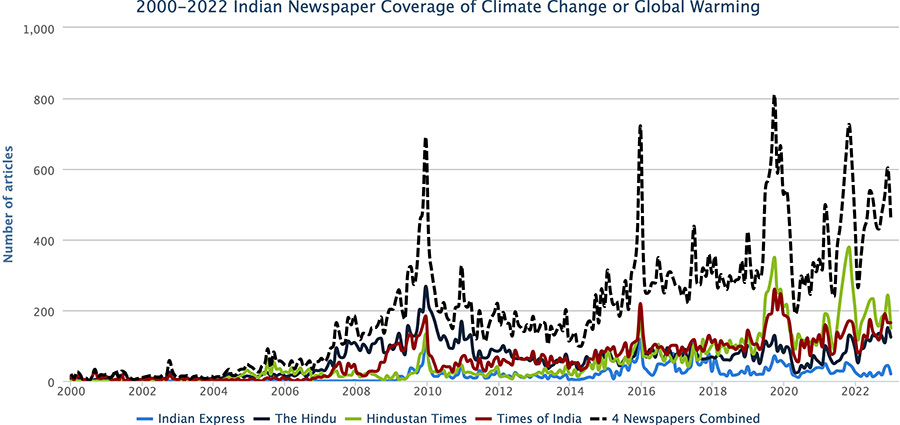

Figure 2. Newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming in Indian newspapers Indian Express, The Hindu, Hindustan Times, and Times of India from January 2004 through December 2022.

Turning to the content of coverage, media attention to climate change or global warming was punctuated with ecological and meteorological themes. For instance, El País journalist Victoria Torres Benayas noted, “Spain exceeds 15° on average for the first time in 2022, the warmest year in more than a century. The heat of 2022 is unprecedented in Spain. In the absence of nine days left until the end of December and which will register abnormally high temperatures, it has already become the warmest year for which there is data. "It is, with an overwhelming difference, the warmest year in the series, which starts in 1961. But highly reliable climate reconstructions allow us to affirm that it has been warmer for at least more than a century, since 1915," explains the Agency spokesperson. State Meteorology Department (Aemet) Rubén del Campo who, together with his counterpart Beatriz Hervella, makes a preliminary analysis of the year. For the first time, the country's average annual temperature will exceed 15˚ —for the moment 15.3˚— which is 1.6˚ above normal”.

Elsewhere, heavy rains in Kinshasa, Congo – with links made to climate change – populated several news accounts in December. For example, New York Times correspondent Elian Peltier noted, “At least 141 people died in the Democratic Republic of Congo on Tuesday after heavy rains caused floods and landslides in the capital, Kinshasa, Congolese officials said. It was the latest in a series of deadly environmental disasters to hit West and Central African countries this year. Many neighborhoods, major infrastructure and key roads were still underwater or in ruins on Wednesday after the previous day’s all-night downpour brought the worst floods in years to the city of 15 million people. Nearly 40,000 households were flooded and 280 collapsed, according to an official document seen by The New York Times. President Félix Tshisekedi, who is in Washington for a U.S.-Africa summit, declared three days of mourning and said he would cut his trip short, flying back to Kinshasa on Thursday after meeting with President Biden. West and Central Africa have suffered from devastating floods this year, highlighting a deadly mix of chaotic urban development and climate change faced by dozens of fast-growing African cities. In Chad, the worst floods in decades displaced thousands in September and left the capital, Ndjamena, navigable only by boat. In Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, hundreds of people died, a million were displaced and at least 200,000 houses were destroyed in November after the nation’s worst flooding in a decade. Scientists said in a report last month that the rainy season, which runs from April to November, had been 20 percent wetter than it would have been without climate change”.

Also, cold weather across North America at the end of December generated several news accounts that connected to changes in the climate. For example, New York Times reporter Henry Fountain wrote, “The winter storm that ravaged much of the United States and Canada through Christmas was expected to be bad, and it was. Forecasters billed it as a “once in a generation” event even before ice began coating the steep streets of Seattle, white-out conditions spread from the Plains to the Midwest and more than four feet of snow was dumped on Buffalo in a storm that killed more than two dozen people. The links between climate change and much extreme weather are becoming increasingly clear. In a warming planet, heat waves are hotter, droughts are prolonged, summer downpours are more severe”.

Figure 3. Newspaper front pages stories in December with links to climate change and climate risks.

December media coverage also featured various cultural stories relating to climate change or global warming were evident in wider news coverage of climate change or global warming. To illustrate, new findings regarding school textbooks found that there remains only scant attention paid to climate change in typical science textbooks. News media focused on this. For example, Washington Post journalist Caroline Preston reported, “Evidence is mounting fast of the devastating consequences of climate change on the planet, but college textbooks are not keeping up. A study released Wednesday found that most college biology textbooks published in the 2010s had less content on climate change than textbooks from the previous decade and gave shrinking attention to possible solutions to the global crisis”.

Activists protest fossil fuels as part of Earth Day activities on April 22, 2022. Photo: Michael Reynolds/EPA. |

Many scientific themes continued to emerge in media stories during the month of December through new studies, reports, and assessments. One such report was the annual ‘Arctic Report Card’ published by researchers at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Stories about report findings dotted the media landscape around the world, particularly in temperate zones. For example, Washington Post correspondent Kasha Patel wrote, “The bison couldn’t crack the ice. As Christmastime wound down last year, unseasonably warm temperatures and heavy rain in Alaska’s Delta Junction melted snow and ice, which quickly refroze due to subzero temperatures near the surface. Usually, the bovine can shovel through snow with their heads and horns, but the frozen snow and ice persisted like a layer of cement atop the grasses and plants they need to feed on. And the bison couldn’t get through. About 180 bison, or a third of the Delta herd, starved to death. Those that survived were skinny and in poor form. Bison season in the Delta Junction area, one of the most popular hunting seasons in Alaska, was cut short from six months to two weeks. It was one of several exceptional events the Arctic experienced over the past year, all intensified by a warmer world. A typhoon, formed in unusually warm waters in the North Pacific, hit the western coast of Alaska as the state’s strongest storm in decades. A late heat wave in Greenland caused unprecedented melt in September, which can contribute to sea level rise. Despite decent winter snow in Alaska, the rapid onset of summer created devastating conditions for wildfires that burned a record million acres by June. The recent events are a continuation of a decades-long destabilization in the Arctic region, researchers said in the 2022 Arctic Report Card”.

Last, many political and economic themed media stories about climate change or global warming continued to roll out in the month of December. At the start of the month, documents released by the US House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform revealed that rhetoric and action was quite divergent from top officials in major oil companies such as Shell, Chevron, Exxon, and BP. For example, CNN correspondent René Marsh reported, “Big Oil companies have engaged in a “long-running greenwashing campaign” while raking in “record profits at the expense of American consumers,” the Democratic-led House Oversight Committee has found after a year-long investigation into climate disinformation from the fossil fuel industry. The committee found the fossil fuel industry is “posturing on climate issues while avoiding real commitments” to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Lawmakers said it has sought to portray itself as part of the climate solution, even as internal industry documents reveal how companies have avoided making real commitments”. Meanwhile, Guardian journalist Oliver Milman wrote, “Some of the world’s largest oil and gas companies have internally dismissed the need to swiftly move to renewable energy and cut planet-heating emissions, despite publicly portraying themselves as concerned about the climate crisis, a US House of Representatives committee has found. Documents obtained from companies including Exxon, Shell, BP and Chevron show that the fossil fuel industry “has no real plans to clean up its act and is barreling ahead with plans to pump more dirty fuels for decades to come”, said Carolyn Maloney, the chair of the House oversight committee, which has investigated the sector for the past year. The committee accused the oil firms of a “long-running greenwashing campaign” by committing to major new projects to extract and burn fossil fuels despite espousing their efforts to go green. In reality, executives, the documents show, were derisive of the need to cut emissions, disparaged climate activists and worked to secure US government tax credits for carbon capture projects that would allow them to continue business as usual”.

The dry bed of the Gan River, in China's Jiangxi province. Photo: Thomas Peter/Reuters. |

Also in the political sphere, ongoing stories of the Russian invasion of Ukraine – with consequent impacts on energy supplies and policy – proliferated, particularly in Europe. For example, La Vanguardia journalist Piergiorgio M. Sandri noted, “World coal consumption marks a new record due to the energy crisis. War fuels a cheap resource but a major emitter of carbon dioxide. Never before has so much coal been consumed and produced in the world. At a time when the fight against climate change forces us to reconsider the energy supply towards less polluting sources, the facts say that one of the resources responsible for the most emissions not only refuses to die, but is booming and in top form . This is stated in the report published yesterday by the International Energy Agency (IEA). High gas prices after Russia's invasion of Ukraine and consequent supply disruptions (particularly from Russia) have led some countries to turn to relatively cheaper coal this year, albeit the biggest source of carbon dioxide emissions. of the world energy system”.

Meanwhile in related economics news, British NGO Christian Aid published a list of the 10 costliest 2022 weather disasters. This grabbed European media attention as well. For instance, El País journalist Manuel Planelles noted, “The economic impact of these ten events linked to the climate crisis calculated in the study of this organization exceeds 168.100 million dollars. But the authors caution that most of their estimates are based only on losses covered by insurers, so it is very likely that "the true financial costs are even higher, while the human costs are often not accounted for", warns the NGO”.

Thanks for your interest in our Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) work monitoring media coverage of these intersecting dimensions and themes associated with climate change and global warming.

- report prepared by Max Boykoff, Presley Church, Rogelio Fernández-Reyes, Jennifer Katzung, Ami Nacu-Schmidt and Olivia Pearman