Last week’s Economist provided a characterization of debates over climate change as being “alarmingly prone to zealotry and taboos.” One such taboo surrounds observations that the dominant policy approach is bankrupt, which evokes a squeamish reaction among many.

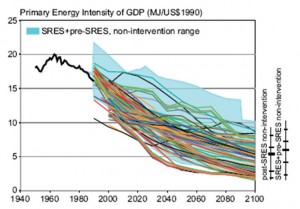

In a paper just out in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A (PDF) Kevin Anderson and Alice Bows disregard taboos and squeamishness and observe that the current approach to mitigation policies focused on specific targets and timetables (i.e., 2 degrees, 450 ppm) does “not, in isolation, have a scientific basis and are likely to lead to dangerously misguided policies .” (Many thanks to HD for the pointer.) This provocative paper ends by suggesting that “it is difficult to envisage anything other than a planned economic recession being compatible with stabilization at or below 650 ppmv CO2e.”

The squeamish will say not to talk about such things, and the analysis by Anderson and Bows ultimately may not stand up to close scrutiny (though its analysis is quite consistent with Pielke, Wigley, and Green’s “Dangerous Assumptions”). On the other hand, others will laugh at the notion of “planned economic recession” and say we should just give up the idea of decarbonization. Both reactions would be wrong — the continuing comprehensive failure of mitigation policies, and its consequences, should be the subject of serious discussion, especially the introduction of radically new options beyond those that have yielded little progress over the past few decades.

Here is an excerpt from the paper, but do read the whole analysis for the basis for the following conclusions:

It is increasingly unlikely that an early and explicit global climate change agreement or collective ad hoc national mitigation policies will deliver the urgent and dramatic reversal in emission trends necessary for stabilization at 450 ppmv CO2e. Similarly, the mainstream climate change agenda is far removed from the rates of mitigation necessary to stabilize at 550 ppmv CO2e. Given the

reluctance, at virtually all levels, to openly engage with the unprecedented scale of both current emissions and their associated growth rates, even an optimistic interpretation of the current framing of climate change implies that stabilization much below 650 ppmv CO2e is improbable.

The analysis presented within this paper suggests that the rhetoric of 2 C is subverting a meaningful, open and empirically informed dialogue on climate change. While it may be argued that 2 C provides a reasonable guide to the appropriate scale of mitigation, it is a dangerously misleading basis for informing the adaptation agenda. In the absence of an almost immediate step change in mitigation (away from the current trend of 3% annual emission growth), adaptation would be much better guided by stabilization at 650 ppmv CO2e (i.e. approx. 4 C).14 However, even this level of stabilization assumes rapid success in curtailing deforestation, an early reversal of current trends in non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions and urgent decarbonization of the global energy system.

Finally, the quantitative conclusions developed here are based on a global analysis. If, during the next two decades, transition economies, such as China, India and Brazil, and newly industrializing nations across Africa and elsewhere are not to have their economic growth stifled, their emissions of CO2e will

inevitably rise. Given any meaningful global emission caps, the implications of this for the industrialized nations are bleak. Even atmospheric stabilization at 650 ppmv CO2e demands the majority of OECD nations begin to make draconian emission reductions within a decade. Such a situation is unprecedented for economically prosperous nations. Unless economic growth can be reconciled with unprecedented rates of decarbonization (in excess of 6% per year15), it is difficult to envisage anything other than a planned economic recession being compatible with stabilization at or below 650 ppmv CO2e.

Ultimately, the latest scientific understanding of climate change allied with current emission trends and a commitment to ‘limiting average global temperature increases to below 4 C above pre-industrial levels’, demands a radical reframing16 of both the climate change agenda, and the economic characterization of contemporary society.