Technocracy versus Democratic Control

February 11th, 2008Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

In a recent commentary (PDF) NASA’s James Hansen has called for reform in how the government treats scientists, and the creation of special rules for how government scientists communicate with Congress and the public. Hansen’s commentary raises important general questions about democratic governance and the role of scientists in government. Should government scientists somehow be exempt from democratic accountability? Especially on a subject as important as climate change, where (in the words of Jim Hansen) the future of the planet is at stake?

Hansen recommends that presidential candidates be asked the following:

Do you pledge, if elected, to allow government scientists to communicate scientific results without political interference by (1) having Public Affairs Offices of science agencies headed by career professionals with civil service protections, and (2) terminating the practice of White House OMB filtering testimony by government scientists to Congress?

Hansen does not like the political control of government communications, regardless of who has been elected into power:

The Public Affairs Offices (PAOs) of science agencies have become mouthpieces for the Administration in power. This, too, is a bi-partisan problem. Top people in the Headquarters Offices of Public Affairs can and often are thrown out in a heart-beat when an election changes the party in control of the Executive Branch. The Executive Branch has learned that the PAOs can be effective political instruments and, with some success, they are attempting to turn them into Offices of Propaganda, masters of double-speak (“clean coal”, “clear skies”, “healthy forests”…) that would make Orwell envious. Again it is a bi-partisan problem, the control of PAOs being exercised by top political appointees who are replaced rapidly with a change of administration. It is these political appointees that are the problem – the career civil servants at the NASA Centers, e.g., are professionals of high integrity, as are most people at Headquarters.

The solution, in Hansen’s view, is to take power away from politically appointed officials and place it into the hands of the career civil service – not a surprising view coming from a career civil servant. Hugh Heclo, a famous scholar of the federal bureaucracy, has written in some depth on the complex tensions between political officials and bureaucrats, and recognizes that there are no easy answers. But he does recognize that bureaucracies cannot be allowed free reign in democracies. He writes in his classic book A Government of Strangers (1977, The Brookings Institution):

If democracy is to work, political representatives must not only be formally installed in government posts but must in some sense gain control of large-scale bureaucracies that constitute the modern state. (p. 4)

A commitment to the orderly transition of governmental control via elections necessarily means that those in charge will change (p. 109):

Any commitment to democratic values necessarily means accepting a measure of instability in the top governing levels.

With his proposal to empower civil service scientists and their colleagues, Hansen seeks to wrest control away from democratically elected governments. This form of government is called technocracy and can be a form of authoritarian rule. Hansen recognizes this point when he writes,

“Politicians do not give up instruments of political power AFTER an election that they have won, unless they made an unambiguous promise before the election.”

While, as Hugh Heclo observes the appropriate balance of control between political officials and bureaucrats is worth some discussion, it seems rather odd to suggest that democratic governance will be better served by empowering technocrats who are largely unaccountable to the public. Let us imagine what might have happened if rather than a political appointee of the Bush Administration who had refused James Hansen’s request to be interviewed by the media, it was instead a career civil servant. One might argue that the very fact that it was a political appointee hastened that individual’s loss of his job when Jim Hansen complained publicly about the Administration’s efforts to manage his ability to speak to the media. Had that person been a career civil servant removing him from that position would have been immeasurably more difficult, due to the career protections offered to civil servants. Democratic accountability is enhanced when there are clear lines of responsibility. In the case of Jim Hansen’s complaints, it was obvious that the Bush Administration’s ham-handed efforts to keep him from speaking were politically motivated and indefensible. Hence, the system worked as it should have and in the end accountability was served.

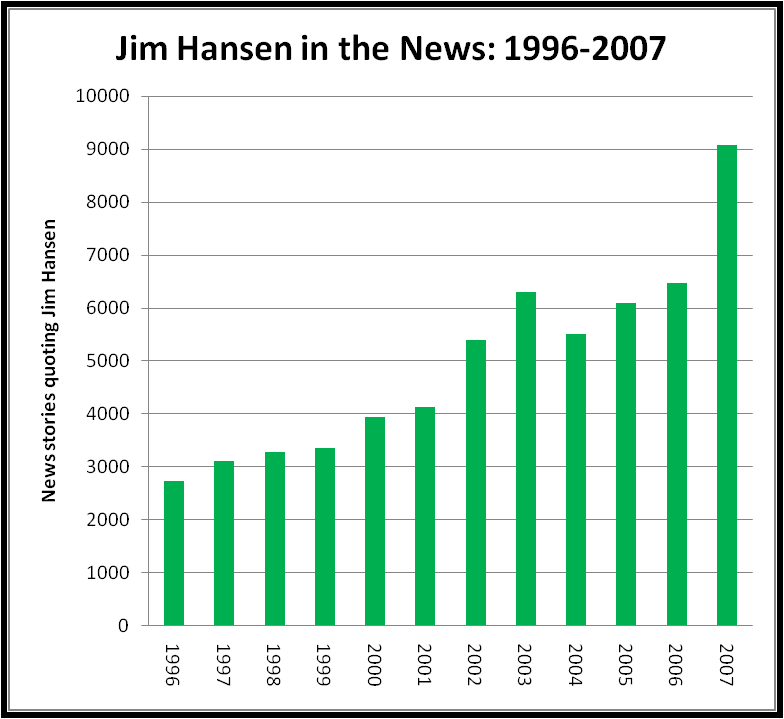

As an indication of the “success” (cough, cough) of the Bush Administration’s efforts to manage Jim Hansen’s media appearances, consider the following graph (produced from data gathered on Google News) which shows the number of news stories that mentioned James Hansen from 1996-2007. In 2007 Jim Hansen appeared in an average of 25 news stories per day for the entire year! If the Bush Administration was trying to muzzle Jim Hansen, then they failed miserably (which given their track record in a range of areas is probably not surprising).

Jim Hansen also complains about the coordination of testimony (which includes editing) given by government officials to Congress by the Office of Management and Budget, which resides in the Executive Office of the President. Hansen thinks that government scientists should be exempt from such administrative oversight.

OMB’s editing of the scientific content is invariably designed to make the testimony fit better with the position of the political party in power (yes, it is a bi-partisan problem). Where is it stated or implied in the Constitution that the Executive Branch should have such authority?

While it seems fairly obvious that government officials have an obligation to support the elected officials for whom they work, the specific answer to Hansen’s question can be found in Section 22 of OMB Circular A-11 (PDF), which discusses agency communications with Congress. It says that once the President transmits to Congress his budget — which represents the Administration’s priorities and policies — a number of ground rules govern communication with Congress, among them a requirement that the testimony be reviewed by OMB for conformance to Administration policies. It states:

Witnesses will avoid volunteering personal opinions that reflect positions inconsistent with the President’s program or appropriation request.

Now what if the president’s official policy for Program X is justified based on the “fact” that 2 + 2 = 5. Does the testifying official have to accept that 2 + 2 = 5 if asked by a member of Congress whether s/he in fact believes that 2 + 2 = 5? No, of course not. They can say the 2 + 2 = 4, and perhaps this will get them in the news for saying something at odds with the Administration, as recently happened when a State Department official contradicted official government policy on North Korea. The government official – whether civil servant or political appointee — then accepts the consequences of his or her actions, and ultimately, if they feel that they cannot support the government, then they always have the option of resigning. As political scientist J. D. Sobel writes:

All senior leaders, whether appointed or career, serve in an administration and for a principal with broader responsibilities. These officials have special obligations to protect and support their principal and administration as the mechanism of democratic accountability in government. They have strong implicit obligations to stay within the policy framework of their administration and not undermine their principal.

Jim Hansen argues that “trying to make government science submit to political command and control, is a threat to our democracy, and, as a result, a threat to the planet.” I have a different view. Those who would argue that government scientists are somehow exempt from democratic accountability are the real threat to democracy, and encourage technocratic decision making if not outright authoritarianism. Democracy and science are compatible, and so too is democracy and effective action on climate change.

If Jim Hansen can’t support the officials of the United States who are elected by the people and for whom he works and takes a paycheck, then he might consider another line of work. University professors can say all sorts of things, and even testify before Congress. Many advocacy groups would jump at an opportunity to have him on their staff, and I have no doubt that his Congressional appearances would continue. And of course, he could always run for office. But should we redesign the government to give more power to experts at the expense of democratic accountability? I don’t think so.

February 11th, 2008 at 1:35 pm

Let me suggest that the control Hansen wants is on the same slope occupied by the climate science book Roger wrote about last month. In that case, they argued for an authoritarian government. A necessary consequence of democracy is the capacity to choose badly.

February 12th, 2008 at 6:04 am

Jim Hansen is rightly concerned with a particular kind of administrative interference: the blocking of the dissemination of scientific findings that an administration finds politically inconvenient.

Except for the VERY rare scientific fact that might somehow endanger “national security”, censorship of ANY other ‘facts’ (for example, about global warming) should not be subject to political censorship!

He’s not looking for freedom from review, or even the right to publicly criticize his bosses; only freedom from censorship of research findings.

His questions are designed to elicit responses that would indicate how candidates view this important question.

February 12th, 2008 at 9:18 am

Hi,

Len, Dr. Hansen works for the government. The administration appoints the heads of these offices. We pay for these offices. We elect the people who appoint the heads of office and how to distribute the money. The appointees report to the administration and is accountable to the administration who we elect. Now put a Government employee who’s pay and accountability is to him/her self. If you do not like the current administration then vote. Thank you Roger for an honest thread. “A government powerful enough to provide everything is powerful enough to take it all away”. Thomas Jefferson.

February 12th, 2008 at 12:16 pm

Nice post.

It’s important to realize that when politicians hire scientists they will play politics with science. I don’t think that there is any practical way to avoid it except avoid having government hire scientists.

There is no shortage of independent research being done, I guess I have a hard time understanding what Hansen’s complaint really is.

February 12th, 2008 at 12:18 pm

Nice post.

It’s important to realize that when politicians hire scientists they will play politics with science. I don’t think that there is any practical way to avoid it except avoid having government hire scientists.

There is no shortage of independent research being done, I guess I have a hard time understanding what Hansen’s complaint really is.

February 12th, 2008 at 12:26 pm

Jim:

‘We’ pay for the research that these government employees perform, usually in the context of long-term programs originally established by bi-partisan Congressional action. Therefore, it normally should be unlawful (as in the Freedom of Information Act), for an administration to act to withhold the results of such research from the public – when it’s because those results conflict with the administration’s political agenda.

February 13th, 2008 at 6:16 am

This comments sent in by email from 2 researchers at NASA GISS, one a former student of mine!

“Dear Roger,

Interesting plot on your prometheus blog. I wanted to make a comment

if possible (it doesn’t seem to let me sign on even after creating an

account).

After looking at your graph, I wondered if the increased frequency of

Hansen citations in google news is relevant. Over lunch break, Erik

and I discovered a few things:

(1) It seems you got your data by googling James Hansen, with no

quotes, thus overestimating how much the particular James Hansen of

interest is quoted in the news. I can get the exact same numbers as in your

graph that way — for example, 2740 in 1996 and 9040 in 2007.

However, it seems like a lot of articles that appear using this

search term are not related to James E. Hansen of NASA GISS. For

example, many are about a Republican in Utah, or other deceased

people named James Smith or Steve Hansen. After trying: James Hansen

NASA, “James Hansen”, “James E. Hansen”, “James Hansen” “climate

change”, I think that the search term with the highest relevant yield

is simply: James Hansen NASA. Using this, he gets only 37 articles

in 1996 and 1080 in 2007. That’s not quite the 25 articles a day

being claimed. Still, that’s a big increase, but on to the next point.

(2) I also searched for: climate change. If you then normalize

the number of citations for James Hansen NASA by the number for

climate change, you don’t see any increasing trend over 1996-2007.

Maybe that’s not necessarily the best way to normalize, but the point

is that while there are x100 more references to Hansen now than in

1996 there are also x100 more references to climate change, I.P.C.C.,

etc. It’s just a hotter topic now (ha ha ha).

The prometheus plot does not reveal anything about trends in administrative

interference with public statements by civil servants.

Daven Henze and Erik Noble”

RESPONSE:

Thanks guys. I assume that non-NASA “James Hansen” mentions will be more or less random, and your point 1 seems to confirm this.

On your conclusion: “The prometheus plot does not reveal anything about trends in administrative

interference with public statements by civil servants.” — This is indeed what the graph shows.

February 13th, 2008 at 3:56 pm

Received by email from Sylvain Allard:

“Like on many other subject I don’t share the point of view of James Hansen that civil servant impede is ability to convey his message that the future of the planet his at risk.

1) I believe that his opinion is well known to anyone who has even a very limited knowledge about the subject of climate change.

2) I would like to know if he support the same right to other public scientist that don’t consider that the planet is at risk. I mean if we consider that he refused to appear in a congress commity (I believe it was the one where the Wegman report got released) because he didn’t like some of the invited scientist.

3) If he doesn’t like the direction the government imposes on the organisation he is working with then he is free to do what he consider to be the right thing. How many scientist have resigned from the IPCC because they didn’t like the political direction the process took.

James Hansen is politically and openly affiliated to the democrat. He openly discuss that strong action should be taken to mitigate CO2. It would be about time for him to decide if his action or desire wouldn’t be better served if he was part of a lobbying group than as a civil scientist.”

February 14th, 2008 at 4:54 am

Sylvain:

You are mistaken about Jim Hansen. Until rather recently, he has been quite politically conservative. And I believe still is, on other than climate issues.

What Hansen is concerned about, in the article Roger has chosen to criticize, stems from his concern that “Efforts to shield expert research and decision making from public scrutiny and accountability invariably backfire, fueling distrust and counter-productive decisions” – especially those “counter-productive decisions”.

But this quote is not Hansen’s, but Roger Pielke’s (in his Prediction for Decision)

February 14th, 2008 at 1:02 pm

This is very difficult constitutional stuff. Rather than involving ourselves in this potential quagmire, what about closing our inhouse science agencies (other than ones that appear not to have this problem, such as ARS) and giving all the funds freed up in competitive grants to universities to examine the same problems? Then there would be no potential conflict of interest. I bet the universities would find this an intriguing concept, rife with possibilities.

Sharon Friedman

February 25th, 2008 at 5:04 pm

Technocracy is a form of authoritarian rule or government which seeks to wrest control away from democratically elected governments and maintains a perfect balance of control between political officials and bureaucrats. Thus it empowers civil service scientists and their colleagues.

http://www.keyman.uk.com

February 25th, 2008 at 5:08 pm

Technocracy is a form of authoritarian rule or government which seeks to wrest control away from democratically elected governments and maintains a perfect balance of control between political officials and bureaucrats. Thus it empowers civil service scientists and their colleagues.

http://www.keyman.uk.com