Draft CCSP Synthesis Report

July 28th, 2008Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

The U.S. Climate Change Science Program has put online for public comment a draft version of its synthesis report ( here in PDF), and I suppose the good news is that it is a draft, which means that it is subject to revision. But what the draft includes is troubling in several respects.

First, the report adopts an approach to presenting the science more befitting an advocacy group, rather than a interagency science assessment. The report ignores the actual literature on economics and policy, choosing instead to present fluffy exhortations about the urgency of action and reducing emissions. I can get that level of policy discussion from any garden variety NGO, for $2 billion per year over the past 18 years, I would expect a bit more.

The report opens with this language:

The Future is in Our Hands

Human-induced climate change is affecting us now. Its impacts on our economy, security, and quality of life will increase in the decades to come. Beyond the next few decades, when warming is “locked in” to the climate system from human activities to date, the future lies largely in our hands. Will we begin reducing heat-trapping emissions now, thereby reducing future climate disruption and its impacts? Will we alter our planning and development in ways that reduce our vulnerability to the changes that are already on the way? The choices are ours.

Pretty thin stuff. The report speaks of urgency:

Once considered a problem mainly for the future, climate change is now upon us. People are at the heart of this problem: we are causing it, and we are being affected by it. The rapid onset of many aspects of climate change highlights the urgency of confronting this challenge without further delay. The choices that we make now will influence current and future emissions of heat-trapping gases, and can help to reduce future warming.

It is not within the Congressional mandate of the CCSP to tell policymakers when to act or what goals to pursue. The report does have some limited discussion of options, which would be great (and within the mandate) if it were comprehensive and scientifically rigorous. Unfortunately, it is neither.

Despite recognizing that some adaptation will be necessary, and discussing adaptive responses in the text, the report has a strong bias against adaptation in favor of mitigation:

The more we mitigate (reduce emissions), the less climate change we’ll experience and the less severe the impacts will be, and thus, the less adaptation will be required. . . Despite what is widely assumed to be the considerable adaptive capacity of the United States, we have not always succeeded in avoiding significant losses and disruptions, for example, due to extreme weather events. There are many challenges and limits to adaptation. Some adaptations will be very expensive. We will be adapting to a moving target, as future climate will not be stationary but continually changing. And if emissions and thus warming are at the high end of future scenarios, some changes will be so large that adaptation is unlikely to be successful.

A large body of work, some of which I’ve contributed, indicates that adaptation and mitigation are not tradeoffs, but complements. Somehow this literature escaped the thorough review done by the authors of this report.

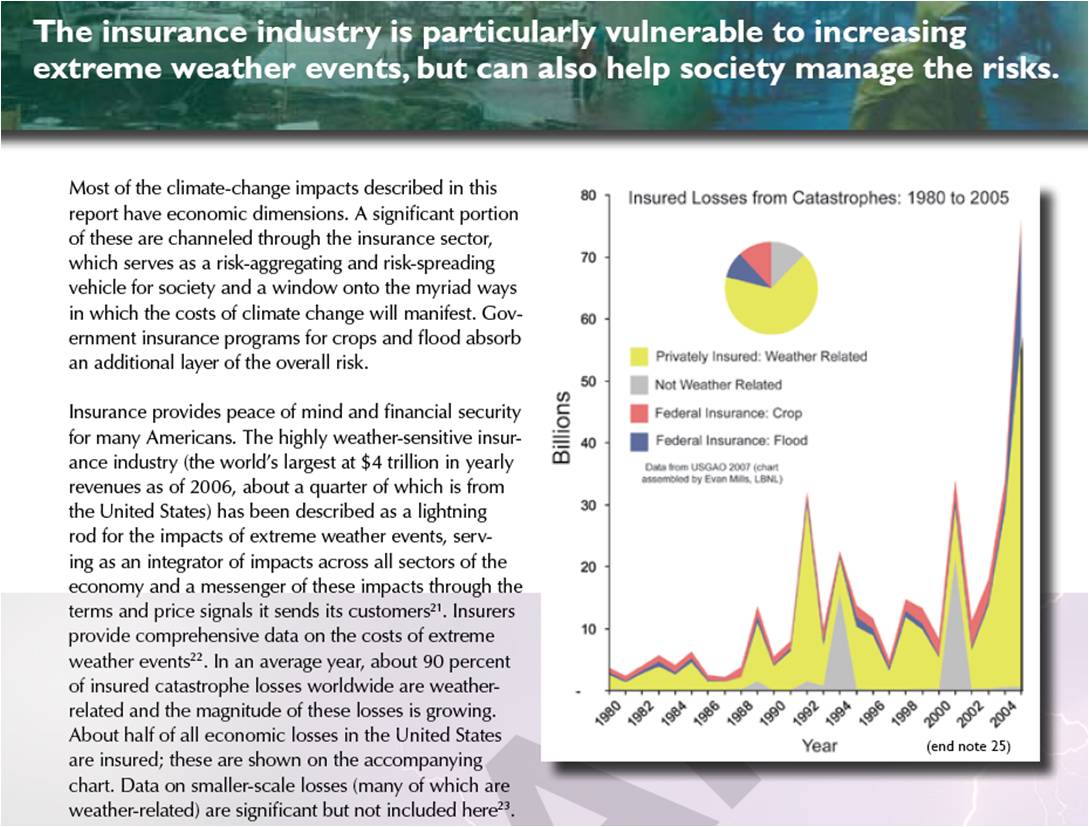

The report claims to be focused on bringing together the “best available science.” However in the area of my expertise, disasters and climate change, the report is an embarrassment. For example, once again, it uses the economic costs of disasters as evidence of climate change and its impacts, as shown in the following figure from the report.

Then, later in the report it discusses increasing U.S. precipitation under the heading “Floods” and next to a picture of a flooded house (below). However, in the U.S. there has been no increase in streamflow and flood damage has decreased dramatically as a fraction of GDP. Thus the report reflects ignorance on this subject or is willfully misleading. Neither prospect gives one much confidence in a government science report.

In short, in areas where I have expertise, at best the reporting of the science of climate impacts in this report is highly selective. Less generously it is misleading, incorrect, and a poor reflection on the government scientists whose names appear on the title page, many of whom I know and have respect for. The report asks for comments during the next few weeks, and I will submit some reactions, which I’ll also post here.

So why does the report have such an advocacy focus and rely on misleading arguments?

One answer is to have a look to the people chiefly responsible for the editing of the report, and also the section on natural disasters, where one person’s views are reported almost exclusively to any others.

Perhaps it is time to rotate control of U.S. government “science” reports to some new faces?

July 29th, 2008 at 4:09 am

Roger, it seems to me that the draft synthesis focusses on describing ongoing and expected impacts from climate change and areas where adapation is needed, with only limited initial attention being given to mitigation. Adaptation gets much more attention than mitigation, so I fail to see your point that there is a strong bias in favor of mitigation.

On flooding, are the below figures they used wrong, or do you just want more nuance about how an increasingly wealthy society can better handle greater flooding risks?

“Heavy downpours have increased in recent decades and are projected to increase further as the world continues to warm. In the U.S., the amount of precipitation falling in the heaviest 1 percent of rain events increased by 20 percent in the past century, while total precipitation increased by 7 percent. Over the last century, there was a 50 percent increase in the frequency of days with precipitation over four inches in the upper Midwest. Other regions, notably the South, have also seen strong increases in heavy downpours, with most of these coming in the warm season and almost all of the increase coming in the last few decades.”

July 29th, 2008 at 6:00 am

Tom-

Imagine that this report was about the Iraqi threat and was written in 2002. Further, imagine a section titled: WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION

The text underneath says something like:

“Iraq ordered aluminum tubes with a diameter of 75 mm and built to exacting specifications at a European factory. . . . Such tubes may be used in uranium enrichment.”

The image next to the text shows a nuclear explosion.

One might complain that there is actually no evidence of WMDs presented in the paragraph and the presence of aluminum tubes might be consistent with a WMD program, but hardly definitive, especially because you are aware of evidence to the contrary not cited in the discussion.

The discussion of floods is highly misleading in exactly this same way.

July 29th, 2008 at 10:32 am

TokyoTim,

In a paper we published in in 2004 (Michaels et al. 2004, Int. J. Climatol.) we examined the precipitation changes on the wettest days of the year (across the U.S.) and found that while the total precipitation falling on the wettest days of the year was increasing, it was not increasing faster than the total precipitation. Thus, generally, there was no disproportionate increase in extreme precipitation events. This seems to contradict the CCSP statement you quoted.

I can’t seem to find our reference in the new CCSP report. Perhaps I’ve overlooked it.

-Chip Knappenberger

July 29th, 2008 at 8:01 pm

Hi,

Roger, I think that “flooded house” is actually a “‘flooded’ house”.

I think the flooding is fake. Look at the .pdf blown up to 800 percent or more. You’ll see that the pixelation for the water is different than the pixelation for the house.

I’m not an expert on the subject, but I think it’s faked.

Mark

P.S. I’d be interested in the opinions of others…especially people who consider themselves to have expertise in such matters.

July 29th, 2008 at 9:18 pm

Is it just me or they are using many graph that are outdated:

1) Global temp that using sea surface temp even though they should know that they need to be adjusted post-1940. I know it is not the same graph than the met office but it seems to me that they use the same sst data.

2) They seem to use the disqualified Hockey stick for the last 1000 years, the LIA is not evident to find.

3) The US temp graph seems to disregard the Hansen Y2K error although the graph can be form another sources.

Also there is no margin anywhere. In the 1000 years reconstruction they don’t even mention that the farther in they they go the more uncertain the data is.

This is the kind of report one would expect from the WWF not from a National organization.

Mark, it maybe a problem with your monitor. It must be easy enough to find a recent photo of a flooded house, what ever was the cause of it.

July 29th, 2008 at 11:08 pm

Roger, perhaps you could respond to my two points:

- contrary to your complaint, the report clearly emphasizes adaptation over mitigation; and

- are the figures on flooding that they present wrong, or do you simply want additional nuance and discussion added?

I have a hard time following your inflammatory Iraq/nukes analogy since I cannot see what information they’ve provided that asks me to draw a misleading conclusion that falsely alarms that we need to start adapting.

July 29th, 2008 at 11:43 pm

Chip, I see that your 2004 study compared the trends in precipitation on the 10 wettest days with the overall trend for increasing precipitation. How is this different from the “heaviest 1% of rain events” as referred to in the report?

I take it you do not disagree with the figures on increases in regional downpours?

July 30th, 2008 at 4:54 am

Tom-

Thanks for your questions. Two answers:

1. On adaptation, we’ll have to disagree. Anytime you imply that adaptation is a necessary evil, you aren’t really giving it strong support.

2. The report is not discussing flooding when it says it is discussing flooding. It is discussing precipitation. They are not at all the same thing, and implying that precip = floods is in error, and misleading.

Thanks.

July 30th, 2008 at 5:09 am

Roger,

You mentioned something about a Congressional mandate; it would be helpful if you could post it. I spent about 15 minutes rummaging around their “about” section and couldn’t get a clear sense of their mission. They appear to somewhat function as a steering committee, comprised of reps from various Federal agencies.

Although they provide very useful budget data about Federal expenditures on climate change by various agencies, I was not able to find a budget for the committee itself.

Regarding the tone of the report, I found the following paragraph, also from the “About” section, very illuminating:

“Because of the scientific accomplishments achieved by USGCRP and other research programs during a productive “period of discovery and characterization” since 1990, we are now ready to move into a new “period of differentiation and strategy investigation”, which is the theme of the President’s Climate Change Research Initiative (CCRI).”

Less bloviatingly, this is the old “the science is settled – it’s time to start acting” attitude, which, factual errors notwithstanding, perhaps explains the advocacy-oriented tone of the report.

July 30th, 2008 at 12:07 pm

Tom,

We looked at the precipitation on each of the top 10 wettest days. The wettest day of the year starts to get pretty close to the wettest 1% in many parts of the country (perhaps it is only in the top 5% in the drier parts).

We did find that the wettest days were getting wetter–thus local downpours seem to be getting worse (if worse is defined by how much rain falls in a 24-hr period). On the other hand, we found that the proportion of annual rainfall contributed by the single wettest day was unchanged. In other words, the wettest day was not getting disproportionately wetter.

The results differed from the U.S. average in various regions.

-Chip

July 31st, 2008 at 12:17 am

Roger:

1. You say in your post that “the report has a strong bias against adaptation in favor of mitigation”; but the report clearly emphasizes adaptation over mitigation. As the report’s focus is on describing ongoing and expected impacts from climate change and on the areas where adapation is needed, adaptation gets much more attention than mitigation (which only gets limited initial mention).

Why do you say we’ll have to “agree to disagree”, without actually contesting what I’ve noted?

You now say that “Anytime you imply that adaptation is a necessary evil, you aren’t really giving it strong support”, but this is puzzling – what is adaptation, except finding ways to live with increased risks that cannot be avoided by trying to change the climate? And is the report implying that adaptation is a “necessary evil”, or that climate IS changing, so that adaptation is necessary?

Any any event, I am interested in hearing how you think the report ought to describe why adaptation is important.

2. On flooding, you intially said that “in the U.S. there has been no increase in streamflow and flood damage has decreased dramatically as a fraction of GDP. Thus the report reflects ignorance on this subject or is willfully misleading.” I asked you specifically whether the precipitation figures they used are wrong, or whether you just want more nuance about how an increasingly wealthy society can better handle greater flooding risks; you have not responded to this.

You now say that the report erroneously and misleadingly implies that precip = floods. This is a different criticism, but I would note that (i) river flooding is obviously linked to precipitation and (ii) the report spends significant time also dicussing flooding from ocean storm surges.

July 31st, 2008 at 12:25 am

Chip, it does sound like your research is at odds with this: “the amount of precipitation falling in the heaviest 1 percent of rain events increased by 20 percent in the past century, while total precipitation increased by 7 percent,” though it’s difficult to know that we aren’t comparng apples and oranges and whether or not you agree on some regions while disagreeing on a national average.

However, if average rainfall is increasing, even if “the proportion of annual rainfall contributed by the single wettest day was unchanged” (as you conclude), doesn’t this mean that the number of days with heavy rainfall is increasing?

July 31st, 2008 at 4:31 am

paddikj-

The legislative mandate is Public Law 101-606:

http://www.gcrio.org/gcact1990.html

More details can be found here:

Pielke Jr., R. A., 1995: Usable Information for Policy: An Appraisal of the U.S. Global Change Research Program. Policy Sciences, 38, 39-77.

http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/admin/publication_files/resource-109-1995.07.pdf

July 31st, 2008 at 5:01 am

Tom-

The issues that you raise on adaptation and its definition are quite important, see:

Pielke, Jr., R.A., 2005. Misdefining ‘‘climate change’’: consequences for science and action, Environmental Science & Policy, Vol. 8, pp. 548-561.

http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/admin/publication_files/resource-1841-2004.10.pdf

It is exactly this definition of adaptation as “failed mitigation” that I object to. Adaptation will be necessary regardless.

On precip, I assume that the CCSP numbers are correct. But so what? These numbers are not directly (or even indirectly) related to flooding, which the passage I am discussing is about. It does not matter that the report talks about storm surge elsewhere. Just as aluminum tubes may be used in nuclear reactors in France, this fact doesn’t say anything about what is going on in Iran. It is not nuance I am looking for in this case. Once again, discussing precip trends in a passage about flooding, and flood damage, is highly misleading. It obviously fooled you, as you appear to think that the two are related in some way.

For further details on the relationship, see:

Pielke, Jr., R. A. and M.W. Downton, 2000. Precipitation and Damaging Floods: Trends in the United States, 1932-97. Journal of Climate, 13(20), 3625-3637.

http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/admin/publication_files/resource-60-2000.11.pdf

Thanks again for your comments

July 31st, 2008 at 8:44 am

Tom,

You write “However, if average rainfall is increasing, even if ‘the proportion of annual rainfall contributed by the single wettest day was unchanged’ (as you conclude), doesn’t this mean that the number of days with heavy rainfall is increasing?”

Yes! That is the whole point and one of the reasons we wrote the paper. Based upon the nature of precipitation and its daily distribution, when you get more total rain for a year more of it falls in heavier events–so making a big deal about this is acting as if it is unexpected in some way. As human populations place an increasing demand on water availability, it certainly seems that, having more total precipitation is more preferable than having less total precipitation. And, it is the inherent characteristic of rainfall that when you get more total rain, more of it falls in heavier events.

Basically, you can’t have both–more precipitation and less heavier events. Unless, of course you totally change climate regimes, say by moving to Seattle from Dallas.

The CCSP report (and its authors) seem to want to complain about water limitations AND more heavy rain. Why? Because, beyond anything else, they only want to push the idea that ALL climate change is BAD climate change. I have never encountered a bigger bunch of pessimists is all my life. What little good they do begrudge, they quickly follow-up with, something like “but it will only be temporary.”

The more time I spend with the CCSP Draft Report, the more disgraceful it becomes.

I’ll post more on this at our World Climate Report site in the days ahead.

-Chip

July 31st, 2008 at 9:32 am

Roger,

As mentioned above the more into the CCSP Draft Report I get, the more appalled I become.

It is as if it is a mere rehashing of all the pet projects of some of the authors–without any recognition that these pet projects have come under harsh criticism by knowledgeable and credible researchers.

For instance, I am interested in your take on the “Society” section, specifically the damages from extreme weather and insurance losses, say p.50 and 51.

Nowhere in the entire report can I find a single reference of yours despite much talk of flood damages, insurance losses, extreme weather, etc.–all topics that you have published extensively on. Instead I find prominently featured the Science study by Mills, and other papers that I believe that you have taken exception to in the past.

Nowhere is there any indication that the “facts” presented in the CCSP report may be questioned (or in many cases deeply criticized).

It is as if they think that if they just keep on saying the same things that eventually they will become true because the critics will simply give up and go away!

The same is true in the human health sections. Nowhere is any of the work that we have done demonstrating that Americans are becoming better adapted and thus less sensitive to (increasing) heat waves discussed. Instead, the section is dominated by the findings of work that we have heavily criticized for using improper techniques (e.g. failing to take into account that we are becoming less sensitive when making future projections). And as an added slap in the face, the only citation of any of our work is in support of something that we hardly discussed in the cited paper—in fact, the citation is largely inappropriate.

My take thus far is that the CCSP is a perversion of science. The more I read, the less convinced I become that this opinion will change.

-Chip

July 31st, 2008 at 3:29 pm

Hi Tom,

You write, “…but this is puzzling – what is adaptation, except finding ways to live with increased risks that cannot be avoided by trying to change the climate?”

I’m confused. I think you meant, “…cannot be avoided by *not* changing the climate.”

Is that right?

If I’m right, I have a couple responses:

1) You (and the report authors) seem to be under the impression that climate won’t change if “we” (see comment #2) stop emitting greenhouse gases. But climate has changed and will continue to change for the forseeable future (i.e., the next many decades) regardless of what is done now. Even if the entire world

2) Even if “we” (being the U.S.) stopped emitting GHGs completely, and immediately, the U.S. and world climate will change for the rest of this century, simply because the U.S. emissions are only 1/4 of the world’s emissions of GHGs.

For both those reasons, the “increasing risk” of which you speak won’t be avoided, even if Klatu comes down and makes the U.S.–or even the entire world–stand still tomorrow. So, as Roger points out, it’s simply wrong to portray adaptation as what will be needed if “we” fail to mitigate. Especially if “we” means the U.S. We’re going to have to adapt, no matter what.

Mark

August 1st, 2008 at 3:14 am

Chip, if you agree that since we’re getting (on average) more total rain, and that more of it falls in heavier events, then I presume you also agree that increase in days with heavier rain poses risks that we should be preparing for. It seems your only disagreement here is on the factual question of there’s been a disproportionate shift of rain towards heavy events. I look forward to hearing your other criticisms, though.

“As human populations place an increasing demand on water availability, it certainly seems that, having more total precipitation is more preferable than having less total precipitation.” There are value judgments embedded in this that I won’t address, but even conceding your view, having more precipation and a greater number of heavy rain days still leaves us with something to adapt to, doesn’t it?

Roger, first, perhaps you wish to see the adaptation agenda stated differently; if so, I’m interested in hearing it. Perhaps you wish that the report focussed simply on climate risks and opportunities for society to reduce exposure to them, irrespective of the question of whether man is contributing to an elevation of them? I hesitate to put words in your mouth; I do hope you will copy your comments on the draft CCSP here. However, from my own perspective, the approach of the draft report seems both fair and common sense – our society doesn’t assign our government the job of master risk analyzer and behavior micro-manager – people and enterprises generally analyze, accept and respond to risks on their own. So it seems appropriate for the government to approach domestic adaptation from the perspective of: we understand that climate is changing, at least partly because of human influences (that it is too late/impractical to undo), and these are the ways we expect such changes to be manifested. I don’t view this approach as “negative”, as you seem to.

Second, no doubt you will clarify in your comments on the report precisely HOW “discussing precip trends in a passage about flooding, and flood damage, is highly misleading.” But for now, you simply haven’t said why. Rather, you’ve said that I’ve obviously been “fooled” to think that river flooding and precipitation are related in some way”. I hope to be educated in due course, but meanwhile note that you yourself have stated that “there is a strong relationship between precipitation and flood damage”.

Mark, perhaps this is a clearer statement of my views: “adaptation is the attempt to maximize welfare in the face of climate risks that cannot be avoided. For society as a whole, it is the attempt to maximize welfare in the face of climate risks that society chooses not, or is unable, to avoid by climate mitigation measures”.

1. I certainly harbor no illusions that climate will stop changing if somehow we all magically stopped emitting GHGs tomorrow, and I think the report makes very clear that the authors think that the climate cannot stop on a dime and that there are further climate changes in the works, simply from the delayed effects of existing forcings.

2. Agreed (of course). Yes, we’re going to have to adapt, no matter what. But it’s perfectly appropriate to point out, like you do, that the reason that we have to adapt is that we simply CANNOT mitigate alone, or in time even if everyone else is on board.

Regards,

Tom

PS: Forgive the combined responses. It’s easier than logging in and out and in multiple times.

August 1st, 2008 at 6:30 pm

Tom,

Can you please cite one instance in human history where a civilization did not have to adapt to climate change.

My point here is that natural climate change has always happened and will never stop. Adaptation will always be required. Notions that CO2 mitigation will reduce the need for adaptation are unfounded when the need for adaptation to existing natural climate fluctuations and severe weather events is woefully inadequate.

Mitigation is expensive compared to adaptation. Money spent on mitigation reduces the money that can be spent on mitigation. Adaptation products have financial benefits regardless of climate change, for they reduce the cost of severe weather events. If society adapted to severe weather and natural climate variability, it would likely solve most of the issues associated with the prospects of man-made climate change. If why try to mitigate man-made climate change through CO2 mitigation, we will still be required to increase our adaptive abilities nearly as much as if we did no mitigation at all.

If climate sensitivity to increasing CO2 is about a third of what the IPCC reports, which many new studies are suggesting, than mitigation is not only a complete waste of money, but will likely have seriously negative societal consequences, like corruption and increased governmental power over the masses (the negative consequences being true regardless of the climate sensitivity).

The emphasis on mitigation in the global warming debate is largely insane.

August 1st, 2008 at 6:32 pm

The second line of my third paragraph should read:

“Money spent on CO2 mitigation reduces the money that can be spent on adaptation.”

August 1st, 2008 at 11:45 pm

Jim, I agree with much of what you have to say, while disagreeing on several:

- “Money spent on mitigation reduces the money that can be spent on mitigation [I presume you mean adaptation].”

This is certainly overstated, as there are many synergies between the two, as Roger and others keep pointing out. Moreover, it is conceptually wrong. Pricing carbon would not alter incentives by individuals or firms to adapt to a changing climate – where the primary adaptive response occurs. And if any carbon tax were fully rebated, it would actually leave the poor and middle classes better able to afford adaptive measures. At the government level, if carbon taxes are not refunded, they could of course be used to fund adaptive changes to infrastructure and governance, whether at home or in poorer countries.

Also, if we mitigated by migrating power supply from fossil fuels to nuclear, we would be better adapted as the nuclear fuel cycle is much smaller and self-contained, and thus less vulnerable than other power supply. Imposing carbon taxes would enhance our adaptability by leading to greater diversity in our energy sources and service technologies, both for power and transportation.

- “Can you please cite one instance in human history where a civilization did not have to adapt to climate change.”

Human societies are tremendously adaptive, and the technologically advanced market economies (especially if unhindered by too much government regulation and rent-seeking) are even more so. Our abilities to adapt continue to grow, and I have no doubt that humanity will survive whatever we are helping Nature to throw at us.

- “The emphasis on mitigation in the global warming debate is largely insane.”

A great part of our adaptability is not passive or reactive, but the ability to anticipate and head off potential problems. THAT is why so many of the “largely insane” as you put it – from AEI to Exxon, insurers, scientists, world leaders, defense analysts, leading economists and the Pope – favor measures to shift our economies away from fossil fuels. I`ve summarized just a few of them in this post:

http://mises.org/Community/blogs/tokyotom/archive/2008/06/27/top-demagogues-jim-hansen-florida-power-exxon-aei-margo-thoring-major-economists-george-will-prefer-rebated-carbon-taxes.aspx

Please also see Marty Weitzman`s “On Modeling and Interpreting the Economics of Catastrophic Climate”, FINAL Version July 7, 2008, http://www.economics.harvard.edu/faculty/weitzman/files/REStatFINAL.pdf.

Here`s what Cato said today about Weitzman: “There is merit to the argument that society should consider a policy response to the threat of global warming. A small chance of an enormous calamity equals a risk that may deserve mitigation. That’s why people buy insurance, after all.” http://www.cato-at-liberty.org/2008/08/01/choosing-what-to-worry-about/

Regards,

Tom