Cutler and Glaeser on Why do Europeans Smoke More Than Americans? Part II

April 27th, 2006Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

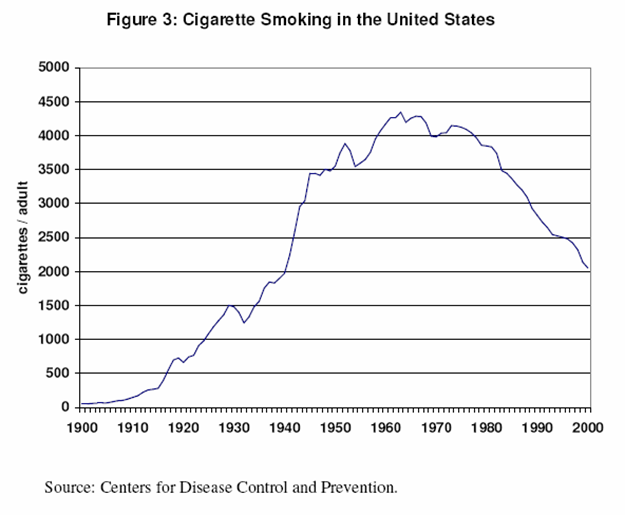

This is a second post discussing a paper by two Harvard economists, David Cutler and Edward Glaeser, available at the National Bureau of Economic Research that raises some interesting questions about the role of science and advocacy on the smoking issue. In this post I’d like to ask some questions about Figure 3 in that paper, reproduced below. For me, Figure 3 raises some really interesting questions about the relationship of science, advocacy, and societal outcomes for which I really have no answers for. I am hoping that Prometheus readers can point me to serious, scholarly literature that might explain what is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3 shows an increase in smoking in the U.S. through about 1950, broken up only by the Great Depression. There is then a drop off, which Cutler and Glaeser attribute to a first “health scare” about cigarettes which appeared first in the scientific literature and then in the popular media. The upward trend then resumes until the 1960s, a few ups and downs follow, and then, remarkably, from about 1970 on, a steady, almost monotonic decrease.

The question I have is, given these trends, how can one identify the effectiveness of advocacy for and against smoking, and in particular the role of science, uncertainty, and so-called “junk science” in outcomes as measured by societal outcome, in this case the number of cigarettes smoked per adult.

I have thought a good deal about this graph and it seems to show perhaps a number of things, which I suggest below.

1. In the battle over smoking efforts to deny a link between smoking and health risks seems to have been completely a lost effort. There is precious little evidence of the effects of such campaigns in this data. Of course, one could argue that the rate of decrease would be larger without such campaigns, however, if that were the case one would probably expect to see shorter term effects as such campaigns are more or less successful over time. This is a puzzle.

2. There are likely population effects that need to be disaggregated. This is smoking per adult, and as national population grows, this perhaps reflects less people deciding to take up smoking rather than a large increase in people quitting. But such data would be worth gathering.

3. Interestingly, there seems to be no acceleration of the trend in reduction of smoking as the scientific basis for a link between smoking and health risks became much stronger over time. The rate of change in this graph seems at a glance to be about the same in 1975 as it was in 1995. If there was a tight relationship between scientific understandings and societal outcomes, I’d hypothesize an ever increasing rate of change on this issue, especially as the pro-smoking media campaigns have waned. Now it could be that a bunch of complex factors conspire to randomly keep the rate of change in balance, and more analysis would be needed to determine this.

4. To me this data suggests a similarlity with data and findings in other areas of science. Specifically, science has a huge role in getting a subject onto the “agenda” of decision making, but after that, its role is very much dimished and subsumed to other factors, such as cultural, social, and political. If this is correct, it would require some deeper understanding about the role of advocacy relatd to scientific issues and the efficacy of using science as a tool of advocacy. This begs the question — why has anti-smoking advocacy been so successful over time? The throwaway answer that increasing scientific certainly is the key does not seem to jibe with this data.

For me this graph opens up some fundamenal questions tha arise at he intersection of science, advocacy, societal outcomes. I am motivated enough to follow this up with some actual research, so I’d welcome any comments and suggestions. The case of smoking/science is often raised in discussions of climate change and other areas as an analogy, but I am not convinced that such analogies are based on anything more that supposition, guesses, and assumptions.

April 27th, 2006 at 3:31 pm

Roger,

Sorry that I don’t have more to offer than just an observation and a theory, but here goes.

Even before WWII cigarettes were referred to as ‘coffin nails’. The common man was already well aware that cigarettes often led to or aggravated respiratory problems. The common man was aware that a life of smoking was often a shorter life. The common man did not care, because smoking was cool at first, and addictive in the long run.

The average Joe did not need scientific proof to know the effect of long term cigarette smoking. It was the lawyers who needed proof to win the law suits. The science just confirmed what the population already knew. It really did not change the perspective of the people.

The knowledge (in the general population) that cigarette smoking is unhealthy and will shorten life has changed little in the last 70 years. The graph is more a representation of societies feelings towards the practice of cigarette smoking, not a result of increased scientific knowledge.

(The dip in the early fifties might be a response to all the newborn babies and young children in homes around that time. New parents may have reduced their consumption of cigarettes in consideration of the little ones. Just a theory.)

In short, the science just confirmed what was already accepted knowledge. Therefore, it didn’t have any real impact on peoples behaviour in and of itself. The gradual shift in societies view of cigarettes from ‘cool’ to ‘dirty’ explains the graph much better.

In contrast, the average Joe has no personal knowledge of anthroprogenic climate change. In the past, there were good years and bad years; cold periods and warm periods. Decades were the rains fell and the crops were good. Decades were it didn’t fall as much and the fields turned to dust. From that perspective, there is nothing ‘climatologically’ different today.

It is only through ’science’ that the average person would even be aware that there might be problem with climate change. They certainly can not sense a problem from their own personal experience. Unlike cigarettes, the climate change ‘problem’ is only revealed through science, and, specifically, through climate models. Without the models predicting calamity, the average citizen would not be worried about it in the least.

Smoking deniers were simply trying to win lawsuits, by demanding proof. They already knew what the science would reveal, for the evidence was all around, but not ‘proven’.

AGW skeptics are not denying any physical evidence, just the ability of computer models to predict future climate. AGW skeptics keep pointing to the available evidence as an indication that the models are overblown!

There is really no comparison between AGW skeptics and the deniers of the health effects of cigarettes. They are completely opposite in methodology, motivation and purpose.

There is also no point in arguing that ’science’ does not influence populations by pointing to the lack of influence science had on cigarette smoking. It had no influence because it didn’t change what society already knew. In AGW, ’science’ is the only source of information for the masses on the subject. How that science is presented has a very large impact on society.

April 28th, 2006 at 7:23 pm

For the effects of denying the harm of tobacco see Figs. 2 and 3 at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4843a2.htm#fig1

which clearly show that there has been little progress in reducing smoking among women and starting smoking in young teens across the board except for African Americans.

BTW, the notations on Fig 1 (the same one that Roger showed above) pretty much puts the lie to Jim Clarke’s statement. The common man may have called ciggies coffin nails, but by G_d, when he had em’ he smoked em.

April 28th, 2006 at 7:54 pm

Eli- Thanks much for this link, good stuff. One response, you write, “For the effects of denying the harm of tobacco …”

How do you know cause (denial) and effect (trends in societal smoking outcomes)?

Thanks.

April 28th, 2006 at 8:21 pm

Hi Roger, you might start by reading the documents at http://tobaccodocuments.org/ Let us put it this way, there was an impressive FUD campaign and there are many studies which show that it had more than a marginal effect.

April 28th, 2006 at 8:33 pm

Eli- You write, “there are many studies which show that it had more than a marginal effect.”

Good. Some citations to these studies would be most useful. Thanks.

April 29th, 2006 at 9:32 pm

I have provided some rather long and detailed answers to questions about tobacco mortality http://rabett.blogspot.com/2006/04/tobacco-mortality.html and the effectiveness of the tobacco companies responses http://rabett.blogspot.com/2006/04/effective-tobacco-advertising.html.

April 29th, 2006 at 9:57 pm

You ought to just ask Stanton Glantz directly. I’m pretty sure what you’re looking it is a tiny slice of the process by which the tobacco industry transferred its marketing and sales effort away from the US to the Third World around 1970, staying ahead of the public health people by about ten years — it’s been well documented.

This is cherry-picking to try to argue that nothing happened as a result of the long battle to dig out the fake science. Anything under Google Scholar with Glantz as a coauthor will get you started understanding this rather deep and wide area of public health research. The British Medical Journal is a good place to search as well.

April 30th, 2006 at 6:25 am

Hank, Eli- Thanks for your comments. But you grossly misread my post if you think that I am trying “to argue that nothing happened as a result of the long battle to dig out the fake science.”

Let’s be clear — I am not trying to argue this point. I am trying to understand WHAT exactly has been the effect on societal outcomes of the long battle over smoking science. Cutler and Glaeser take a swing at part of this question, imperfectly in my view. So I am looking for more science on this subject. It seems from the literature I have seen that this question has not been rigorously answered.

From your replies it appears that you don’t have the answer either. But if you do come up with specific references to peer reviewed literature, please do share them.

Thanks!!

April 30th, 2006 at 9:54 am

Roger, I’m saying if you haven’t talked to Stanton Glantz, you should pick up the telephone and call him. This isn’t an obscure, unstudied area. Asking the Internet to do research is too naive.

April 30th, 2006 at 10:11 am

Hnak- Thanks much.

April 30th, 2006 at 10:21 am

Hank, sorry for the typo …

April 30th, 2006 at 12:10 pm

’s’OK. If I didn’t have the flu I’d try to find you the references at tobaccodocuments.org. I hope you get Dr. Glantz to participate here.