Skepticism’s Permanence – A Political Reality

October 16th, 2008Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

Rather than a stodgy old field with a few loose ends to tie up, climate science is increasingly looking like a Rube Goldberg device. Lucia Liljegren, of Argonne National Lab and expert brownie chef, continues her thoughtful, patient, and nuanced exploration of scientific issues related to comparing global surface temperatures in observations and models.

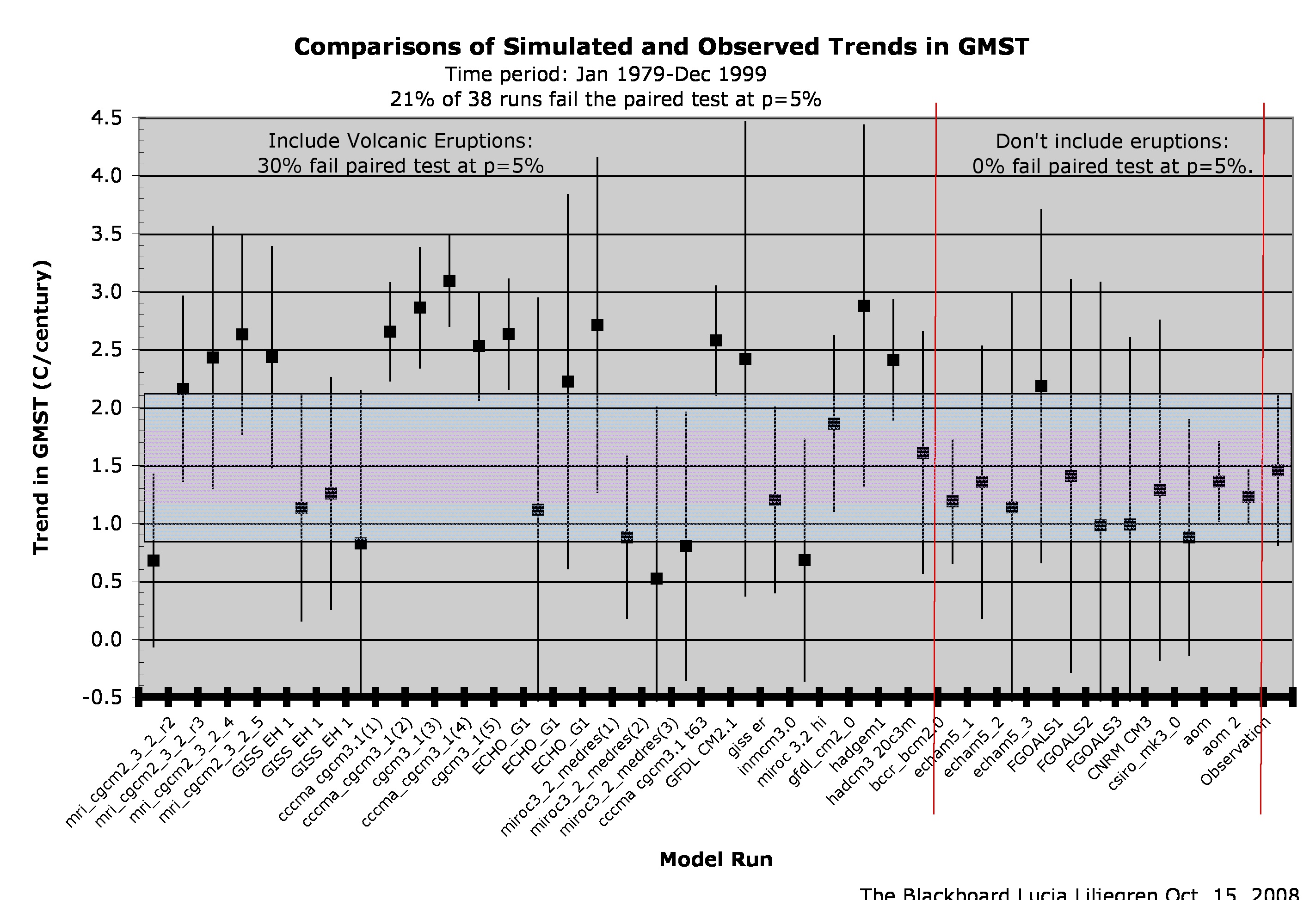

In the first post of a series (and what I hope will one day appear in the peer reviewed literature), Lucia applies a number of statistical tests from a recent paper by Santer et al. (written to refute the nefarious skeptical authors of Douglass et al., please find links at Lucia’s place) to the global mean surface temperature (GMST) record. What she finds is quite interesting (and indeed you should read her full post), specifically the tests that Santer et al. apply to tropospheric temperature trends, when applied to the global trends lead one to a conclusion that:

. . . the best estimate of the trend from 19 of the 38 individual [IPCC model] runs lie outside the +2σ confidence intervals for the observations of GMST. One might ordinarily expect roughly 5% of the data to fall outside the range: 19/38 is 50%. That so many individual runs are inconsistent with the observations may suggest…. (Dare I say it?), …..that the trends predicted by models may be inconsistent with the observation!

[UPDATE 10/17: Figure below updated.]

Now Lucia is quite properly very aware of uncertainties and caveats, so she concludes with:

. . . the observations do show statistically significant warming. The fact that the models predictions appear inconsistent with the observations does not erase that conclusion. The inconsistency between models and observations only affects the assessment of the likely accuracy and precision of models relative to other methods of forecasting trends in GMST.

I am sure that the consensus guys will explain all of this for us, and probably throw in some character assassination and accusations of shamefulness for extra credit. But the general point should not be missed — science does not work in a neat linear fashion moving from uncertainties to certainties. There is plenty of room for skepticism in discussions of science, including water cooler conversations and on blogs, and even the peer reviewed literature. We want people asking why, and looking for inconsistencies. In fact, such skepticism often drives new knowledge. Santer et al. would not exist except for the prior publication of Douglass et al., and responses to Lucia won’t exist except for her posing a difficult challenge.

For those who say, “well skeptical views get in the way of my political agenda” the proper answer is “tough luck.” If you can’t advance a political agenda in the face of the realities of scientific uncertainties that may grow or recede unpredictably, then you haven’t really developed a very robust political agenda. Trying to enforce certainty in science will thus do more to bring politics into science than anything else.

Climate policy should be robust to skepticism, because skepticism is not going away.

October 17th, 2008 at 7:00 am

Insightful as ever.

October 17th, 2008 at 7:28 am

“Climate policy should be robust to skepticism, because skepticism is not going away.”

Nor should it.

October 17th, 2008 at 8:41 am

“Rather than a stodgy old field with a few loose ends to tie up, climate science is increasingly looking like a Rube Goldberg device.”

That’s because the ’science is settled’ argument is and always has been a myth. Climate science is extremely complex and, in many ways, poorly understood, but it is not a complex description of a simple process (a Rube Goldberg device). The description is complex because climate is very complex.

The reality of climate science, complexity and skepticism has not changed in 20 years. What seems to be changing is number of people who are finally realizing what that reality is, much to the chagrin of the majority that propagated the myth.

October 26th, 2008 at 3:46 pm

There’s a certain irony about this. If policy is not robust, emissions follow BAU (assuming no other feedbacks – always a bad idea). Eventually skepticism goes away or dominates because we get to find out if the models were right.

If policy is robust, emissions follow some other trajectory, and it remains popular to question whether climate is stable because of successful policy, or because GHGs never mattered in the first place.