UPDATE 2:40PM 3-15-08: Within a few hours of this post, as we might have expected, rather than contributing to the substantive discussion, a climate scientist chooses instead to tell us how stupid we are for even discussing such subjects. We are told that “until the temperature obviously and unambiguously turns up again, this kind of stuff is going to continue.” Isn’t that what this post says? For the “stuff” read on below.

Regular readers will recall that not long ago I asked the climate community research community to suggest what climate observations might be observed on decadal time scales that might be inconsistent with predictions from models. While Real Climate has decided to take a pass on this question other scientists and interested observers have taken up the challenge, no doubt with interest added by the recent cooling in the primary datasets of global temperature.

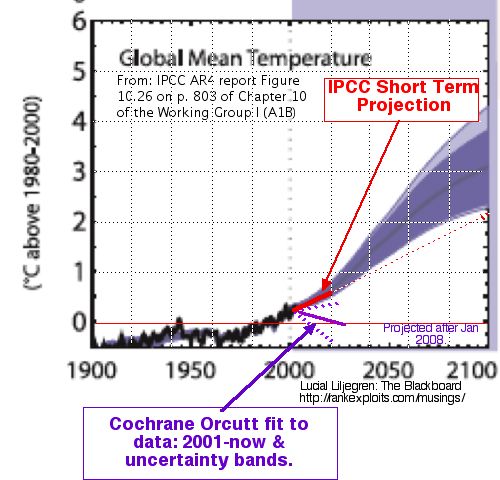

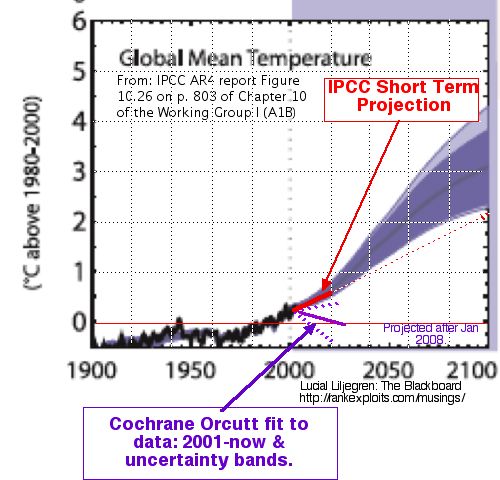

A very interesting perspective is provided by Lucia Liljegren, who has several interesting posts on observations versus predictions. The figure above is from her analysis. Her complete analysis can be found here. She has several follow up posts in which she discusses other aspects of the analysis and links to a few other, similar explorations of this issue. She writes:

No matter which major temperature measuring group we examine, or which reasonable criteria for limiting our choices we select, it appears that possible that something not anticipated by the IPCC WG1 happened soon after they published their predictions for this century. That something may be the shift in the Pacific Decadal Oscillation; it may be something else. Statistics cannot tell us.

It may turn out that this something is a relatively infrequent but climatologically important, feature that results in unusually cold weather . Events that happen at a rate of 1% do happen– at a rate of 1%. So, if recent flat trend is the 1% event, then 30 year trend in temperatures will resume.

For what it’s worth: I believe AGW is real, based on physical arguments and longer term trends, I suspect we will discover that GCM’s are currently unable to predict shifts in the PDO. The result is the uncertainty intervals on IPCC projections for the short term trend were much too small.

Of course, the reason for the poor short term predictions may turn out to be something else entirely. It remains to those who make these predictions to try to identify what, if anything, resulted in this mismatch between projections and short term data. Or to stand steadfast and wait for La Nina to break and the weather to begin to warm.

Those wanting to quibble with her analysis would no doubt observe that the uncertainty around IPCC predictions for the short term is undoubtedly larger that then IPCC itself presented. Lucia in fact suggests this in her analysis, making one wonder if uncertainties are indeed larger than presented, why didn’t the IPCC say so?

In 2006 my father and I wrote about the possible effects on the climate debate of short-term predictions that do not square with observations:

predictions represent a huge gamble with public and policymaker opinion. If more-or-less steady global warming does not occur as forecast by these models, not only will professional reputations be at risk, but the need to reduce threats to the wide spectrum of serious and legitimate environmental concerns (including the human release of greenhouse gases) will be questioned by some as having been oversold. For better or worse, a failure to accurately predict the changes in the global average surface temperature, global average tropospheric temperature, ocean average heat content change, or Arctic sea ice coverage would raise questions on the reliance of global climate models for accurate prediction on multi-decadal time scales.

In one of the comments in response to that post a climate scientist (and Real Climate blogger) took us to task for raising the issue suggesting that there was no really reason to speculate about such things given that, “I’ve pointed out that in the obs, there is no sign of > 2 yr decreasing trends.”

Another climate scientist commented that climate models were completely on target:

Re the possibility that the Earth is acting in a way that the models hadn’t predicted, I must say I’m pretty relaxed about that. Let’s wait a few more years and see, eh?

I have not yet seen rebuttals to Lucia’s analysis, or others like it (she points to a few), which are not peer-reviewed analyses, yet certainly of some merit and worth considering. There continues to be good reasons for climate scientists to begin more openly discussing the limitations of short-term climate predictions and the implications for understanding uncertainties. They have these discussions among themselves all of the time. For example, with a view quite similar to my own, Real Climate’s Gavin Schimdt suggests that if the full context of a prediction from a climate model is not understood, then:

model results have an aura of exactitude that can be misleading. Reporting those results without the appropriate caveats can then provoke a backlash from those who know better, lending the whole field an aura of unreliability.

None of this discussion means that the basic conclusion that greenhouse gases affect the climate system is wrong, or that action to mitigate emissions do not make sense. What it does mean is that we should be concerned about the overselling of climate predictions and the corresponding risks to public credibility and advocacy built upon these predictions.