Photography has always been an important tool for social scientists. Today, the pictures’s value as a data, communication tool and art is more relevant than ever: social media, digital photography and cell phones allow for almost anybody to document their environments. However, the limited use of photography essay in research and academia reminds us of the need to diversify our view about the field work and disaster studies.

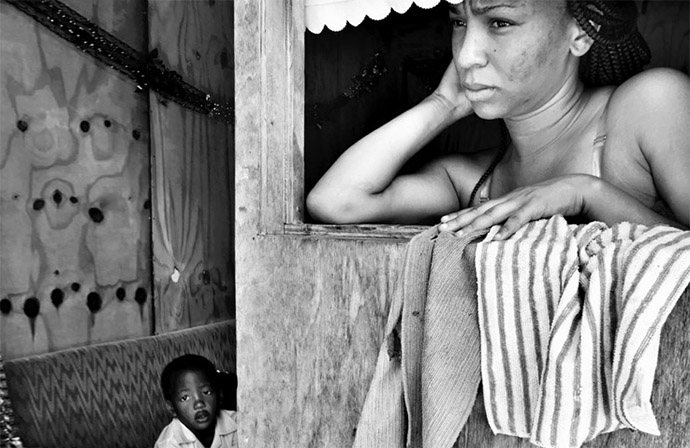

In the field and for this purpose, the act of taking pictures is not about mastering a technique, it is about the interaction with the people. It requires participant observation and consensus and freedom of the people to choose what they want to share. This interaction is the most valuable part of a photo photo essay because it gives “a voice” to the people, transforming the photographer into an intermediary to communicate a certain part of their reality. In other hand, pictures can speak by them self, leaving the viewer the option to connect and interpret connect and interpret the images.

The worst disaster in history of Dominica

In September 2017 Category 5 Hurricane Maria struck Dominica before pursue its trajectory to Puerto Rico. The small island (population 74,000) in the eastern Caribbean between Guadeloupe and Martinique was sweep out for the first time by a Category 5 hurricane since records began. The devastation in Dominica was massive, with around 90 percent of houses roofs damaged or destroyed. Also, crops and infrastructure were destroyed, leaving communities isolated due the landslides that blocked roads. For almost a year, around 50 percent of the habitants lived without electricity, according with testimonies of affected people. Eclipsed by the media coverage in Puerto Rico and often confused with the Dominican Republic, the Commonwealth of Dominica its recovering slowly. Almost two years after this extreme hydro-meteorological event, the impact remains noticeable by the number of destroyed houses along the island. Less visible is life in shelters, generally improvised schools without basic services as toilets and in some of them, running water and electricity. For those who do not have the resources to rebuild their homes, to live in shelters is the only choice: the impact in their health and capacity to recovery is jeopardized. For them, the hurricane Maria still is happening now. |

Approach

In February, 2019 in collaboration with the Office of Disaster Management of Dominica, we did a fieldwork to document with local agencies, stakeholders, local leaders, and the affected people, testimonies and interpretations of their actions to cope and survive during the emergency and the following months. Our idea was to identify some of the spontaneous actions that people developed in their communities after the hurricanes that could be taken as baseline for formal preparedness for disaster risk programs, based in the notion of Zero Order Responders, that reflect people’s creativity for deal with immediate needs through social cohesion and resourcefulness. However, in this case, the affected people are still facing the disaster consequences. When people remains in shelters they not fully recovery, they actually are becoming permanent affected: their chances to remain in poverty are high, feeding the social vulnerability circle. The people in the shelters don’t have a house to stay, for them the recovery “window” is getting closed; instead looking for coping mechanisms for recovery, they are dealing with an increase of their poverty conditions. |

|

Fernando Briones

Fernando Briones