Research Highlight |

|

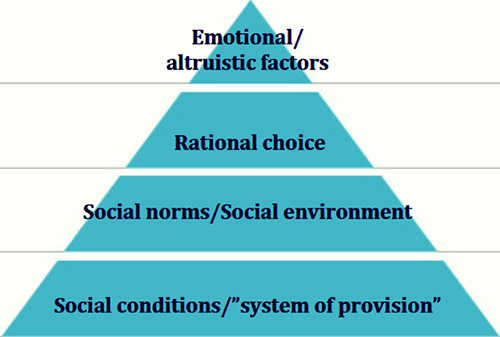

Individual Drivers for Environmental Engagementby Gesa LuedeckeResearch on environmental awareness, environmental psychology and social psychology paves the way to help understand individual decision-making processes towards environmental engagement. However, research on individual behavior is still a challenge as there are numerous variables that feed into those decision-making processes and play a central role along the process of definition and internalization of attitudes and opinions. When we look at how people’s brains work and what receives the most attention on an everyday life basis, we find an interesting pattern behind different theoretical and empirical approaches from socio and environmental psychology that describe motivations in a way that suggests to classify them hierarchically. In this hierarchy of motivations, we find emotions on top of the pyramid as the first and less strong level in terms of long-term impacts. Emotions can be a powerful system, but are often situational, short-termed, and influence our decision making on a day-to-day basis, while we learn through positive as well as through negative reinforcement. Many decisions we make refer to rational choices we take by making individual cost-benefit analyses in certain situations (assessing resource input in terms of money, time, and effort). In this context individuals evaluate the relation between input of resources and the anticipated output or added value of the planned behavior. This motivation often overshadows emotions in the long run.

Finally, there is the level of social infrastructure (at the bottom of the pyramid) that needs to be provided in terms to be able to conduct a planned behavior or maintain a certain activity. Infrastructural constraints to action can limit any sort of intended behavior, such as financial constraints, reduced sense of personal agency, and limited service provision (e.g. no accessibility or availability of infrastructure). Sometimes the four different motivation levels intertwine. These so called ‘motive alliances’ can build strong bonds and become more effective as long-term motivations than single level motives. Qualitative in-depth interviews with 25 individuals were conducted to reveal connections between motivational aspects and behavioral intentions and outcomes regarding climate adaptation and mitigation. The aim of this study was to unveil patterns from individual climate awareness, knowledge, and commitment to detect an existence of the four levels that have been carved out above. Results of the study show that information-based knowledge about climate change does not necessarily lead to a better understanding or commitment towards climate-related issues. Above, the interviewed individuals did not recognize a difference between climate mitigation and adaptation, which suggests there is no clear idea about what can actually be done on an individual level to tackle climate change or adapt to it. Therefore, it is also important to focus on solution-based knowledge (e.g. offer concrete tips for taking action) in climate-related issues. Emotions play a central role in climate change related issues, although they are mostly based on short-term effects and overlaid by rational motives that are mentioned as justification for not becoming engaged in climate-related issues. Findings suggest that social conditions (system of provision) finally constrain the behavioral intention as limiting factors as socio-structural motives often overlie altruistic (emotional), rational and normative motivations, which can only have a long-term effect in combination with stronger motives. Thus, the study overall finds support for the hierarchy of the four motivation levels beyond short-term effects. Gesa Lüdecke |

Gesa Luedecke, a Visiting Fellow at the Center, authored the Research Highlight for this issue of Ogmius. Gesa studied Environmental Sciences at the University of Lueneburg, Germany with a focus on environmental communications, sustainability and media as well as informal learning. She holds a Diploma degree in Environmental Sciences and a Ph.D. in Sustainability Sciences from Leuphana University. She has ongoing interests in environmental and sustainability communication, climate change and sustainability communication via media, media communication and sustainable behavior as well as in inter- and transdisciplinary studies. Her research focus is on the influence of media communication about climate change on individual behavior. With her experience in transdisciplinary research, Gesa is seeking to provide support for cross-disciplinary collaborations on the themes of media communication and social learning for decision-making in climate-related issues.

Gesa Luedecke, a Visiting Fellow at the Center, authored the Research Highlight for this issue of Ogmius. Gesa studied Environmental Sciences at the University of Lueneburg, Germany with a focus on environmental communications, sustainability and media as well as informal learning. She holds a Diploma degree in Environmental Sciences and a Ph.D. in Sustainability Sciences from Leuphana University. She has ongoing interests in environmental and sustainability communication, climate change and sustainability communication via media, media communication and sustainable behavior as well as in inter- and transdisciplinary studies. Her research focus is on the influence of media communication about climate change on individual behavior. With her experience in transdisciplinary research, Gesa is seeking to provide support for cross-disciplinary collaborations on the themes of media communication and social learning for decision-making in climate-related issues.

Social norms can also heavily influence our decision making in certain situations. As individuals we do not live in social vacuums, but are part of our social environments and their norms and values. We often think we act independently from others, but most of the time our decisions and activities are embedded in and adapted to external norms and behavior patterns.

Social norms can also heavily influence our decision making in certain situations. As individuals we do not live in social vacuums, but are part of our social environments and their norms and values. We often think we act independently from others, but most of the time our decisions and activities are embedded in and adapted to external norms and behavior patterns.