Research Highlight |

|

|

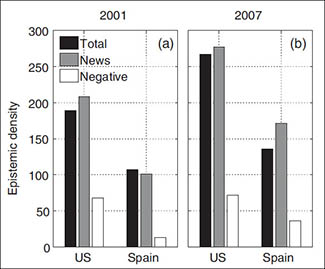

Is Climate Journalism Becoming More Cautious? Maybe SoA University of Colorado Boulder research team led by CIRES doctoral student Adriana Bailey, with CSTPR’s Max Boykoff and ENVS Ph.D. graduate Lorine Giangola – examined the “hedging” language - language that conveys uncertainty - used by journalists when reporting on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment reports. The team found that newspapers increased their use of hedging language over time, even though scientific consensus about climate change and its causes has strengthened. The team tracked “epistemic markers” in four major newspapers - the New York Times and Wall Street Journal from the U.S., and El País and El Mundo from Spain - in 2001 and 2007, the years in which the IPCC released its third and fourth assessment reports. Their analysis focused on articles about the IPCC and about the physical science of climate change, but did not evaluate news reports about the potential responses to climate change. Epistemic markers included any words or expressions that suggest room for doubt about the physical science of climate change, the scientific quality of the IPCC assessment reports, or the credibility of the panel. The research team counted words like speculative, believe, controversial, possible, projecting, almost, and largely, and modal verbs like could. They argued that the context in which these words appeared was also important. For example, the word uncertainty was marked as epistemic in the phrase “…substantial uncertainty still clouds projections of important impacts…,” but it was not counted in the phrase “…uncertainty was removed as to whether humans had anything to do with climate change…” Both phrases appeared at different times in the New York Times. The U.S. newspapers used more hedging words than the Spanish newspapers in both years. In the 2001 articles, they counted 189 epistemic markers per 10,000 words in the U.S. newspapers, and 107 in the Spanish newspapers. In 2007, the density of epistemic markers increased to 267 in the two U.S. newspapers and to 136 in the Spanish newspapers. While the difference between the two countries was not surprising, given the divergent approaches that the U.S. and Spain have taken toward developing national climate policies, the researchers nonetheless did not expect to find an increase in hedging language over time. Though the study did not investigate why journalists started using more hedging language in climate reporting, the team identified multiple potential influences, including increased politicization of climate change and its impacts on journalism and public discourse, and the reporting of more detailed scientific findings and uncertainties. The researchers also found that reporters construct additional uncertainty by highlighting changes and surprises - describing differences between IPCC assessments or between scientific predictions and observations - without providing sufficient explanatory context as to why they occur. By identifying journalistic trends that construct uncertainty in climate science reporting, the study highlights linguistic patterns that can subtly shape climate science communications and help guide future discourse on climate science in the media. An article from the project was published in the journal Environmental Communication in Spring 2014. A related book chapter will appear in the Spanish text Periodistas, medios de comunicación y cambio climático in Winter 2015. Lorine Giangola |