Monthly Summaries

Issue 71, November 2022

[DOI]

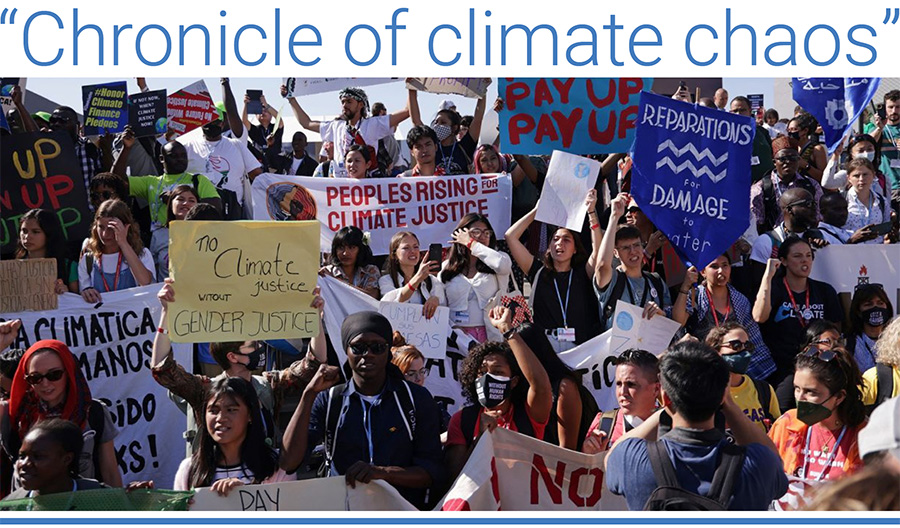

Climate activists staged a number of protests during the conference, demanding end of fossil fuels and climate finance. Photo: Sean Gallup/Getty Images.

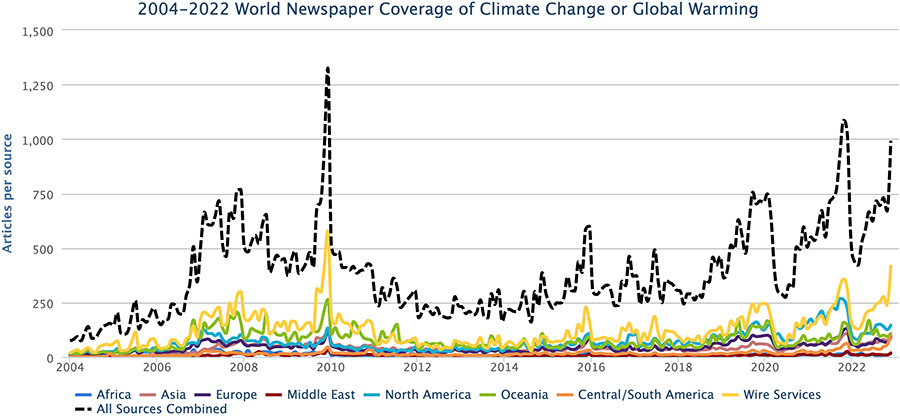

November media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe increased 41% from October 2022 but remained 12% lower than November 2021 levels. In a larger context, the levels of November 2022 coverage was the fourth highest monthly total, following December 2009, November 2021, and October 2021. International wire services were a strong contributor to this increase as coverage in these sources jumped 76%. Radio coverage also rose 27% from October 2022. Compared to the previous month, coverage went up in all regions: Oceania (+15%), North America (+17%), Asia (+31%), the European Union (EU) (+40%), Africa (+57%), Latin America (+80%), and the Middle East (+122%). Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through November 2022.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through November 2022.

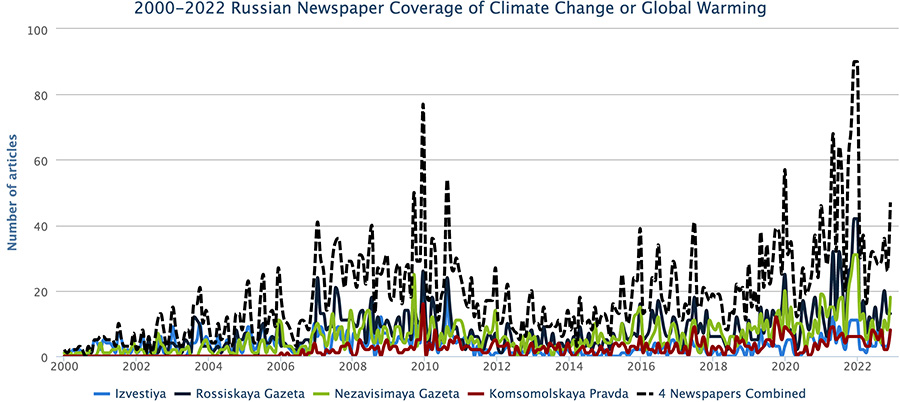

At the country level, United States (US) print coverage increased 20% while television coverage also was up 25% from the previous month. Among other countries that we at the Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) monitor, coverage increased in Canada (+11%), Finland (+15%), India (+15%), Denmark (+19%), Australia (+33%), Norway (+37%), the United Kingdom (UK) (+40%), Germany (+42%), Japan (+46%), Spain (+49%), Sweden (+75%), Korea (+77%), and Russia (+81%) (see Figure 2). Coverage in November 2022 only decreased at the country level in those we monitor in New Zealand (-15%).

Figure 2. Newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming in Russian newspapers Izvestiya, Rossiskaya Gazeta, Nezavisimaya Gazeta, Komsomolskaya, and Pravda from January 2000 through November 2022.

Turning to the content of coverage, in November media coverage featured many political and economic themed media stories about climate change or global warming. To illustrate, the United Nations (UN) climate negotiations (COP27) in November generated many media accounts. For example, in the lead up to the two-week event, Washington Post reporters Brady Dennis and Harry Stevens wrote, “Last fall, at a high-profile global climate summit in Scotland, the countries of the world embraced what seemed like a significant commitment in the quest to combat climate change. Acknowledging that progress had been too slow, leaders agreed to “revisit and strengthen” their national climate targets if possible over the coming year — rather than waiting every five years, as envisioned under the 2015 Paris climate accord. The push came as part of the effort to hold average global warming to no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, compared with preindustrial levels — a key threshold past which scientists have said disastrous impacts become far more likely. But…almost none of the globe’s biggest emitters have come forward with stronger commitments. Few nations overall have ramped up their ambition, despite another year of floods, fires and other climate-related catastrophes. According to the independent Climate Action Tracker, as of Thursday only 21 countries have submitted updated national climate commitments as leaders are set to gather at the summit, which starts Nov. 6 in Egypt — and not even all those newer plans contain more ambitious goals. Meanwhile, another 172 countries have not updated their targets, the group said.”

Media attention was paid to elements of the COP27 negotiations such as ‘loss and damage’. For example, Wall Street Journal correspondent Eric Niiler reported, “The last eight years have each been warmer than all years before that period on record, according to a report by the World Meteorological Organization that was released Sunday as the United Nations opened two weeks of climate talks. The WMO, which is a branch of the U.N., combined multiple scientific studies to compare temperatures since record-keeping began in the late 19th century. The group also reported that the rate of sea-level rise has doubled since satellite measurements began in 1993. European glaciers are expected to suffer a record melt in 2022. Greenland’s ice sheet experienced rainfall, rather than snow, for the first time in September”. Meanwhile, BBC journalist Esme Stallard noted, “Secretary-General Antonio Guterres was responding to a UN report released on Sunday saying the past eight years were on track to be the warmest on record. More than 120 world leaders are due to arrive at the summit known as COP27, in the Red Sea resort of Sharm el-Sheikh. This will kick off two weeks of negotiations between countries on climate action. COP27 president, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry, urged leaders to not let food and energy crises related to Russia's invasion of Ukraine get in the way of action on climate change…Mr Guterres sent a video message to the conference in which he called the State of the Global Climate Report 2022 a "chronicle of climate chaos".”

As the negotiations wrapped up with initial agreement on a loss and damage fund, many stories covered these developments. For example, CNN journalists Ivana Kottasová, Ella Nilsen and Rachel Ramirez reported, “The world has failed to reach an agreement to phase out fossil fuels after marathon UN climate talks were “stonewalled” by a number of oil-producing nations. Negotiators from nearly 200 countries at the COP27 UN climate summit in Egypt took the historic step of agreeing to set up a “loss and damage” fund meant to help vulnerable countries cope with climate disasters and agreed the globe needs to cut greenhouse gas emissions nearly in half by 2030”. Meanwhile, Wall Street Journal correspondents Matthew Dalton and Stacy Meichtry noted, “Poorer countries secured a deal at United Nations climate talks to create a fund for climate-related damage as part of a broader agreement that failed to yield faster cuts in emissions sought by wealthy nations to avert more severe global warming. The accord at the COP27 summit in this Egyptian seaside resort hands a victory to poorer nations that have demanded that money since the first U.N. climate treaty was signed three decades ago”.

As the second week of COP27 unfolded, leaders of the Group of 20 (G20) nations met in Bali, Indonesia and climate-related news emanated from that meeting as well. For example, New York Times journalists Brad Plumer, David Gelles, and Lisa Friedman reported, “At last year’s global climate talks in Glasgow, world leaders, scientists and chief executives rallied around a call to “keep 1.5 alive.” The mantra was in reference to an aspirational goal that every government endorsed in the 2015 Paris climate agreement: try to stop global average temperatures from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels. Beyond that threshold, scientists say, the risk of climate catastrophes increases significantly. Now, 1.5 is hanging on for dear life. At the United Nations climate summit that is underway in this Red Sea town, countries are clashing over whether they should continue to aim for the 1.5-degree target. The United States and the European Union both say that any final agreement at the summit, known as COP27, should underscore the importance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees. But a few nations, including China, have so far resisted efforts to reaffirm the 1.5-degree goal, according to negotiators from several industrialized countries. Failing to do so would be a major departure from last year’s climate pact and, to some, a tacit admission of defeat”.

Figure 3. Newspaper front pages stories in November with links to climate change and climate risks.

The month of November was also marked by media coverage about climate change or global warming with ecological and meteorological themes. Early in the month, hurricane Lisa’s landfall in Belize generated stories making connections with climate change. For example, Washington Post journalist Ian Livingston reported, “The tropical Atlantic remains unusually busy for November, with forecasters monitoring multiple systems at a time when activity is usually tamping down. After battering Belize as a hurricane Wednesday, where it caused flooding and wind damage, Tropical Depression Lisa is raining itself out over southeast Mexico. Meanwhile, Hurricane Martin, fueled by unusually warm ocean waters, is sweeping across the North Atlantic as the farthest-north hurricane on record during November. When Lisa and Martin coexisted as hurricanes on Wednesday, it marked only the third instance on record of multiple Atlantic hurricanes during the month. Statistically, a November hurricane should form in the Atlantic just once every two or three years…Human-caused climate change is warming ocean waters around the world, and research has already shown storms are gaining strength farther north than they used to.” An article in The New York Times by Christine Hauser and colleagues added, “The links between hurricanes and climate change have become clearer with each passing year. Data shows that hurricanes have become stronger worldwide during the past four decades. A warming planet can expect stronger hurricanes over time, and a higher incidence of the most powerful storms — though the overall number of storms could drop, because factors like stronger wind shear could keep weaker storms from forming. Hurricanes are also becoming wetter because of more water vapor in the warmer atmosphere. Also, rising sea levels are contributing to higher storm surge — the most destructive element of tropical cyclones.”

Scoping out, there were several news stories connecting meteorological events, disasters, and climate change. For example, Associated Press correspondent Drew Costley reported, “Ninety percent of the counties in the United States suffered a weather disaster between 2011 and 2021…Some endured as many as 12 federally-declared disasters over those 11 years. More than 300 million people — 93% of the country’s population — live in these counties… The National Centers for Environmental Information estimate over $1 trillion was spent on weather and climate events between 2011 and 2021. The report recommends the federal government shift to preventing disasters rather than waiting for events to happen”. Furthermore, La Vanguardia journalist Antonio Cerrillo noted, “The rise in temperatures observed in Europe in the last 30 years has been more than double the average increase in temperature recorded worldwide. On no other continent have temperatures been so high. And, as the warming trend continues, society, economies and ecosystems will be affected by exceptional heat episodes, forest fires and major avenues, among other effects. This is indicated by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in the report on the State of the climate in Europe prepared jointly with the Copernicus service and the European Union”.

In November, there continued to be a steady stream of scientific themes that emerged in media stories. To begin, a new report from World Weather Attribution that found connections between climate pollution and extreme rainfall attracted media attention. For example, Washington Post correspondent Amudalat Ajasa wrote, “Devastating floods this summer and fall displaced 1.5 million Nigerians and killed 612. In all of West Africa, more than 800 people died. Researchers have determined that human-caused climate change made the excessive rainfall behind the flooding 80 times more probable, according to a new analysis…The researchers, from the World Weather Attribution group, which evaluates the impact climate change has on extreme-weather events, made several related findings: The rainy season in West Africa was 20 percent wetter than it would have been without the influence of climate change. Throughout West Africa, prolonged rain events such as the one just experienced now have a 1 in 10 chance of happening each year; previously they were exceptionally rare. Short periods of intense downpours, which worsened the recent floods, have become twice as likely in the Lower Niger Basin region because of climate change. In their analysis, researchers uncovered what they described as a “very clear fingerprint of anthropogenic,” or human-caused, climate change. The analysis employed weather data and climate models to compare present climate conditions to the past. The researchers focused on the Lake Chad Basin, which saw a wetter-than-average rainy season, and the Lower Niger Basin, which saw short spikes in very heavy rain, to analyze climate change impacts. Running simulations with and without the influences of greenhouse gas emissions and aerosol pollution, the researchers were able to quantify how climate change altered the risk of extreme rainfall”.

Last, several cultural stories relating to climate change or global warming were evident in wider news coverage of climate change or global warming in the month of November. For example, global attention paid to the World Cup in Qatar also led to several stories making links to climate change. For example, Associated Press correspondent Suman Naishadham reported, “In the 12-year run-up to hosting the 2022 men’s World Cup soccer tournament, Qatar has been on a ferocious construction spree with few recent parallels. It built seven of its eight World Cup stadiums, a new metro system, highways, high-rises and Lusail, a futuristic city that ten years ago was mostly dust and sand. For years, Qatar promised something else to distinguish this World Cup from the rest: It would be ‘carbon-neutral,’ or have a negligible overall impact on the climate. And for almost as long, there have been skeptics — with outside experts saying Qatar and FIFA’s plan rests on convenient accounting and projects that won’t counteract the event’s carbon footprint as they advertise…in an official report estimating the event’s emissions, Qatari organizers and FIFA projected that the World Cup will produce some 3.6 million metric tons of carbon dioxide from activities related to the tournament between 2011 and 2023. That’s about 3% of Qatar’s total emissions in 2019 of roughly 115 million metric tons, according to World Bank data….Qatar famously moved the tournament to the winter to protect players and spectators from extreme heat. Even so, the gas-rich nation will air condition seven stadiums that are open to the sky. For water, it will mostly rely on energy-guzzling desalination plants that take ocean water and make it drinkable to satisfy the more than 1.2 million fans expected to touch down for the monthlong event. The Gulf Arab sheikdom is normally home to 2.9 million people. Qatar and FIFA say the largest source of emissions will be travel — mostly the miles flown from overseas. That will make up 52% of the total. Construction of the stadiums and training sites and their operations will account for 25%, the report said. Operating hotels and other accommodations for the five weeks, including the cruise ships Qatar hired as floating hotels, will contribute 20%. But in its report, Carbon Market Watch said those figures are not the whole story. It said Qatar vastly underestimated the emissions from building the seven stadiums by dividing the emissions from all that concrete and steel by the lifespan of the facilities in years, instead of just totaling them”. As a second example, El País journalists Miguel A. Medina and Clemente Álvarez wrote, “Idols of the ball, villains of the climate: the climate emergency does not reach the soccer bubble. Many of the World Cup stars in Qatar are part of the small percentage of the population that multiplies the emissions that warm the planet…any teams have oil companies and airlines as sponsors”.

Climate protests and demonstrations in November also led to media portrayals in various news outlets. For example, The Associated Press reported, “Hundreds of climate protesters blocked private jets from leaving Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport on Saturday in a demonstration on the eve of the COP27 U.N. climate meeting in Egypt. Greenpeace and Extinction Rebellion protesters sat around private jets to prevent them leaving and others rode bicycles around the planes”. As a second example, Guardian journalist Kevin Rawlinson wrote, “Parts of the M25 have been closed after activists demanding action on the climate crisis climbed gantries, police have said. The disruption followed seven arrests in Scotland Yard’s pre-emptive operation against the Just Stop Oil group”. A third example – covering protest actions at various European museums – by La Vanguardia journalists Teresa Sesé and Justo Barranco noted, “Two activists tried to glue Munch's The Scream to the National Museum in Oslo by proclaiming that “there will be no screaming when people die”, but museum guards prevented the action and called the police. A few days ago it was the Parisian Musée d'Orsay that stopped an activist who first tried to attack Van Gogh's self-portrait and then a Gauguin with tomato soup. A clear sign that Western museums are on high alert and taking urgent measures to confront the actions of climate activists, who in recent months have attached themselves to picture frames and thrown tomato soup against the windows of pieces iconic works such as Van Gogh's Sunflowers or Goya's Majas in the Prado”.

Thanks for your interest in our Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) work monitoring media coverage of these intersecting dimensions and themes associated with climate change and global warming.

- report prepared by Max Boykoff, Presley Church, Rogelio Fernández-Reyes, Jennifer Katzung, Ami Nacu-Schmidt and Olivia Pearman