Monthly Summaries

Issue 25, January 2019

[DOI]

Belgian protests against inaction on climate change drew more than 30,000 high school and university students to Brussels. Photo: AP/Francisco Seco.

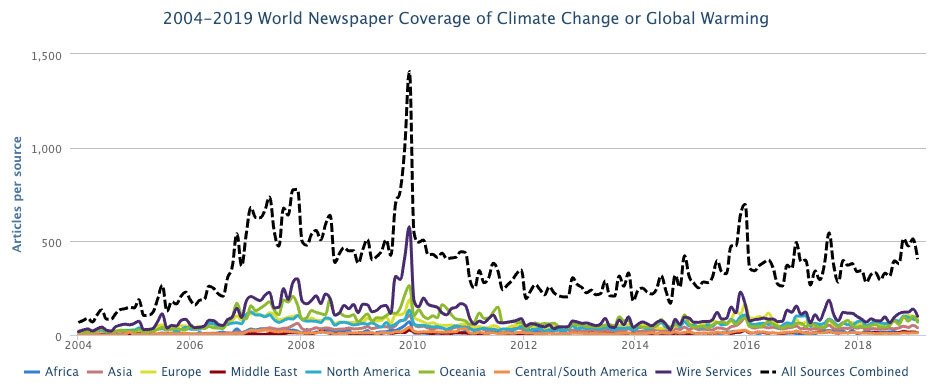

January media attention to climate change and global warming was down 20% throughout the world from the previous month of December 2018, but up just over 15% from January 2018.

While African coverage was up 21% from the previous month, it was down in all other regions, including North America where coverage was down 10% in January compared to the previous month of December 2018.

Figure 1 shows increases and decreases in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – over the past 181 months (from January 2004 through January 2019).

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in sixty-six sources across thirty-six countries in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through January 2019.

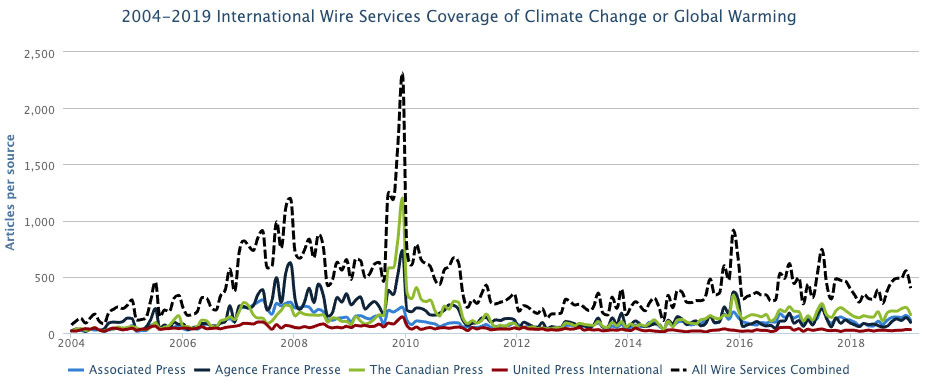

This month we introduce media monitoring of Public Broadcasting Services on United States television and additional monitoring across four wire services: The Associated Press, Agence France Press (AFP), The Canadian Press, and United Press International (UPI). We at the Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) now monitor sixty-six newspaper sources, six radio sources and seven television sources spanning thirty-nine countries with segments and articles in English, Spanish, German and Portuguese. In addition to English-language searches of ‘climate change’ or ‘global warming’, we now conduct searches of Spanish-language sources through the terms ‘cambio climático’ or ‘calentamiento global’, and commenced with searches of German-language sources through the terms ‘klimawandel’ or ‘globale erwärmung’ as well as Portuguese-language sources through the terms ‘mudanças climáticas’ or ‘aquecimento global’.

Figure 2. Media coverage of climate change or global warming across The Associated Press, Agence France Press (AFP), The Canadian Press, and United Press International (UPI) wire services.

Moving to considerations of content within these searches, Figure 3 shows word frequency data in Indian newspaper media coverage in January 2019.

In January, considerable attention was paid to political and economic content of coverage. Prominently, the movements of newly elected Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro captured media attention. From his inauguration in January, coverage focused on his efforts to commodify ecosystem services in the country. For example, Bolsonaro immediately sought to cede control of indigenous lands to agribusiness. Journalist Marina Lopes from The Washington Post reported that “Brazil’s new right-wing president opened the door Wednesday for more potential development and tree-clearing in the Amazon rain forest, giving the Agriculture Ministry oversight over which lands are granted protected status. The move by Jair Bolsonaro — in one of his first acts since his inauguration Tuesday — is seen as a victory for Brazil’s powerful rural lobby, which has long sought access to protected lands for logging, farming and other projects. It also signaled the apparent start of a new era of sweeping deregulation in Brazil, a country once lauded for its strides in environmental protection — including its stewardship of the world’s largest rain forest. Bolsonaro, a former army captain who was backed by the rural lobby, supports greater development of the Amazon, the assimilation of indigenous groups and reduction of environmental regulation”.

In January, considerable attention was paid to political and economic content of coverage. Prominently, the movements of newly elected Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro captured media attention. From his inauguration in January, coverage focused on his efforts to commodify ecosystem services in the country. For example, Bolsonaro immediately sought to cede control of indigenous lands to agribusiness. Journalist Marina Lopes from The Washington Post reported that “Brazil’s new right-wing president opened the door Wednesday for more potential development and tree-clearing in the Amazon rain forest, giving the Agriculture Ministry oversight over which lands are granted protected status. The move by Jair Bolsonaro — in one of his first acts since his inauguration Tuesday — is seen as a victory for Brazil’s powerful rural lobby, which has long sought access to protected lands for logging, farming and other projects. It also signaled the apparent start of a new era of sweeping deregulation in Brazil, a country once lauded for its strides in environmental protection — including its stewardship of the world’s largest rain forest. Bolsonaro, a former army captain who was backed by the rural lobby, supports greater development of the Amazon, the assimilation of indigenous groups and reduction of environmental regulation”.

Figure 3. Word cloud showing frequency of words (4 letters or more) invoked in media coverage of climate change or global warming in Indian newspaper sources. Data are from The Indian Express, The Hindu, Hindustan Times, and The Times of India.

In Europe, some coverage focused on a continuing trend toward decarbonization and electric transportation. For example, media focused on Germany’s announced plans in January to phase out all of its coal-fired power plants over the next two decades. In addition to abundant media attention in the German press, journalist Erik Kirschbaum from the Los Angeles Times reported, “the announcement marked a significant shift for Europe’s largest country — a nation that had long been a leader on cutting CO2 emissions before turning into a laggard in recent years and badly missing its reduction targets. Coal plants account for 40% of Germany’s electricity, itself a reduction from recent years when coal dominated power production”. As another example, coverage noted record-setting electric vehicle sales in 2018. Journalists Camilla Knudson and Alister Doyle commented, “Almost a third of new cars sold in Norway last year were pure electric, a new world record as the country strives to end sales of fossil-fueled vehicles by 2025... The independent Norwegian Road Federation (NRF) said on Wednesday that electric cars rose to 31.2 percent of all sales last year, from 20.8 percent in 2017 and just 5.5 percent in 2013, while sales of petrol and diesel cars plunged”.

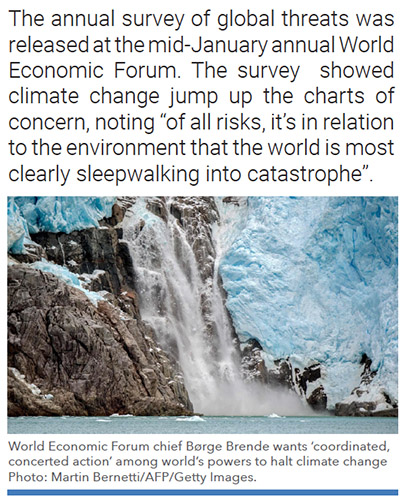

Meanwhile, the annual survey of global threats was released at the mid-January annual World Economic Forum. The survey showed climate change jump up the charts of concern, noting "of all risks, it's in relation to the environment that the world is most clearly sleepwalking into catastrophe". Journalist Joanna Sugdan from The Wall Street Journal reported, “The threat of a full-blown global trade war and rising political tensions between world powers are the dominant global risks, according to a report by the World Economic Forum ahead of its annual gathering in Davos, Switzerland, next week. Cyberattacks and climate change also feature high on the list of potential hazards drawn up from a survey of around 1,000 lawmakers, academics and business leaders for the group that organizes the Davos meeting”. Meanwhile, Guardian economics editor Larry Elliot wrote, “Growing tension between the world’s major powers is the most urgent global risk and makes it harder to mobilise collective action to tackle climate change, according to a report prepared for next week’s World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. The WEF’s annual global risks report found that a year of extreme weather-related events meant environmental issues topped the list of concerns in a survey of around 1,000 experts and decision-makers”.

Also in January, media covered ecological and meteorological dimensions of climate issues. For example, increases in jellyfish stings in Australia were attributed to changes in the climate. Washington Post journalist Rick Noack reported, “Authorities in Queensland, Australia, were forced to close beaches across the region over the weekend amid what local officials said was a jellyfish “epidemic.” Thousands of stings were recorded in Queensland last week, according to rescue organizations. While the vast majority of those stings were not life-threatening and were caused by “bluebottle colonies,” researchers say the number of more serious injuries from less common jellyfish is also at above-average levels. Some researchers also say this jellyfish infestation could be one more thing to blame on climate change”.

Also in January, media covered ecological and meteorological dimensions of climate issues. For example, increases in jellyfish stings in Australia were attributed to changes in the climate. Washington Post journalist Rick Noack reported, “Authorities in Queensland, Australia, were forced to close beaches across the region over the weekend amid what local officials said was a jellyfish “epidemic.” Thousands of stings were recorded in Queensland last week, according to rescue organizations. While the vast majority of those stings were not life-threatening and were caused by “bluebottle colonies,” researchers say the number of more serious injuries from less common jellyfish is also at above-average levels. Some researchers also say this jellyfish infestation could be one more thing to blame on climate change”.

However, most dominant in January media coverage of climate change was a polar vortex that gripped much of the upper Midwest of the United States. Part of the media story also became US President Trump’s response. For example, The Associated Press reporter Seth Borenstein wrote, “In the midst of a Midwest cold spell, President Donald Trump is pleading for global warming to come back, but it never went away. Just like the Arctic air invading parts of the U.S. because of wandering pieces of the polar vortex, Earth’s warmth appears a bit temporarily displaced. But scientific reports issued by the Trump administration and outside climate scientists contradict Trump’s suggestion that global warming can’t exist if it’s cold outside”. Meanwhile, CNN journalists Don Lemon and Chris Cuomo joked about the President’s confusion between weather and climate change.

Regarding media accounts focused on primarily scientific dimensions of climate change and global warming, the US government shutdown’s impact on ongoing scientific research on climate change garnered media attention. In a representative Washington Post article entitled ‘As shutdown continues, so does damage to U.S. science’, journalists Ben Guarino, Carolyn Y. Johnson, Sarah Kaplan and Lenny Bernstein reported, “Of the 800,000 federal employees furloughed or working without pay, thousands are researchers. These include agency scientists at the Agriculture Department, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Geological Survey. (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health, which were separately funded through September, are almost entirely safe from this shutdown.) Furloughed government scientists are banned from any form of work activity — they cannot so much as open an email. “The current government shutdown has far-reaching effects that put America’s scientific progress at risk. While there are reports that agencies such as NOAA and the USGS are still issuing alerts about weather and natural hazards, much of the scientific research into how to prevent these kinds of disasters has stalled,” said Christine McEntee, executive director of the American Geophysical Union. “This shutdown could affect the EPA’s ability to meet deadlines for assessing chemicals, and NOAA isn’t able to track fish for commercial harvesting or endangered species to protect them from passing ships.” She added, “Until funding is secured, many scientists employed by the U.S. government aren’t able to make important observations or analyze data to protect life, property and ecosystems here at home and abroad."

In other news, key scientific findings from new studies relating to climate change garnered attention. For example, that the world’s oceans have been warming more quickly than predicted generated considerable media coverage. The study in Science magazine by Lijing Cheng, John Abraham, Zeke Hausfather, and Kevin Trenberth entitled ‘How Fast are the Oceans Warming?’. USA Today journalist Doyle Rice noted, “Global warming isn't only cooking our atmosphere, it’s also heating up the oceans. The world's seas were the warmest on record in 2018, scientists announced Thursday. Also, ocean temperatures are rising faster than previously thought, a new paper said. Specifically, they're warming as much as 40 percent faster than an estimate from a United Nations panel just five years ago”. Meanwhile, CNN reporter Jen Christensen wrote, “For the new study, scientists used data collected by a high-tech ocean observing system called Argo, an international network of more than 3,000 robotic floats that continuously measure the temperature and salinity of the water. Researchers used this data in combination with other historic temperature information and studies. The study authors say the warming is happening because of climate change created by such human activities as the burning of fossil fuels”.

Furthermore, scientific findings from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that Antarctica is losing ice more than six times faster today than it did in the 1970s also garnered media attention. To illustrate, Associated Press journalist Seth Borenstein reported, “Scientists used aerial photographs, satellite measurements and computer models to track how fast the southern-most continent has been melting since 1979 in 176 individual basins. They found the ice loss to be accelerating dramatically — a key indicator of human-caused climate change. Since 2009, Antarctica has lost almost 278 billion tons (252 billion metric tons) of ice per year, the new study found. In the 1980s, it was losing 44 billion tons (40 billion metric tons) a year. The recent melting rate is 15 percent higher than what a study found last year”. Washington Post journalists Chris Mooney and Brady Dennis wrote, “Antarctic glaciers have been melting at an accelerating pace over the past four decades thanks to an influx of warm ocean water — a startling new finding that researchers say could mean sea levels are poised to rise more quickly than predicted in coming decades”.

Furthermore, scientific findings from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that Antarctica is losing ice more than six times faster today than it did in the 1970s also garnered media attention. To illustrate, Associated Press journalist Seth Borenstein reported, “Scientists used aerial photographs, satellite measurements and computer models to track how fast the southern-most continent has been melting since 1979 in 176 individual basins. They found the ice loss to be accelerating dramatically — a key indicator of human-caused climate change. Since 2009, Antarctica has lost almost 278 billion tons (252 billion metric tons) of ice per year, the new study found. In the 1980s, it was losing 44 billion tons (40 billion metric tons) a year. The recent melting rate is 15 percent higher than what a study found last year”. Washington Post journalists Chris Mooney and Brady Dennis wrote, “Antarctic glaciers have been melting at an accelerating pace over the past four decades thanks to an influx of warm ocean water — a startling new finding that researchers say could mean sea levels are poised to rise more quickly than predicted in coming decades”.

Across the globe in December, there was a range of stories that intersected with the cultural arena. For example, the news that renewable energy became Germany’s main energy source in 2018 (overtaking coal) attracted attention. For example, journalist Vera Eckert from Reuters reported, “Renewables overtook coal as Germany’s main source of energy for the first time last year, accounting for just over 40 percent of electricity production... The shift marks progress as Europe’s biggest economy aims for renewables to provide 65 percent of its energy by 2030 in a costly transition as it abandons nuclear power by 2022 and is devising plans for an orderly long-term exit from coal. The research from the Fraunhofer organization of applied science showed that output of solar, wind, biomass and hydroelectric generation units rose 4.3 percent last year to produce 219 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity. That was out of a total national power production of 542 TWh derived from both green and fossil fuels, of which coal burning accounted for 38 percent. Green energy’s share of Germany’s power production has risen from 38.2 percent in 2017 and just 19.1 percent in 2010”.

In addition, young people’s demonstrations for more coherent and substantial climate action across Europe attracted increasing media attention as the month of January unfolded. One day each week in January, students in Germany, Switzerland and Belgium walked out of school to protest European Union and nation-state government inaction on climate change. Early in the month, The Associated Press reported, “More than 10,000 students skipped school again in Belgium to join a march demanding better protections of the globe’s fragile climate. Despite the rain and cold, the colorful protest march in Brussels was bigger than the initial one last week. Banners reading “School strike 4 Climate” and “Skipping school? No. We fight for our future,” highlighted the march, which was free of incidents”. BBC also captured comments from some of the more than 12,000 students who took part in the protests in Brussels. Later in the month – as estimated sizes of the student groups has continued to grow – Washington Post journalist Rick Noack reported, “Now in their third week, the Belgian protests against inaction on climate change drew more than 30,000 high school and university students to Brussels, roughly triple the number of protesters last week”.

It seems that 2019 will be animated with political, economic, ecological, meteorological, cultural and scientific dimensions of climate change. We at MeCCO will be monitoring and analyzing these stories as they unfold. Stay strong and stay tuned in.