Monthly Summaries

Issue 42, June 2020

[DOI]

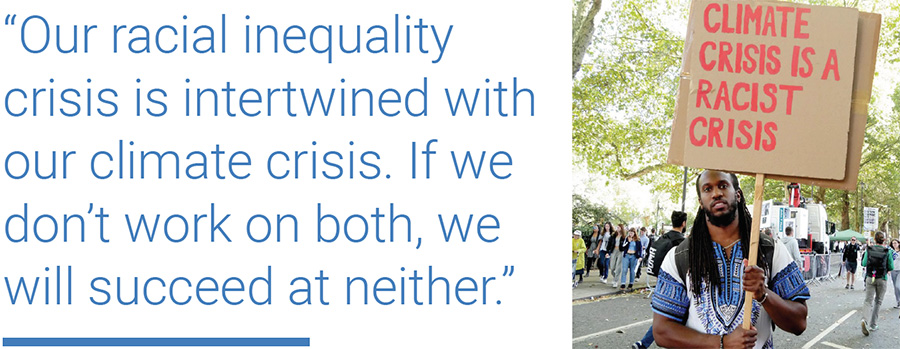

Ntale Eastmond, took to the protest in Central London in September 2019. Photo: https://eachother.org.uk.

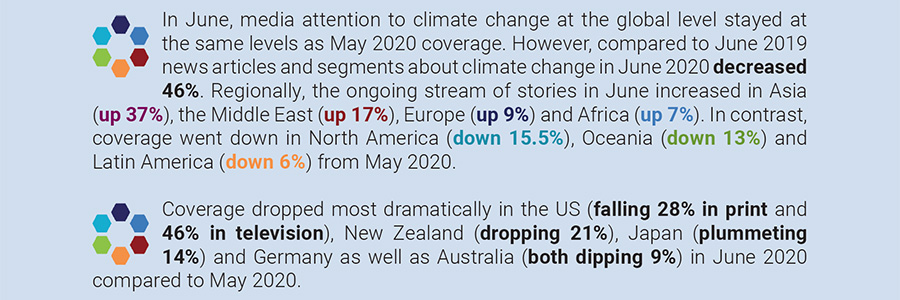

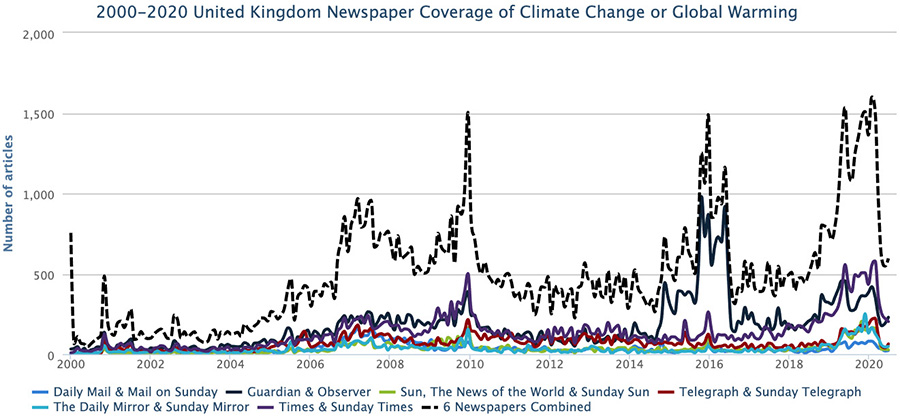

June 2020 brings us to a crossroads. Media coverage of climate change or global warming has dropped dramatically from the start of the year, and remains low. In June, media attention to climate change and global warming at the global level stayed at the same levels as May 2020 coverage. However, compared to June 2019 news articles and segments about climate change and global warming in June 2020 decreased 46%. Regionally, the ongoing stream of stories in in June increased in Asia (up 37%), the Middle East (up 17%), Europe (up 9%) and Africa (up 7%). In contrast, coverage went down in North America (down 15.5%), Oceania (down 13%) and Latin America (down 6%) from May 2020.

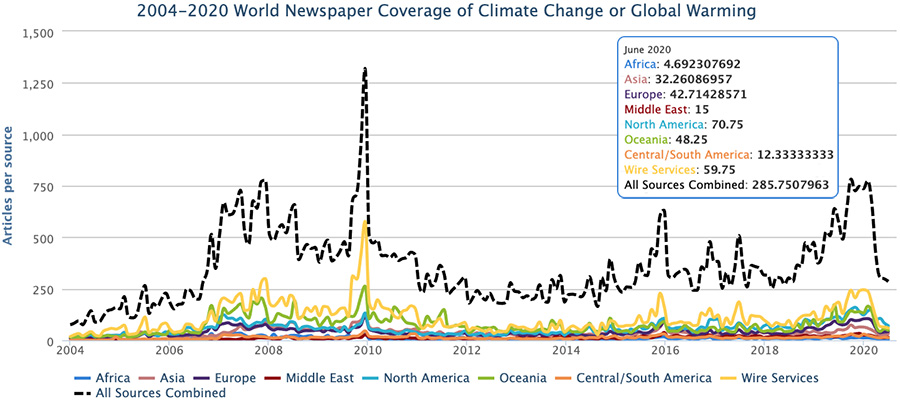

Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through June 2020.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through June 2020.

Figure 2. UK newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in The Daily Mail & Mail on Sunday, Guardian & Observer, Sun, The News of the World & Sunday Sun, The Telegraph & Sunday Telegraph, The Daily Mirror & Sunday Mirror, and Times & Sunday Times from January 2004 through June 2020.

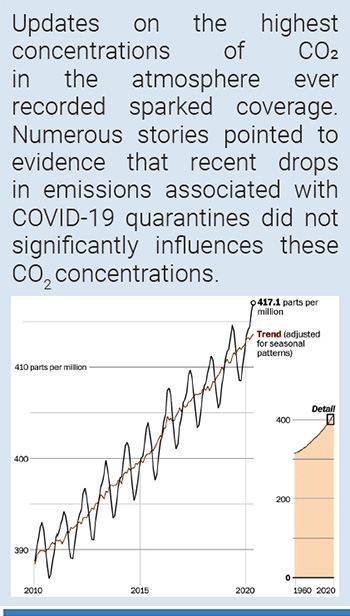

Mauna Loa Observatory measured a record monthly average atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration in May, typically the peak of the year. Source: NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory. |

At the country level, media coverage of climate change or global warming climbed most significantly in June 2020 from the month before in Russia (up 59%), Norway (up 40%), India (up 34%), the United Kingdom (UK) (up 9%), Spain (up 7%), Canada (up 4%) and Sweden (up 2%). Meanwhile, coverage dropped most dramatically in the United States (US) (falling 28% in print and 46% in television), New Zealand (dropping 21%), Japan (plummeting 14%) and Germany as well as Australia (both dipping 9%) in June 2020 compared to May 2020.

In June, scientific research and findings about various dimensions of climate change or global warming garnered media attention. For example, updates on the highest concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere ever recorded sparked coverage. Numerous stories pointed to evidence that recent drops in emissions associated with COVID-19 quarantines did not significantly influences these CO2 concentrations. For example, Washington Post journalists Andrew Freedman and Chris Mooney reported, “The coronavirus pandemic’s economic downturn may have set off a sudden plunge in global greenhouse gas emissions, but another crucial metric for determining the severity of global warming — the amount of greenhouse gases actually in the air — just hit a record high. According to readings from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the amount of CO2 in the air in May 2020 hit an average of slightly greater than 417 parts per million (ppm). This is the highest monthly average value ever recorded, and is up from 414.7 ppm in May of last year. Carbon dioxide levels are the highest they’ve been in human history, and probably are the highest in 3 million years. The last time there was this much CO2 in the atmosphere, global average surface temperatures were significantly warmer than they are today, and sea levels were 50 to 80 feet higher. The continuing rise in CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere may sound surprising in light of recent findings that the pandemic, and the associated lockdowns, had led to a steep drop in global greenhouse gas emissions, peaking at a 17 percent decline in early April. But the total amount of CO2 that winds up in the atmosphere is driven not only by human emission levels, but also through processes on the land surface (especially forests) and in the oceans that fluctuate on a yearly basis. According to a Scripps news release announcing the findings, CO2 emissions reductions on the order of 20 to 30 percent would need to be sustained for six to 12 months in order for the increase in atmospheric CO2 to slow in a detectable way.”

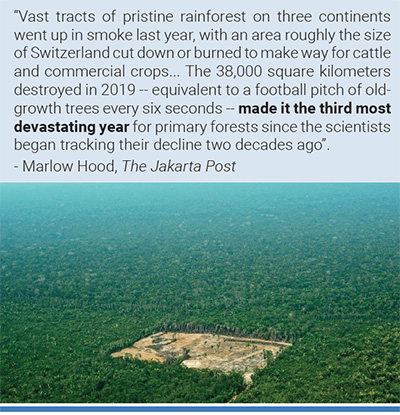

Deforestation in the Western Amazon region of Brazil. Vast tracts of rainforest on three continents went up in smoke, with an area roughly the size of Switzerland cut down or burned to make way for cattle and commercial crops. Photo: Carl de Souza/AFP. |

Moreover, new research connecting deforestation and climate change also generated media attention. In particular, findings from World Research Institute’s Global Forest Watch program permeated public conversations. For example, in an article entitled ‘Climate Change: Older Trees Loss Continue around the World’ BBC journalist Matt McGrath wrote, “Older, carbon-rich tropical forests continue to be lost at a frightening rate, according to satellite data. In 2019, an area of primary forest the size of a football pitch was lost every six seconds, the University of Maryland study of trees more than 5 metres says. Brazil accounted for a third of it, its worst loss in 13 years apart from huge spikes in 2016 and 2017 from fires. However, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo both managed to reduce tree loss. Meanwhile, Australia saw a sixfold rise in total tree loss, following dramatic wildfires late in 2019”. As another example of coverage, Agence-France Presse reporter Marlow Hood – writing in The Jakarta Post – noted, “Vast tracts of pristine rainforest on three continents went up in smoke last year, with an area roughly the size of Switzerland cut down or burned to make way for cattle and commercial crops... The 38,000 square kilometers destroyed in 2019 -- equivalent to a football pitch of old-growth trees every six seconds -- made it the third most devastating year for primary forests since the scientists began tracking their decline two decades ago. Tropical ecosystems are vulnerable to both climate change and extractive exploitation”.

The sun sets behind the Statue of Liberty as it is partially obscured by heat waves from the exhaust of a passing ferry on May 31, 2020 in New York City. Photo: Gary Hershorn/Getty Images. |

In June, media coverage of climate stories also drew on ecological and meteorological themes. For instance, NBC News reporter Emma Newberger noted that “The Earth had its hottest May ever last month, continuing an unrelenting climate change trend as 2020 is set to be among the hottest 10 years ever, scientists with the Copernicus Climate Change Service announced... It’s virtually certain that this year will be among the top hottest years in recorded history with a higher than 98% likelihood it will rank in the top five, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration”.

As another example, high temperatures in Siberia following a warm winter in that part of the Northern Hemisphere grabbed media headlines and stories. For example, Guardian journalist Damian Carrington wrote, “A prolonged heatwave in Siberia is “undoubtedly alarming”, climate scientists have said. The freak temperatures have been linked to wildfires, a huge oil spill and a plague of tree-eating moths. On a global scale, the Siberian heat is helping push the world towards its hottest year on record in 2020, despite a temporary dip in carbon emissions owing to the coronavirus pandemic. Temperatures in the polar regions are rising fastest because ocean currents carry heat towards the poles and reflective ice and snow is melting away. Russian towns in the Arctic circle have recorded extraordinary temperatures, with Nizhnyaya Pesha hitting 30C on 9 June and Khatanga, which usually has daytime temperatures of around 0C at this time of year, hitting 25C on 22 May. The previous record was 12C. In May, surface temperatures in parts of Siberia were up to 10C above average”.

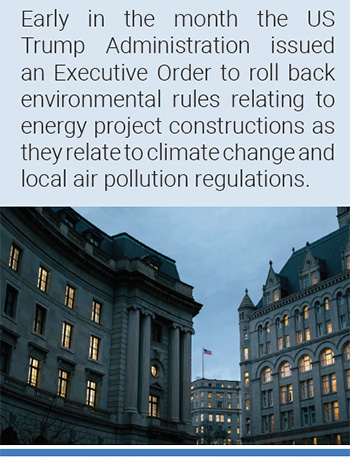

The offices of the Environmental Protection Agency, left, and the Trump International Hotel, right, in Washington. Photo: Alyssa Schukar/The New York Times. |

In June, our MeCCO monitoring also detected political and economic media coverage of climate change or global warming. In particular, early in the month the US Trump Administration issued an Executive Order to roll back environmental rules relating to energy project constructions as they relate to climate change and local air pollution regulations. For example, New York Times journalists Coral Davenport and Lisa Friedman reported, “President Trump signed an executive order that calls on agencies to waive required environmental reviews of infrastructure projects to be built during the pandemic-driven economic crisis. At the same time, the Environmental Protection Agency has proposed a new rule that changes the way the agency uses cost-benefit analyses to enact Clean Air Act regulations, effectively limiting the strength of future air pollution controls. Together, the actions signal that Mr. Trump intends to speed up his efforts to dismantle environmental regulations as the nation battles the coronavirus and a wave of unrest protesting the deaths of black Americans in Georgia, Minnesota and Kentucky. They will also help define the stakes in the 2020 presidential election, since neither effort would likely survive a Democratic victory. By changing the way the government weighs the value of the public health benefits, Andrew Wheeler, the E.P.A. administrator, would allow the agency to justify weakening clean air and climate change regulations with economic arguments. Mr. Trump’s executive order would use “emergency authorities” to waive parts of the cornerstone National Environmental Policy Act to spur the construction of highways, pipelines and other infrastructure projects. Environmental activists and lawyers questioned the legality of the move and accused the administration of using the coronavirus pandemic and national unrest to speed up actions that have been moving slowly through the regulatory process”.

British Petroleum says 300,000-500,000 barrels a day are at risk in 2020. Photo: AFP. |

Politics and economics also threaded through many stories of a struggling fossil fuel industry in the context of COVID-19 challenges. For example, in Australia Sydney Morning Herald journalists David Crowe and Mike Foley wrote, “A new wave of spending on energy projects to cut Australia's carbon emissions is on the way under a contentious federal government plan that sidelines coal but highlights gas as a key fuel for the future. Vowing to build on more than $10 billion already spent on clean energy, the Morrison government will name electric vehicles, batteries, renewables and gas as some of the key technologies it will support”. Meanwhile, in the UK BBC reported, “BP has announced plans to cut 10,000 jobs following a global slump in demand for oil because of the coronavirus crisis. The oil giant had paused redundancies during the peak of the pandemic but told staff on Monday that around 15% will leave by the end of the year. BP has not said how many jobs will be lost in the UK but it is thought the figure could be close to 2,000. Chief executive Bernard Looney blamed a drop in the oil price for the cuts”.

Cultural themes also wove through many June climate change or global warming stories. These stories continued to demonstrate that climate change is not merely a single issue that is separate from other important scientific, political, economic, environmental and societal challenges: rather stories depicting cultural facets of climate change illustrate the intersections with pressing interrogations of asymmetrical COVID-19 impacts and with unjust race and class challenges, among others, that affect our shared human society. To illustrate, stories addressed efforts to undermine climate science in federal agencies like the US Environmental Protection Agency. For example, New York Times journalist Lisa Friedman reported that “efforts to undermine climate change science in the federal government, once orchestrated largely by President Trump’s political appointees, are now increasingly driven by midlevel managers trying to protect their jobs and budgets and wary of the scrutiny of senior officials, according to interviews and newly revealed reports and surveys”. She continued, “Government experts said they have been surprised at the speed with which federal workers have internalized President Trump’s antagonism for climate science, and called the new landscape dangerous”.

Protesters march on June 15, 2020 in New York City. Photo: Getty Images.

Furthermore, cultural stories in June 2020 made important links between racism and differential vulnerability to risks and hazards associated with climate change or global warming. In other words, the police killing of George Floyd in the US prompted many re-considerations of historically unequal burdens placed on disadvantaged and marginalized communities by climate changing activities. For example, writing in The Washington Post, climate scientist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson wrote that “the sheer magnitude of transforming our energy, transportation, buildings and food systems within a decade, while striving to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions shortly thereafter, is already overwhelming. And black Americans are disproportionately more likely than whites to be concerned about — and affected by — the climate crisis. But the many manifestations of structural racism, mass incarceration and state violence mean environmental issues are only a few lines on a long tally of threats... I need you to understand that our racial inequality crisis is intertwined with our climate crisis. If we don’t work on both, we will succeed at neither”. As a second example, New York Times journalist Somini Sengupta interviewed three ‘prominent environmental defenders’ about connections between anti-racism and 21st century climate change. She observed, “Racial and economic inequities need to be tackled as this country seeks to recalibrate its economic and social compass in the weeks and months to come. Racism, in short, makes it impossible to live sustainably”.

Thanks for continuing to value our Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) work. We remain committed to updating our 23 open-source datasets, 13 country and seven regional profiles among global newspaper, television and radio assessments for you! If possible, please consider donating to MeCCO by following this link.