Monthly Summaries

Issue 47, November 2020

[DOI]

A Shell refinery in Texas. The company was accused of ‘endless greenwash’ as Twitter users pointed out its contribution to the climate crisis. Photo: Dallas Morning News.

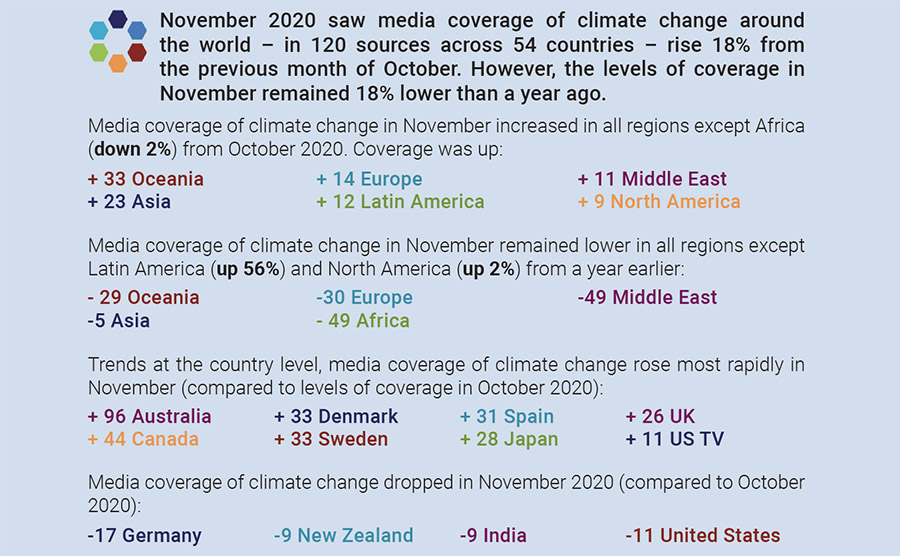

November 2020 saw media coverage of climate change or global warming around the world – in 120 sources across 54 countries – rise 18% from the previous month of October. However, the levels of coverage in November remained 18% lower than a year ago (November 2019). In particular, coverage across international wire services increased 30% from the previous month but was still down 26% from a year earlier. November 2020 coverage across global radio increased 10% from October 2020 and also increased 1% from November 2019. Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through November 2020.

Figure 1. Normalized newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through November 2020.

Coverage in November increased in all regions except Africa (down 2%) from October 2020: coverage was up 33% in Oceania, up 23% in Asia, up 14% in Europe, up 12% in Latin America, up 11% in the Middle East and up 9% in North America. Yet, coverage in November 2020 remained lower in all regions except Latin America (up 56%) and North America (up 2%) from a year earlier (November 2019): coverage was down 49% in both Africa and the Middle East, down 30% in Europe, down 29% in Oceania, and down 5% in Asia.

Among trends at the country level, media coverage of climate change rose most rapidly in November 2020 in Australia (+96%), Canada (+44%), Denmark and Sweden (both +33%), Spain (+31%), Japan (+28%) and the United Kingdom (UK) (+26%) compared to levels of coverage the previous month of October 2020. Trends were mixed in November, however. In contrast, media coverage of climate change or global warming dropped in Germany (-17%), the United States (-11%), New Zealand (-9%) and India (-9%). In our ongoing monitoring of US television sources, November 2020 coverage of climate change or global warming increased 11% from October 2020 but was still 3% lower than levels of coverage in November 2019.

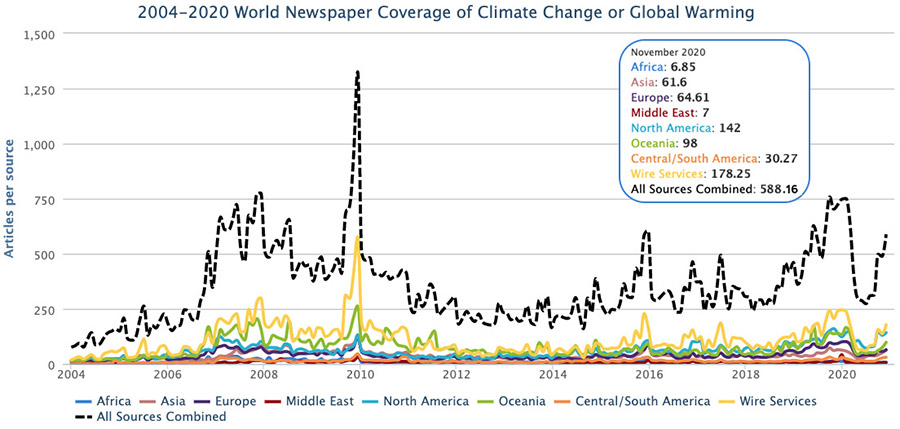

Figure 2. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming on international wire services - The Associated Press, Agence France Presse, The Canadian Press, and United Press International (UPI) – from January 2004 through November 2020.

Villagers wade on flood water brought by a lahar flow due to typhoon Goni at the foot of Mayon volcano in The Philippines. Photo: EPA. |

From the quantity to the quality and content of coverage, ecologicaland meteorological themes continued to dominate news stories connecting events and a changing climate in the month of November like in previous recent months. Throughout November, news of cyclones, typhoons and hurricanes – with stories increasingly making links to a changing climate – punctuated the media landscape.

At the start of November, Super Typhoon Goni along with Typhoon Rolly stirred up international media accounts. For example, correspondent Daisy Dunne from The Independent reported, “It was an apocalypse, a circumstance you can't even imagine. On social media, we saw floating bodies on flash floods,” says Jacques Fallaria, a 19-year-old climate activist from Bulacan, the Philippines. “The situation we are in right now should send proof to our world leaders that climate change is real and institutions should be held accountable for what has just happened in our country”... Scientists have reasoned that the growing intensity of storms is likely linked to the climate crisis. This is because tropical cyclones use warm, moist air as fuel and, as oceans heat up, more of this fuel is becoming available”. Journalist Minerva Newman from The Manila Bulletin reported that “Filipinos that are concerned about the impacts of climate change take actions to prepare for future disasters”.

As the month unfolded, Typhoon Vamco (or Ulysses) then wrought further havoc with 150 mile an hour winds upon landfall. Many news stories drew on this news hook of the fifth major storm in six weeks to impact the Philippines, as it was the seventh over this period to impact Vietnam. For example, Washington Post correspondents Regine Cabato and Miriam Berger reported, “Dozens are dead and whole villages remain underwater three days after Typhoon Vamco slammed into the Philippines, the third typhoon and fifth tropical cyclone to wallop the region in recent weeks... Mahar Lagmay, executive director of the University of the Philippines’ Resilience Institute, cautioned that as the climate crisis worsens and the scale of flooding increases, the government must act by mapping out and communicating these unprecedented threats to residents”.

Meanwhile, in the ongoing Atlantic hurricane season, hurricanes Eta and Iota both caused extensive damage in Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala, also impacting other neighboring countries in Central America and in the Caribbean. As an illustration, reports from the Southern Honduran community of Duyure, Choluteca described damage to homes, a washed out highway and severe crop losses. Many international news accounts made connections during this time between hurricanes and climate change. For example, New York Times journalist Veronica Penney wrote an extensive piece about ‘5 Things We Know about Climate Change and Hurricanes’. As subtropical storm Theta became the 29th named storm of the 2020 hurricane season (a new record for the number of storms), she commented, “Scientists can’t say for sure whether global warming is causing more hurricanes, but they are confident that it’s changing the way storms behave.” As another example, reporting for the Guardian, journalist Jeff Hirst in Honduras commented, “Climate scientists say that this year’s record-breaking hurricane season and the “unprecedented” double blow for Central America has a clear link to the climate crisis…The evidence of the influence of the climate crisis is not so much in the record-breaking 30 tropical storms in the Atlantic so far this year, but the strength, rapid intensification and total rainfall of these weather systems”.

The Eiffel Tower is illuminated in Paris on November 4, 2016, when the Paris climate accord took effect. Photo: Patrick Kovarik/AFP/Getty Images. |

As the month wore in Cyclone Nivar made news as it slammed into Southern India. A subset of the many news reports connected the dots between the storm and climate change. For example, New York Times correspondents Emily Schmall and Hari Kumar reported, “A severe cyclone made landfall in eastern India early Thursday, killing at least three people and lashing coastal areas off the Bay of Bengal with strong winds and heavy rain. Cyclone Nivar, the fourth named storm in the North Indian Ocean this year, struck near Puducherry, a city about 90 miles south of the manufacturing hub of Chennai in the state of Tamil Nadu. The storm weakened significantly on landfall and has continued to weaken as it moved northwest... Cyclones have grown more intense and more frequent across South Asia as climate change has resulted in warmer sea temperatures”.

In November, many political and economic themed media stories about climate change or global warming also were abundant. Beginning the month, the news of the US Trump Administration’s official exit from the United Nations Paris Climate Agreement generated media attention. For example, Washington Post journalists Steven Mufson and Brady Dennis reported, “The exit of the world’s largest economy — and the second biggest emitter of greenhouse gases after China — comes three years to the day after President Trump began the drawn-out legal process of withdrawing the nation from the 2015 Paris climate accord. But whether the U.S. exit turns out to be brief or lasting depends on the outcome of the presidential contest. A second Trump term would make clear that an international effort to slow the Earth’s warming will not include the U.S. government. Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, meanwhile, has vowed to rejoin the Paris accord as soon as he is inaugurated, and to make the United States a global leader on climate action”. Furthermore, Associated Press correspondent Seth Borenstein noted, “What happens on election day will to some degree determine how much more hot and nasty the world’s climate will likely get, experts say”.

A few days later, Bloomberg journalist Jennifer A. Dlouhy wrote in The Washington Post, “Even with the involvement of the U.S., the world’s second-largest producer of carbon dioxide emissions, the global response to climate change faced an uphill battle. Then President Donald Trump pulled the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement on global warming. The threat of climate change presented one of the starkest contrasts between Trump and Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential race. Now, after winning the election, Biden will get a chance to see through his pledge to sign the U.S. back into the Paris accord as soon as he can”.

Photo: Demetrius Freeman, The Washington Post. |

These stories emerged against an uncertain backdrop of a still uncertain US Presidential Election result. In contrast to the Trump Administration stance, the now-President Elect Joe Biden promised to rejoin the Paris Agreement on his first day in office (January 20, 2021). Stories threaded these considerations together in a blanket of uncertainty, worry and woe. For example, on November 4th BBC journalist Matt McGrath reported, “After a three-year delay, the US has become the first nation in the world to formally withdraw from the Paris climate agreement. President Trump announced the move in June 2017, but UN regulations meant that his decision only takes effect today, the day after the US election. The US could re-join it in future, should a president choose to do so”. Meanwhile, Associated Press journalists Frank Jordans and Seth Borenstein noted, “The move, long threatened by U.S. President Donald Trump and triggered by his administration a year ago, further isolates Washington in the world but has no immediate impact on international efforts to curb global warming. Still, the U.N. agency that oversees the treaty, France as the host of the 2015 Paris talks and three countries currently chairing the body that organizes them — Chile, Britain and Italy — issued a joint statement expressing regret at the U.S. withdrawal”.

The eventual win of the US election by President-elect Joe Biden and Vice President-elect Kamala Harris then led to stories of transition teams and appointments and their relationship to concerted climate policy action. For example, the day after the election was decided (November 7th) Washington Post journalists Juliet Eilperin, Dino Grandoni and Darryl Fears reported, “Joe Biden, the projected winner of the presidency, will move to restore dozens of environmental safeguards President Trump abolished and launch the boldest climate change plan of any president in history. While some of Biden’s most sweeping programs will encounter stiff resistance from Senate Republicans and conservative attorneys general, the United States is poised to make a 180-degree turn on climate change and conservation policy. Biden’s team already has plans on how it will restrict oil and gas drilling on public lands and waters; ratchet up federal mileage standards for cars and SUVs; block pipelines that transport fossil fuels across the country; provide federal incentives to develop renewable power; and mobilize other nations to make deeper cuts in their own carbon emissions. In a victory speech Saturday night, Biden identified climate change as one of his top priorities as president, saying Americans must marshal the “forces of science” in the “battle to save our planet”.

As another example, a few days later New York Times correspondents Michael D. Shear and Lisa Friedman noted, “President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr. is poised to unleash a series of executive actions on his first day in the Oval Office, prompting what is likely to be a years long effort to unwind President Trump’s domestic agenda and immediately signal a wholesale shift in the United States’ place in the world. In the first hours after he takes the oath of office on the West Front of the Capitol at noon on Jan. 20, Mr. Biden has said, he will send a letter to the United Nations indicating that the country will rejoin the global effort to combat climate change, reversing Mr. Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris climate accord with more than 174 countries”.

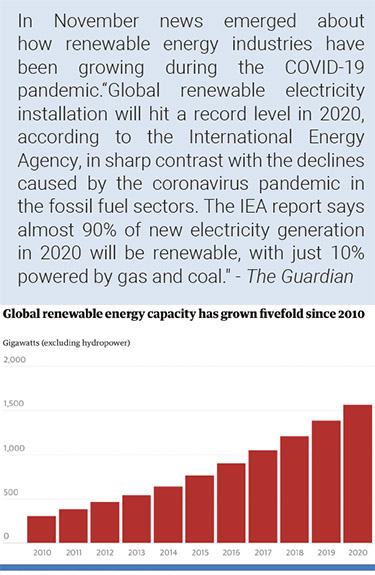

Guardian Graphic. Source: IEA. |

Meanwhile, in November news emerged about how renewable energy industries have been growing during the COVID-19 pandemic as fossil fuel industries have faced waning demand. Many stories related these developments to climate change. For example, Guardian correspondent Damian Carrington reported, “Global renewable electricity installation will hit a record level in 2020, according to the International Energy Agency, in sharp contrast with the declines caused by the coronavirus pandemic in the fossil fuel sectors. The IEA report published on Tuesday says almost 90% of new electricity generation in 2020 will be renewable, with just 10% powered by gas and coal. The trend puts green electricity on track to become the largest power source in 2025, displacing coal, which has dominated for the past 50 years. Growing acceptance of the need to tackle the climate crisis by cutting carbon emissions has made renewable energy increasingly attractive to investors. The IEA reports that shares in renewable equipment makers and project developers have outperformed most major stock market indices and that the value of shares in solar companies has more than doubled since December 2019”.

Related to COVID-19 and renewable energy news, many stories in November picked up on the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s release of his Green Industrial Revolution recovery plan. For example, journalist Roger Harrabin from BBC reported, “New cars and vans powered wholly by petrol and diesel will not be sold in the UK from 2030, Prime Minister Boris Johnson has said. But some hybrids would still be allowed, he confirmed. It is part of what Mr Johnson calls a "green industrial revolution" to tackle climate change and create jobs in industries such as nuclear energy. Critics say the £4bn allocated to implement the 10-point plan is far too small for the scale of the challenge. The total amount of new money announced in the package is a 25th of the projected £100bn cost of high-speed rail, HS2”. Meanwhile, Guardian correspondents Peter Walker and Jessica Elgot commented, “Boris Johnson has announced plans for the government’s self-styled green industrial revolution, bringing praise from environmental groups but also questions about the scale of new funding, and the planned expansion of nuclear and hydrogen power. In a move aimed at retaking the initiative after a politically turbulent few weeks, the prime minister said the 10-point plan would create up to 250,000 jobs, with much of the focus aimed at the north of England, Midlands, Scotland and Wales”.

Figure 3. Front pages of The Daily Mail, The Daily Telegraph and The Times in the days following the UK Prime Minister’s ‘Green Industrial Revolution’ announcement in November 2020.

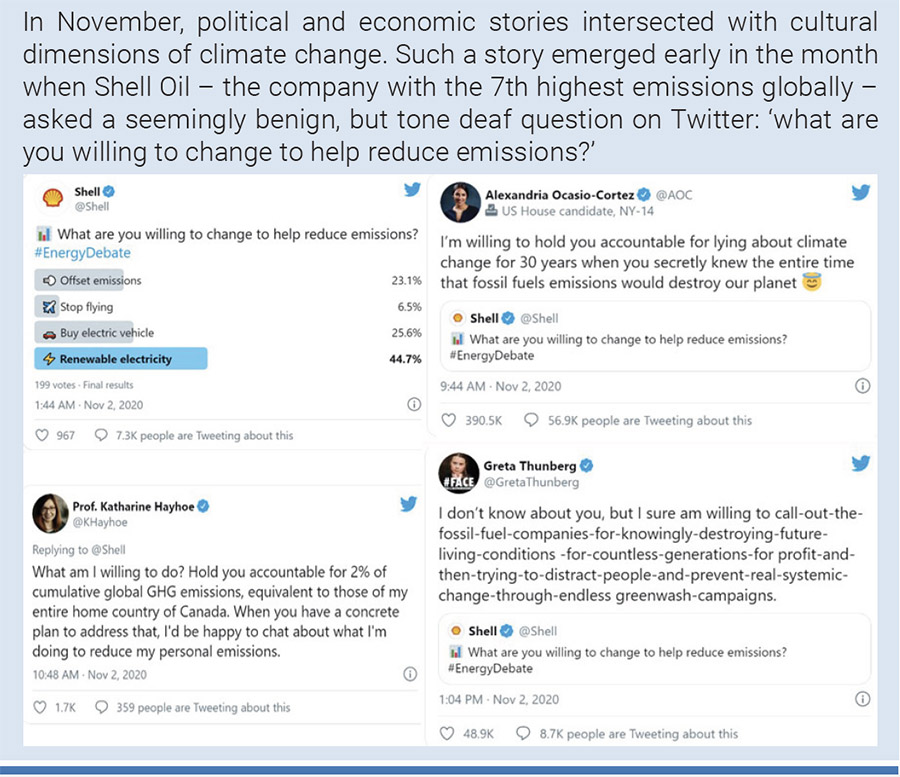

In November, political and economic stories intersected with cultural dimensions of climate change. Such a story emerged early in the month when Shell Oil – the company with the 7th highest emissions globally – asked a seemingly benign, but tone deaf question on Twitter: ‘what are you willing to change to help reduce emissions?’ That casting of the challenge onto individuals sparked immediate replies. These exchanges on social media were then covered in newspaper, TV and radio reports. For example, Guardian correspondent Damian Carrington reported, “A climate poll on Twitter posted by Shell has backfired spectacularly, with the oil company accused of gas lighting the public. The survey, posted on Tuesday morning, asked: “What are you willing to change to help reduce emissions?” Though it received a modest 199 votes the tweet still went viral – but not for the reasons the company would have hoped. The US congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was one high-profile respondent, posting a tweet that was liked 350,000 times...Greta Thunberg accused the company of “endless greenwash”, while the climate scientist Prof Katharine Hayhoe pointed out Shell’s huge contribution to the atmospheric carbon dioxide that is heating the planet. Shell then hid her reply, she said. Another climate scientist, Peter Kalmus, was more direct, and said the company was gas lighting the public by suggesting individual actions could stop the climate crisis, rather than systemic change to the fossil fuel industry. Some Twitter users saw irony in this, while others asked if the company was “out of its mind”. And continuing with critiques, The Daily Mirror called the plan “more style than substance”.

Figure 4. Shell Oil’s initial Tweet followed by three selected responses.

Also, on the heels of the US Presidential election, various social movements noted their roles in raising visibility of climate and environment issues as well as contributing to the victory of Joe Biden. For example, Guardian journalist Oliver Milman reported on the Sunrise Movement, noting “Joe Biden will have to navigate a path for the most ambitious climate agenda ever adopted by a US president through not only stubborn Republican obstruction but also an emergent youth climate movement that is already formulating plans to hold him to account”.

There were also many media stories about scientific research and findings about aspects of climate change or global warming in November. Prominently among them was media coverage of a study published in Nature that found that “warmer sea surface temperatures induce a slower decay by increasing the stock of moisture that a hurricane carries as it hits land” and “as the world continues to warm, the destructive power of hurricanes will extend progressively farther inland”. As an example of media attention and discussion, Associated Press journalist Seth Borenstein reported that the study “looked at 71 Atlantic hurricanes with landfalls since 1967. It found that in the 1960s, hurricanes declined two-thirds in wind strength within 17 hours of landfall. But now it generally takes 33 hours for storms to weaken that same degree”. Borenstein also noted that the study found that “warmer ocean waters from climate change are likely making hurricanes lose power more slowly after landfall, because they act as a reserve fuel tank for moisture”.

Despite the fall off in airline and other transportation, CO2 levels are on the rise. Photo: Getty Images. |

In mid-November, a World Meteorological Organization report – noting that greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere reached 410.5 parts per million – garnered considerable media attention. For example, BBC journalist Matt McGrath reported, “The global response to the Covid-19 crisis has had little impact on the continued rise in atmospheric concentrations of CO2...This year carbon emissions have fallen dramatically due to lockdowns that have cut transport and industry severely. But this has only marginally slowed the overall rise in concentrations”. Meanwhile, Guardian correspondent Damian Carrington noted, “There is estimated to have been a cut in emissions of between 4.2% and 7.5% in 2020 due to the shutdown of travel and other activities. But the WMO said this was a “tiny blip” in the continuous buildup of greenhouse gases in the air caused by human activities, and less than the natural variation seen year to year”.

In late November, a study in Science magazine – that found that trees are counterintuitively dropping their leaves earlier in a warmer climate – sparked many media stories. For example US National Public Radio host Ari Shapiro reported, “Constantin Zohner is a climate change biologist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. And he says the effects of global warming - hotter temperatures deeper into the year - led scientists to predict that trees would drop their leaves weeks later by the end of this century. Now his team says the opposite may be true. Writing in the journal Science, they say leaves may actually fall a few days earlier in the future. And the reason...climate change”. As a second example, CNN correspondent Amy Woodyatt noted, “Trees will start to shed their leaves earlier as the planet warms, a new study has suggested, contradicting previous assumptions that warming temperatures are delaying the onset of fall. Every year, in a process known as senescence, the leaves of deciduous trees turn yellow, orange and red as they suspend growth and extract nutrients from foliage, before falling from the tree ahead of winter. Leaf senescence also marks the end of the period during which plants absorb carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. Global warming has resulted in longer growing seasons -- spring leaves are emerging in European trees about two weeks earlier, compared with 100 years ago, researchers said”.

We in the Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) remain here for you, committed to our work monitoring media coverage of these intersecting dimensions and themes associated with climate change in this year 2020. That said, our ongoing work is dependent on financial support so your support – in any amount – is deeply appreciated. Follow this link to contribute to our ongoing efforts: https://giving.cu.edu/fund/media-and-climate-change-observatory-mecco.