Monthly Summaries

Issue 48, December 2020

[DOI]

Winds carry plumes of smoke in Russia, center right, toward the southwest, mixing with a swirling storm system. Photo: Joshua Stevens/NASA Earth Observatory/AP.

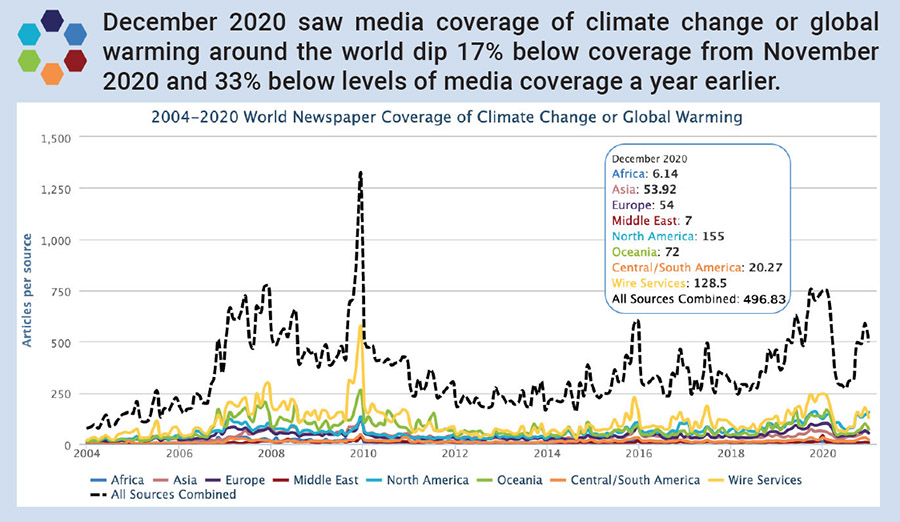

December 2020 saw media coverage of climate change or global warming around the world dip 17% below coverage from November 2020 and 33% below levels of media coverage a year earlier (December 2019). Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through December 2020.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through December 2020.

Decreased media attention to climate change or global warming was evident in eight of the 13 countries we in the Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) monitor monthly: the exceptions with increasing coverage compared to November 2020 were Canada (up 37%), Denmark (up 25%), India (up 12%), Russia (up 92%) and Sweden (up 25%). Higher levels of Canadian media coverage of climate change also led to an increase in North American coverage from November 2020 (up 9%) even though US newspaper coverage dropped 18%.

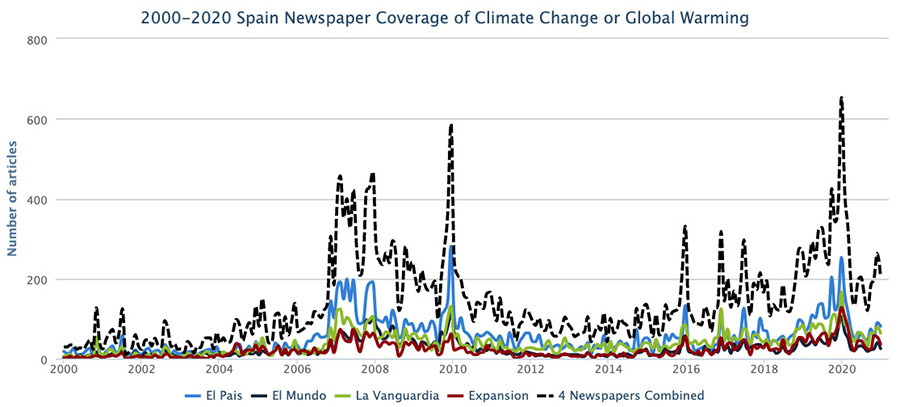

Otherwise, media coverage of climate change or global warming decreased across global radio (-24%) and wire services (-28%) as well as in Africa (-3%), Asia (-24%), Europe (-16%), Latin America (-33%), the Middle East (-16%), and Oceania (-27%). Furthermore, coverage was down in Australia (-25%), Germany (-13%), Japan (-2%), New Zealand (-30%), Norway (-11%), Spain (-22%) (see Figure 2), the United Kingdom (UK) (-27%), the United States (US) newspapers (-18%) and US television (-38%).

Figure 2. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in Spain – El País, El Mundo, La Vanguardia, and Expansión – from January 2004 through December 2020.

From the quantity to the quality and content of coverage, many political and economic themed media stories emerged in December about climate change or global warming. To begin, in early December fourteen countries committed to reducing shipping emissions, increasing offshore renewable capacity and other issues relating to ocean sustainability. The climate change-related dimensions of these commitments earned coverage. For example, Guardian environment correspondent Fiona Harvey reported, “Governments responsible for 40% of the world’s coastlines have pledged to end overfishing, restore dwindling fish populations and stop the flow of plastic pollution into the seas in the next 10 years. The leaders of the 14 countries set out a series of commitments on Wednesday that mark the world’s biggest ocean sustainability initiative, in the absence of a fully-fledged UN treaty on marine life. The countries – Australia, Canada, Chile, Fiji, Ghana, Indonesia, Jamaica, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Namibia, Norway, Palau and Portugal – will end harmful subsidies that contribute to overfishing, a key demand of campaigners. They will also aim to eliminate illegal fishing through better enforcement and management, and to minimise bycatch and discards, as well as implementing national fisheries plans based on scientific advice. Each of the countries, members of the High Level Panel for Sustainable Ocean Economy, has also pledged to ensure that all the areas of ocean within its own national jurisdiction – known as exclusive economic zones – are managed sustainably by 2025. That amounts to an area of ocean roughly the size of Africa”.

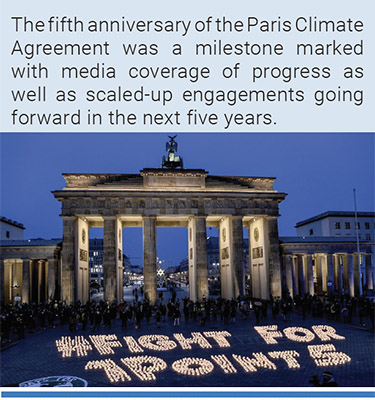

Activists light candles showing the slogan 'Fight For 1 Point 5' in front of the Brandenburg Gate on the occasion of the fifth anniversary of the signing of the Paris Climate Agreement, in Berlin on December 11, 2020. Photo: Britta Pedersen/dpa via AP. |

Also in early December, the fifth anniversary of the Paris Climate Agreement was a milestone marked with media coverage of progress as well as scaled-up engagements going forward in the next five years. For example, Korea Times reporters Frank Rijsberman and Ingvild Solvang commented, “As 2020 comes to a close, the date is fast approaching for all parties to the Paris Climate Agreement to submit their updated commitments, or NDCs that specifically delineate how each country will meet the common climate goals within the United Nations framework. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, COP26 climate talks were postponed to 2021, and instead a series of virtual events including the Climate Ambition Summit was held on Dec. 12, where countries could give updates on their adjusted NDCs. Much has happened in recent months. While the Republic of Korea did not show very ambitious NDC targets earlier this year, President Moon Jae-in announced net zero ambitions for 2050”. As another example, Associated Press reporters Frank Jordans and Jeff Schaeffer observed, “U.S. President-elect Joe Biden pledged Saturday to rejoin the Paris climate accord on the first day of his presidency, as world leaders staged a virtual gathering to celebrate the fifth anniversary of the international pact aimed at curbing global warming. Heads of state and government from over 70 countries took part in the event — hosted by Britain, France, Italy, Chile and the United Nations — to announce greater efforts in cutting the greenhouse gas emissions that fuel global warming. The outgoing administration of President Donald Trump, who pulled Washington out of the Paris accord, wasn’t represented at the online gathering. But in a written statement sent shortly before it began, Biden made clear the U.S. was waiting on the sidelines to join again and noted that Washington was key to negotiating the 2015 agreement, which has since been ratified by almost all countries around the world”.

Meanwhile, Guardian journalist Fiona Harvey noted, “The world is still not on track to fulfil the 2015 Paris climate agreement, the UK’s business secretary Alok Sharma warned, after a summit of more than 70 world leaders on the climate crisis ended with few new commitments on greenhouse gas emissions”. Furthermore, Independent journalist Daisy Dunne “asked scientists, politicians and activists from across the world to describe what they would like to see happen within the next five years to see the world shift to be in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement”. And Daily Star (Lebanon) journalists Jitendra Joshi, Anna Malpas and Patrick Galey wrote, “UN chief Antonio Guterres on Saturday urged world leaders to declare a "state of climate emergency" and shape greener growth after the coronavirus pandemic, as he opened a summit marking five years since the landmark Paris Agreement. The Climate Ambition Summit, being held online, comes as the United Nations warns current commitments to tackle rises in global temperatures are inadequate. The commitments made in Paris in 2015 were "far from enough" to limit temperature rises to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the UN secretary-general said in his opening address to the summit, which is co-hosted by Britain and France”.

Protesters gathered outside ExxonMobil's annual shareholder meeting in May 2019. Photo: 350.org/CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. |

Also in December, ExxonMobil declared its intent to reduce greenhouse gas emissions intensity. Descriptive accounts as well as sharp critiques about these commitments – short of clear decarbonization promises – were pervasive in media accounts of this declaration. For example, journalist Christopher M. Matthews from The Wall Street Journal reported, “Exxon Mobil Corp pledged to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions from its operations over the next five years and eliminate routine flaring of methane by 2030, responding to pressure from activists and investors to lower its carbon footprint. The Texas-based oil giant said Monday that it would cut the “intensity” of emissions from its oil-and-gas production by 15% to 20% by 2025. It didn’t provide hard numbers on exactly how much of total emissions those reductions would represent. The company also said it would end routine flaring, or burning, of methane from its oil-and-gas operations in the next 10 years. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas that, like carbon dioxide, contributes to climate change, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. The targets are related to emissions that come directly from Exxon’s operations and not from its products, like gasoline and jet fuel. Exxon said it would begin disclosing emissions data related to its products next year”. Meanwhile, CNBC reporter Eric Rosebaum noted, “A week after multiple activist investor groups targeted Exxon Mobil for recent financial underperformance as well as climate change concerns, the oil giant has released a new five-year plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The company stressed that the plan has been in the works for months — its previous five-year plan through 2020 is drawing to a close — but it also noted in outlining new carbon goals that the plan ″includes input from shareholders”.

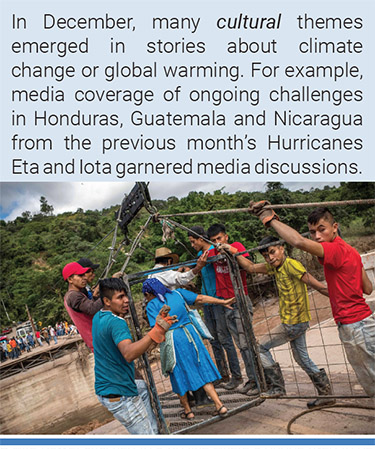

In December, many cultural themes emerged in stories about climate change or global warming. For example, media coverage of ongoing challenges in Honduras, Guatemala and Nicaragua from the previous month’s Hurricanes Eta and Iota garnered media discussions. For example, Washington Post journalist Kevin Sieff reported, “Weeks after Hurricanes Eta and Iota struck Central America in quick succession, nearly 100,000 Hondurans are living in shelters, many of which have become coronavirus hotspots. The country’s economy has been paralyzed. It is an unprecedented crisis, Honduran President, Juan Orlando Hernández said in an interview with The Washington Post on Friday. Hernández warned that in the absence of a coordinated international response, migration from Honduras to the United States could surge... Hernández and several other senior Honduran officials visited Washington this week to lobby for a humanitarian assistance package from multilateral organizations such as the World Bank and from the U.S. government. He stressed the link between the hurricanes and climate change, suggesting that wealthier countries that emit more greenhouse gases have a debt to pay in the recovery effort”.

A wire basket attached to a zip line where a bridge used to be in Jocotán, Guatemala. Photo: Daniele Volpe, New York Times. |

New York Times correspondent Natalie Kitroeff added, “Already crippled by the coronavirus pandemic and the resulting economic crisis, Central America is now confronting another catastrophe: The mass destruction caused by two ferocious hurricanes that hit in quick succession last month, pummeling the same fragile countries, twice. The storms, two of the most powerful in a record-breaking season, demolished tens of thousands of homes, wiped out infrastructure and swallowed vast swaths of cropland. The magnitude of the ruin is only beginning to be understood, but its repercussions are likely to spread far beyond the region for years to come. The hurricanes affected more than five million people — at least 1.5 million of them children — creating a new class of refugees with more reason than ever to migrate. Officials conducting rescue missions say the level of damage brings to mind Hurricane Mitch, which spurred a mass exodus from Central America to the United States more than two decades ago... If the devastation does set off a new wave of immigration, it would test an incoming Biden administration that has promised to be more open to asylum seekers, but may find it politically difficult to welcome a surge of claimants at the border. In Guatemala and Honduras, the authorities readily admit they cannot begin to address the misery wrought by the storms. Leaders of both countries last month called on the United Nations to declare Central America the region most affected by climate change, with warming ocean waters making many storms stronger and the warmer atmosphere making rainfall from hurricanes more ruinous”.

In December, the death of a 9-year-old UK citizen named Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah from ‘exposure to air pollution’ generated media attention who made links to climate change. For example, CBS News journalist Haley Ott reported, “Air pollution "made a material contribution" to the death of nine-year-old London schoolgirl Ella Kissi-Debrah, a U.K. coroner ruled on Wednesday. The landmark ruling is the first time air pollution has been officially listed as a cause of death for anyone in the U.K. Ella Kissi-Debrah died in 2013 after suffering severe asthma attacks for three years... When she died, the cause of her death was determined to be a severe asthma attack leading to respiratory failure. But a report compiled for Kissi-Debrah by Stephen Holgate, the former chair of the U.K. government's advisory committee on air pollution and a professor at Britain's University of Southampton, found that Ella's asthma attacks coincided with years of illegal air pollution levels on a busy street near her home”. Meanwhile, Guardian correspondent Sandra Laville noted, “Until now, the statistics on air pollution deaths have been presented in black and white – numbers on a page that estimate between 28,000 and 36,000 people will die as a result of toxic air pollution every year in the UK. But the life and death of nine-year-old Ella Kissi-Debrah is in full colour: from the pictures of her wearing her gymnastics leotard hung with medals, to the image of her mother and siblings holding aloft her photograph, when they no longer had her to hold on to, as they campaigned for the truth”.

Furthermore, ecological and meteorological dimensions of climate change and global warming were evident in December media accounts. Early in December, the European Commission Copernicus Climate Change Service announced that the planet’s average November 2020 temperatures were hotter than any previous November on record. This sparked media coverage. For example, CNN journalist Emma Reynolds reported, “The world just experienced its hottest November on record while Europe had its warmest fall, according to an alarming report from the European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service. Temperatures were most elevated in a large region across northern Europe, Siberia and the Arctic Ocean, where sea ice was at the second lowest level ever seen in November. The United States, South America, southern Africa, the Tibetan Plateau, eastern Antarctica and most of Australia also saw temperatures well above average. Globally, November was almost 0.8 degrees Celsius (33.4 Fahrenheit) above the average for 1981-2010, and 0.1C (32.2F) higher than last year. And this unusual heat comes despite the cooling effect of La Niña. In Australia, a bushfire has been burning out of control for six weeks now in the popular tourist spot of Fraser Island as parts of the country swelter through a record-breaking heatwave”.

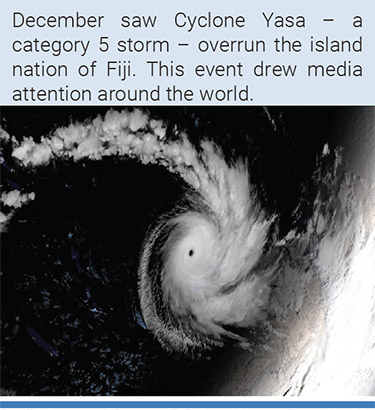

Satellite image of Category 5 Cyclone Yasa on December 16, 2020 as it neared Fiji. Credit: CIRA/RAMMB. |

Meanwhile, December saw Cyclone Yasa – a category 5 storm – overrun the island nation of Fiji. This event drew media attention around the world. For example, Washington Post journalist Andrew Freedman reported, “Tropical Cyclone Yasa, currently the strongest storm on Earth, is headed for a potentially devastating landfall in Fiji within the next 24 hours. The storm is now packing sustained winds estimated at 160 miles per hour, which makes it the equivalent of a Category 5 storm. It threatens to cause damage on the scale of Tropical Cyclone Winston, which caused widespread destruction when it hit in 2016... Fiji is viewed as especially vulnerable to the ravages of climate change, particularly through sea level rise and extreme weather events such as tropical cyclones. On Dec. 11, the U.N. Environment Program named him a “champion of the Earth” for his efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions and negotiate global climate agreements. The country was the first to ratify the Paris climate accord, according to the program, and is trying to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050”.

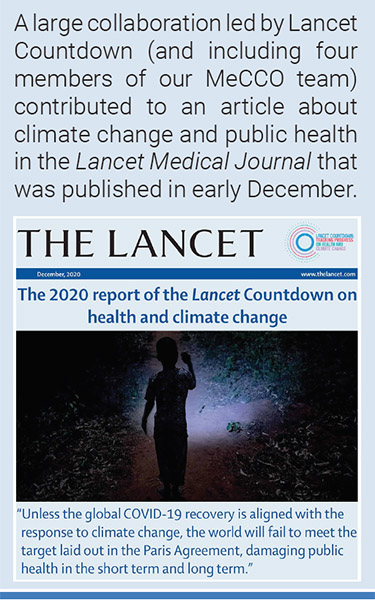

In December, there were also many media stories about scientific research and findings about aspects of climate change or global warming. To begin, a large collaboration led by Lancet Countdown (and including four members of our MeCCO team) contributed to an article about climate change and public health in the Lancet Medical Journal that was published in early December. This report generated widespread media attention. For example, Sydney Morning Herald journalist Mary Ward reported, “Medical organisations say Australia is lagging behind other countries when it comes to tackling the health impacts of climate change and warn inaction is putting lives at risk. According to the MJA-Lancet Countdown report, an annual assessment of the country's progress on health outcomes related to climate change, Australians' exposure to the health effects of events such as bushfires and heatwaves is increasing”. As another example, Guardian correspondent Natalie Grover noted, “The devastation caused by Covid-19 presents an opportunity for countries to rebuild their economies in a way that is environmentally responsible, researchers say... The 2020 report – compiled by experts from more than 35 institutions including the World Health Organization and the World Bank, and led by University College London (UCL) – teases out parallels between infectious diseases such as Covid-19 and climate change, highlighting that climate change and its fossil fuel-powered drivers such as urbanisation and intensive agriculture tend to encroach upon wildlife habitats, thereby encouraging pathogens to jump from animals into humans. As the catastrophic experience of Covid-19 spurs measures to reduce the risk of future pandemics, prioritising action on the climate crisis will be critical to achieving that goal”. Meanwhile, journalist Catherine Clifford from NBC reported, “according to The Lancet report, where people live and how much money they have directly effects their capacity to resist threats to their health from climate change”. And, Expressen (Sweden) journalist Adam Koskelainen reported on how human’s public health are impacted by changes in the climate.

|

In mid-December, new United Nations (UN) reports on the state of planet Earth caught the attention of multiple media outlets. The UN Climate report entitled ‘2020 on track to be one of three warmest years on record’ made news in multiple outlets around the globe. For example, Washington Post journalist Andrew Freedman reported, “This year will be one of the three hottest on record for the globe, as marine heat waves swelled over 80 percent of the world’s oceans, and triple-digit heat invaded Siberia, one of the planet’s coldest places. These troubling indicators of global warming are laid out in a U.N. State of the Climate report published Wednesday. To mark the report’s release and to build momentum toward new climate action under the Paris accord, U.N. Secretary General António Guterres summarized the findings in unusually stark terms. “To put it simply,” he said in a speech at Columbia University, “the state of the planet is broken””.

Another report – named ‘Emissions Gap’ – from the UN Environmental Program warned of troubling trends and emissions reductions ambitions not meeting the scale of climate change challenges. Media represented this report in several media outlets. For example, Washington Post journalists Brady Dennis, Chris Mooney and Sarah Kaplan reported, “The world’s wealthy will need to reduce their carbon footprints by a factor of 30 to help put the planet on a path to curb the ever-worsening impacts of climate change, according to new findings published Wednesday by the United Nations Environment Program. Currently, the emissions attributable to the richest 1 percent of the global population account for more than double those of the poorest 50 percent. Shifting that balance, researchers found, will require swift and substantial lifestyle changes, including decreases in air travel, a rapid embrace of renewable energy and electric vehicles, and better public planning to encourage walking, bicycle riding and public transit. But individual choices are hardly the only key to mitigating the intensifying consequences of climate change. Wednesday’s annual “emissions gap” report, which assesses the difference between the world’s current path and measures needed to manage climate change, details how the world remains woefully off target in its quest to slow the Earth’s warming. The drop in greenhouse gas emissions during this year’s pandemic, while notable, will have almost no impact on slowing the warming that lies ahead unless humankind drastically alters its policies and behavior, the report finds. Instead, nations would need to “roughly triple” their current emissions-cutting pledges to limit the Earth’s warming to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above the preindustrial average — a central aim of the Paris climate agreement. To reach the loftier goal of holding warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), the report found, countries would need to increase their targets at least fivefold. That goal in particular would require rapid and profound changes in how societies travel, produce electricity and eat”.

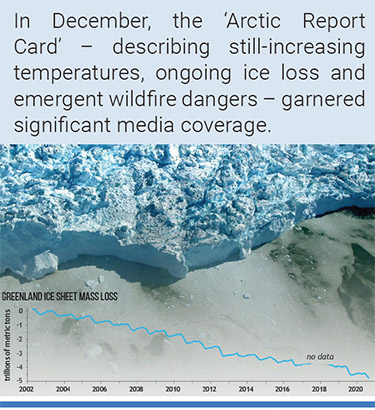

Source: NOAA Climate.gov, adapted from ARC 2020. |

Also in December, the ‘Arctic Report Card’ – describing still-increasing temperatures, ongoing ice loss and emergent wildfire dangers – garnered significant media coverage. For example, Business Day (South Africa) journalist Yereth Rosen reported, “The Arctic region has had its second-warmest year since 1900, continuing a pattern of extreme heat, ice melt and environmental transformation at the top of the world”. Meanwhile, Associated Press journalist Christina Larson noted, “This year’s vast wildfires in far northeastern Russia were linked to broader changes in a warming Arctic, according to a report Tuesday by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Wildfires are a natural part of many boreal ecosystems. But the extent of flames during the 2020 fire season was unprecedented in the 2001-2020 satellite record, and is consistent with the predicted effects of climate change, said Alison York, a University of Alaska Fairbanks fire scientist and a contributor to the annual Arctic Report Card. The recent wildfires were exacerbated by elevated air temperatures and decreased snow cover on the ground in the Arctic region, the report found. The past year — from October 2019 to September 2020 — was the second warmest on record in the Arctic, the report said. And the extent of snow on the ground in June across the Eurasian Arctic was the lowest recorded in 54 years”.

Finally, findings in Earth Systems Science Data journal that global carbon dioxide emissions reductions of 7% in 2020 (due overwhelmingly to reduced travel during the COVID-19 pandemic) were a short-term reduction as infrastructure and systems remain dependent on fossil fuels. This paper earned widespread media accounts. For example, BBC correspondent Matt McGrath reported, “this year saw carbon emissions decline by 2.4 billion tonnes... In contrast, the fall recorded in 2009 during the global economic recession was just half a billion tonnes, while the ending of World War Two saw emissions fall by under one billion tonnes. Across Europe and the US, the drop was around 12% over the year, but some individual countries declined by more. France saw a fall of 15% and the UK went down by 13%... Researchers believe that dramatic drop experienced through the pandemic response might be hiding a longer term fall-off in carbon, more related to climate policies. The annual growth in global CO2 emissions fell from around 3% in the early years of this century to around 0.9% in the 2010s. Much of this change was down to a move away from coal as an energy source” and “While 2020's fall of over two billion tonnes of CO2 is welcome, the scientists say that meeting the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement will need cuts of up to two billion tonnes every year for the next decade”.

2021, we made it! We in the Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) remain here for you, committed to our work monitoring media coverage of these intersecting dimensions and themes associated with climate change. Follow this link to contribute to our ongoing efforts: https://giving.cu.edu/fund/media-and-climate-change-observatory-mecco.