Monthly Summaries

Issue 63, March 2022

[DOI]

Dominika Zarzycka / Getty Images.

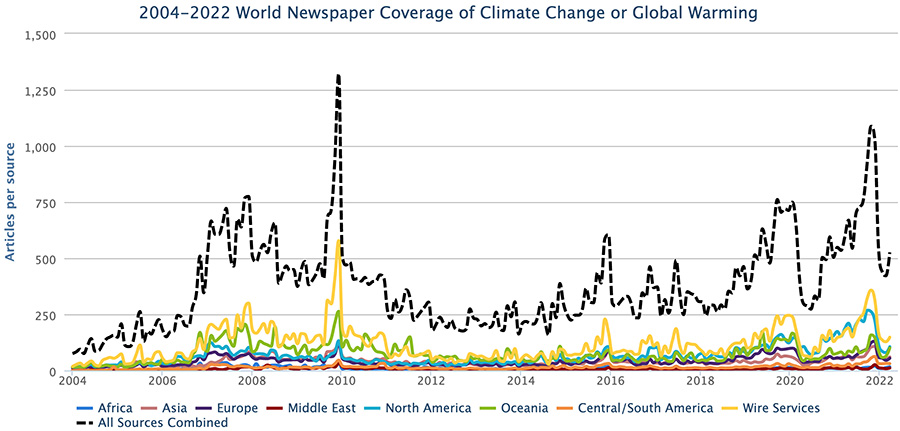

March media attention to climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe increased 19% from February 2022. However, coverage decreased 7% from a year before (March 2021). Meanwhile, March 2022 global radio coverage of climate change or global warming dipped again from the previous month, this time is was down 2%. Meanwhile, coverage in international wire services increased 14% from February 2022. Compared to the previous month coverage bounced back and increased in all regions except Latin America (-4%): Asia (+14%), Europe (+17%), Africa (+19%), North America (+24%), the Middle East (+26%), and Oceania (+36%). Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through March 2022.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through March 2022.

At the country level, United States (US) print coverage increased 22% while television coverage actually dropped 10% from the previous month. Looking at each print outlet, coverage increased 9% in The Washington Post, while The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal both increased 21%, there was an increase of 31% in The Los Angeles Times and there was a jump of 162% in USA Today. Looking at each television outlet, it was a more mixed picture: coverage on Fox News was up 16% while it increased 40% on PBS while doubling on CBS and quintupling on NBC (after a steep drop in February. Meanwhile, coverage decreased on ABC and MSNBC 21%, and 59% on CNN.

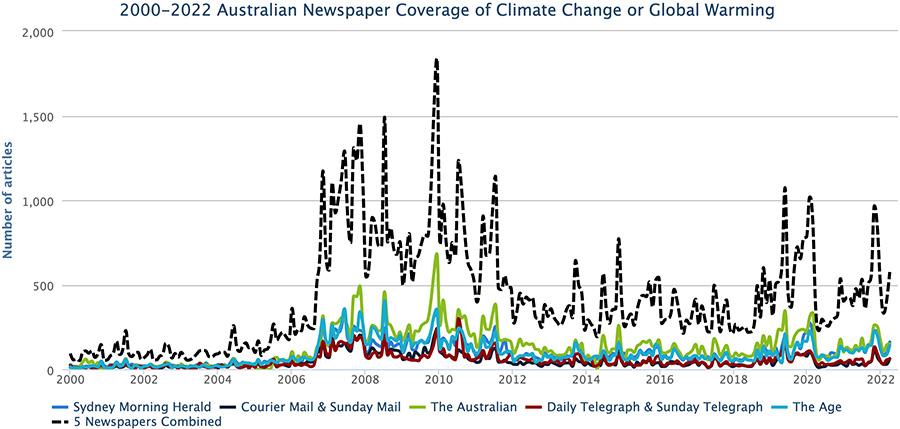

Meanwhile, compared to the previous month, coverage decreased in Russia (-57%). But, among the rest of the countries that we at the Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) monitor, coverage increased from February everywhere else: Japan (+5%), Denmark (+8%), Finland (+10%), Germany (+12%), Spain (+19%), India (+22%), Australia (+23%), the United Kingdom (UK) (+29%), Norway (+42%), Sweden (+47%), Canada (+61%), and New Zealand (+115%).

Figure 2. Australian newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming from January 2000 through March 2022.

Many climate change or global warming stories focused on scientific themes in the month of March. To begin the month, a new study on increased pollen levels and a longer allergy season – with links to climate change – generated several news stories. For example, Associated Press reporter Seth Borenstein (appearing on ABC News) noted, “Climate change has already made allergy season longer and pollen counts higher, but you ain’t sneezed nothing yet. Climate scientists at the University of Michigan looked at 15 different plant pollens in the United States and used computer simulations to calculate how much worse allergy season will likely get by the year 2100. It’s enough to make allergy sufferers even more red-eyed. As the world warms, allergy season will start weeks earlier and end many days later — and it'll be worse while it lasts, with pollen levels that could as much as triple in some places, according to a new study Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications. Warmer weather allows plants to start blooming earlier and keeps them blooming later. Meanwhile, additional carbon dioxide in the air from burning fuels such as coal, gasoline and natural gas helps plants produce more pollen, said study co-author Allison Steiner, a University of Michigan climate scientist. It's already happening. A study a year ago from different researchers found that from 1990 to 2018, pollen has increased and allergy season is starting earlier, with much of it because of climate change. Allergists say that pollen season in the U.S. used to start around St. Patrick’s Day and now often starts around Valentine’s Day. The new study found that allergy season would stretch even longer and the total amount of pollen would skyrocket. How long and how much depends on the particular pollen, the location and how much greenhouse gas emissions are put in the air”.

Yet in March, Russia's invasion of Ukraine limited print newspapers from publishing the results of IPCC Working Group II that was released on the final day of February. Some newspaper coverage around the world addressed it. For example, Spain is one of the European countries most vulnerable to global warming. Climate change will generate 8,000 deaths a year from extreme heat in this country. The journalist Teresa Guerrero narrated in El Mundo, “According to the IPCC, crop losses due to drought and extreme heat have tripled across Europe in the last 50 years and are projected to increase with continued warming, with most of these losses occurring in southern Europe, as the most suitable agricultural areas will move north. Droughts cost Spain already annual losses of around 1,500 million euros.”

Further into March, a publication in Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences entitled ‘Tripling of western US particulate pollution from wildfires in a warming climate’ grabbed news attention. For example, CNN journalist Rachel Ramirez reported, “Only a few months into 2022 and it’s already a dreadful year for wildfires. More than 14,781 separate wildfires have scorched over half a million acres as of this week, according to the National Interagency Fire Center, the largest number of fires year-to-date the agency has recorded in the past decade. But many of these recent fires haven’t been igniting in California or the Pacific Northwest – which have endured several devastating fire seasons in a row – they’ve been popping up in places like Colorado and Texas, and have burned hundreds of thousands of acres in the past few weeks alone. Earlier in March, scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted drought conditions would expand eastward this spring and worsen in some locations – conditions that are now priming the landscape in the Southern Plains for dangerous, fast-moving fires…Climate researchers have said two major factors have contributed to the West’s multiyear drought: the lack of precipitation and an increase in evaporative demand, also known as the “thirst of the atmosphere.” Warmer temperatures increase the amount of water the atmosphere can absorb, which then dries out the landscape. That’s also true for places like Colorado and interior Texas, away from the Gulf Coast, Swain said. When the atmosphere extracts moisture from the soil without returning that water in the form of precipitation, there’s going to be less water available to those plants”.

Figure 3. A sampling of front page print coverage of climate change or global warming in the month of March.

Several political and economic themed media stories about climate change or global warming continued in March. To begin, in the legal arena a group called ‘ClientEarth’ sued Shell for ‘failing to properly prepare for the net zero transition’ and this drew media attention. For example, CNN journalist Angela Dewan reported, “Environmental lawyers ClientEarth said they were preparing legal action against the directors of Shell over the company's climate transition plan, in what they said would be the first such case of its kind. The lawyers from ClientEarth — which is a Shell shareholder — said they are seeking to hold the oil and gas company's 13 directors personally liable for what they consider to be a failure to adequately prepare for the global shift to a low-carbon economy. They say that the board has failed to adopt and implement a climate strategy that aligns with the 2015 Paris Agreement, claiming that amounts to an alleged breach of the directors' duties under the UK Companies Act. ClientEarth said it had written to Shell notifying it of its claim and was waiting for it to respond before filing papers at the High Court of England and Wales. For the case to proceed, ClientEarth would then need permission from the court to do so”.

Also in March, a report from the International Energy Agency about how to build resilience against shocks to fossil fuel supplies as well as impacts on climate change made news headlines. For example, CNN journalist Matt Egan reported, “Governments around the world must consider drastic steps to slash oil demand in the face of an emerging global energy crisis caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the International Energy Agency warned on Friday. The energy watchdog detailed a 10-point emergency plan that includes reducing speed limits on highways by at least 6 miles per hour, working from home up to three days a week where possible and car-free Sundays in cities. The recommendations for advanced economies like the United States and European Union would aim to offset the feared loss of nearly one-third of Russia’s oil production due to sanctions leveled on Moscow. Other steps in the emergency plan include increasing car sharing, using high-speed and night trains instead of planes, avoiding business air travel when possible and incentivizing walking, cycling and public transportation. An oil pumpjack pulls oil from the Permian Basin oil field on March 14, 2022 in Odessa, Texas. If fully implemented, the moves would lower world oil demand by 2.7 million barrels per day within four months – equal to the oil consumed by all the cars in China, the IEA said. And the impact would be greater if emerging economies like India and China adopted them in part or in full. However, the emergency steps would disrupt or even slow down a world economy that remains largely addicted to fossil fuels, especially for transportation. The IEA is suggesting the headaches would be better than the alternative”. Furthermore, New York Times journalists Catrin Einhorn and Lisa Friedman wrote, “The International Energy Agency said countries should encourage use of mass transit and car pooling, among other things. That could also help the climate crisis…Clean energy is the ultimate solution to tackling global warming and reducing energy dependency on other countries, many experts say. But it can’t come online fast enough to meet immediate demand. To make matters worse, countries were already far behind on the emissions reductions needed to meet the Paris Agreement, a global pledge intended to avoid the worst effects of climate change. While Western nations try to deal with the humanitarian crisis and the energy problems resulting from the war in Ukraine, “we should not forget a third crisis, which is the climate crisis,” Dr. Birol of the International Energy Agency said. “And as a result, all of the 10 measures we put on the table not only address the crude oil market tightness, but also help to pave the way to reach our climate goals””.

Further into March, in the US the Securities and Exchange Commission’s proposed regulation to require corporations to disclose their exposure to climate change risks was found to be newsworthy across several media outlets. For instance, Washington Post reporters Maxine Joselow and Douglass MacMillan wrote, “The Securities and Exchange Commission on Monday approved a landmark proposal to require all publicly traded companies to disclose their greenhouse gas emissions and the risks they face from climate change. The proposed rule from the Wall Street regulator mandates that hundreds of businesses report their planet-warming emissions in a standardized way for the first time. It reflects the Biden administration’s broader push to confront the dangers that climate change poses to the financial system and the nation’s economic stability. At an open meeting, the SEC’s three Democratic commissioners voted to approve the proposal, while the sole Republican commissioner voted against it. SEC Chair Gary Gensler, who was nominated by President Biden, said the rule would provide “consistent, comparable information” to investors. Environmentalists hailed the rule as a crucial first step in forcing the private sector to confront the economic risks of a warming world, even as some said the SEC should have gone further in requiring all businesses to disclose the emissions generated by their supply chain and customers. Some conservatives and business groups have opposed the federal government mandating any climate disclosures, and observers expect them to challenge the SEC proposal in court”.

Also in March, an announcement of a US and EU joint task force to reduce Europe’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels garnered media attention. For example, Associated Press correspondent Raf Casert reported, “With stunning speed, Russia’s war in Ukraine is driving Western Europe into the outstretched arms of the United States again, especially apparent when President Joe Biden offered a major expansion of natural gas shipments to his European Union counterpart Friday. Talking to European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, Biden said the core issue was “helping Europe reduce its dependency on Russian gas as quickly as possible.” And Europe, which relies on Moscow for 40% of the natural gas used to heat homes, generate electricity and drive industry, needs the help. An economic miscalculation with massive geopolitical consequences, many European Union nations let themselves become ever more reliant on Russian fossil fuels over the years, vainly hoping trade would overcome Cold War enmity on a continent too often riven by conflict. That longstanding practice meant the 27-nation bloc could not simply stop Russian energy imports as part of Western sanctions to punish Moscow for the invasion a month ago. And changing energy policy is about as cumbersome as turning around a liquefied natural gas carrier on a rough sea. In reality, it will take years. This is where Biden stepped in Friday. Under the plan, the United States and a few like-minded partners will increase exports of liquefied natural gas, or LNG, to Europe by 15 billion cubic meters this year. Those exports would triple in the years afterward, a necessary move if the EU can back up its claim to be rid of Russian imports in five years…Although the U.S.-EU initiative will likely require new facilities for importing liquefied natural gas, the White House said it is also geared toward reducing reliance on fossil fuels in the long run through energy efficiency and alternative sources of energy. But climate campaigners criticized the agreement and called instead for the U.S. and EU to focus on renewable energy and reducing fossil fuel demand”.

Furthermore, journalist Victor Martínez wrote in El Mundo, “Russia has historically been the great energy supplier of Europe through its coal, oil and gas. Until now, a reliable and vital partner for a continent weighed down by its enormous dependence on foreign energy. But these links have now become Europe's great weakness in its campaign of economic punishment of the Government of Vladimir Putin for the invasion of Ukraine”. The newspaper El País dedicated the editorial "Energy crisis and Europe" to him: “Russia's attack on Ukraine exposes the fragilities of the Union and will affect its plans against climate change. The energy price crisis, generated by the war, adds to the energy transition process undertaken by the European Union, which has led to the establishment of decarbonization objectives of 55% by 2030 and to achieve carbon neutrality in 2050. The delay in starting this transition is now being paid in two bills: that of the climate crisis, which is having worse effects than expected, as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has just pointed out, and that derived from Russian dependency.” In this way, the ecological transition is slowed down.

March media accounts also featured cultural stories relating to climate change or global warming. For example, stories of highways, Amazon deforestation and climate change were part of the media landscape. To illustrate, Washington Post journalist Terrence McCoy reported, “Stretches of the highway have been improved in recent years, making travel easier and unleashing a surge of deforestation. Many in the rainforest want the government to complete the job. President Jair Bolsonaro, who has worked to ease and undermine environmental regulations to promote development, says paving the highway would fulfill “a wish of the Amazonian people.” His vice president, a general in reserve, said he’d eat his own military beret if current officials don’t get it done. For many in Manaus, a city of 2.2 million cut off from Brazil’s main highway system, the road symbolizes something close to freedom — a lifeline that connects them to the rest of the country and paves the path toward development… In a region of both vast resources and pervasive poverty, many say the time has come to use what’s there for the taking, to seize the better life long denied by isolation and geography, to push back against federal laws and environmentalists who seem to care far more for trees than people. The outcome of the emotional political clash, scientists say, has implications not only for the rest of the forest but the world. The Amazon is a crucial bulwark against global warming, helping to slow the inexorable march of climate change. But researchers warn that finishing the highway and subsequent state roads would open up its core to destruction”.

Last, March media accounts about climate change or global warming with ecological and meteorological themes proliferated. For instance, Associated Press journalists Sam Metz and Felicia Fonseca reported, “A massive reservoir known as a boating mecca dipped below a critical threshold on Tuesday raising new concerns about a source of power that millions of people in the U.S. West rely on for electricity. Lake Powell’s fall to below 3,525 feet (1,075 meters) puts it at its lowest level since the lake filled after the federal government dammed the Colorado River at Glen Canyon more than a half century ago — a record marking yet another sobering realization of the impacts of climate change and megadrought. It comes as hotter temperatures and less precipitation leave a smaller amount flowing through the over-tapped Colorado River. Though water scarcity is hardly new in the region, hydropower concerns at Glen Canyon Dam in Arizona reflect that a future western states assumed was years away is approaching — and fast”.

Also in March, heat waves in various parts of the world such as the Arctic prompted several news accounts making links to a changing climate. For example, Guardian journalist Fiona Harvey wrote, “Startling heatwaves at both of Earth’s poles are causing alarm among climate scientists, who have warned the “unprecedented” events could signal faster and abrupt climate breakdown. Temperatures in Antarctica reached record levels at the weekend, an astonishing 40C above normal in places. At the same time, weather stations near the north pole also showed signs of melting, with some temperatures 30C above normal, hitting levels normally attained far later in the year. At this time of year, the Antarctic should be rapidly cooling after its summer, and the Arctic only slowly emerging from its winter, as days lengthen. For both poles to show such heating at once is unprecedented. The rapid rise in temperatures at the poles is a warning of disruption in Earth’s climate systems. Last year, in the first chapter of a comprehensive review of climate science, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned of unprecedented warming signals already occurring, resulting in some changes – such as polar melt – that could rapidly become irreversible. The danger is twofold: heatwaves at the poles are a strong signal of the damage humanity is wreaking on the climate; and the melting could also trigger further cascading changes that will accelerate climate breakdown. As polar sea ice melts, particularly in the Arctic, it reveals dark sea that absorbs more heat than reflective ice, warming the planet further. Much of the Antarctic ice covers land, and its melting raises sea levels”.

Also in March, the collapse of the Glenzer Conger ice shelf holding back two glaciers sparked many media stories. For example, Guardian journalist Donna Lu reported, “An ice shelf about the size of Rome has completely collapsed in East Antarctica within days of record high temperatures, according to satellite data. The Conger ice shelf, which had an approximate surface area of 1,200 sq km, collapsed around 15 March, scientists said on Friday. East Antarctica saw unusually high temperatures last week, with Concordia station hitting a record temperature of -11.8C on 18 March, more than 40C warmer than seasonal norms. The record temperatures were the result of an atmospheric river that trapped heat over the continent…Prof Matt King, who leads the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science, said because ice shelves are already floating, the Conger ice shelf’s break-up would not in itself impact sea level much. He said that fortunately the glacier behind the Conger ice shelf was small, so it would have a “tiny impact on sea level in the future”. “We will see more ice shelves break up in the future with climate warming,” King said. “We will see massive ice shelves – way bigger than this one – break up. And those will hold back a lot of ice – enough to seriously drive up global sea levels””.

Thanks for your ongoing interest in our Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) work monitoring media coverage of these intersecting dimensions and themes associated with climate change and global warming.

- report prepared by Max Boykoff, Rogelio Fernández-Reyes, Jennifer Katzung, Ami Nacu-Schmidt and Olivia Pearman