Monthly Summaries

Issue 83, November 2023

[DOI]

A resident of Rocinha carrying water collected from a natural spring during a heat wave in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on November 17, 2023. Photo: Tercio Teixera/AFP/Getty Images.

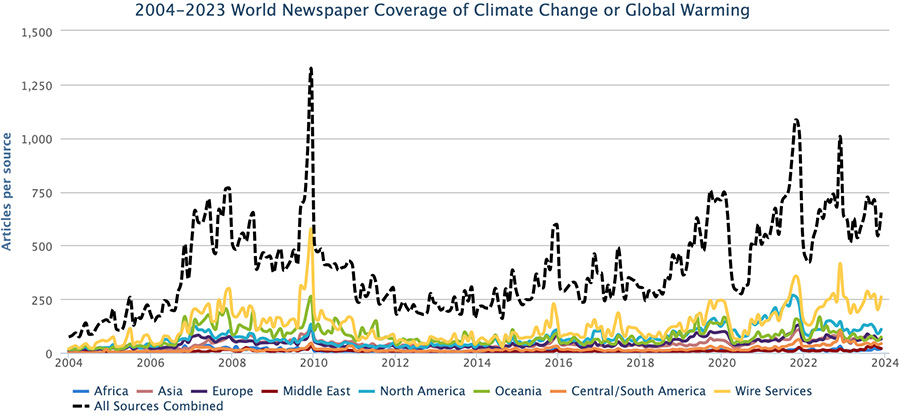

November media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe increased 21% from October 2023. However, coverage in November 2023 dropped 41% from November 2022 levels. This is largely attributed to attention paid in November 2022 to the United Nations (UN) climate negotiations (COP27) in Sharm el-Sheikh Egypt, while the UN climate negotiations in 2023 just began November 30 (COP28) in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. In November 2023, international wire services increased 30% from the previous month, while radio coverage went up 13% from October 2023. Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through November 2023.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through November 2023.

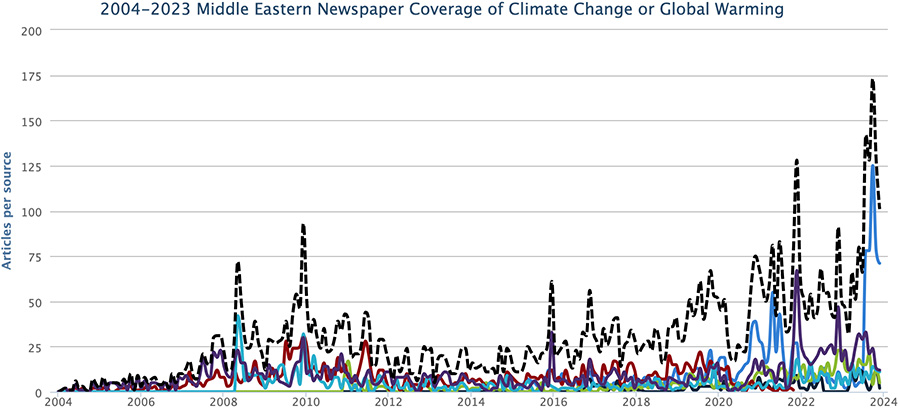

Compared with the preceding month, coverage increased in Asia (+7%), the European Union (EU) (+8%), Africa (+21%), North America (+23%), and Oceania (+28%). Meanwhile, November coverage decreased in Latin America (-3%), and in the Middle East (-21%) (see Figure 2) on the precipice of the opening of COP28 in Dubai.

Figure 2. Newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming in Middle East outletsfrom January 2004 through November 2023.

Our 26-member team at the Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) continues to provide three international and seven ongoing regional assessments of trends in coverage, along with 16 country-level appraisals each month. Visit our website for open-source datasets and downloadable visuals.

Moving to themes within analysis of content during the month, many political and economic-themed media stories about climate change or global warming populated the ‘news hole’ in October. To illustrate, in early November the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) released its annual Adaptation Gap report. The main finding – that financial support is lacking to help those in need to adapt to human-caused climate change – generated many headlines and news stories. For example, Washington Post journalist Maxine Joselow reported, “As climate change makes extreme weather events more intense and frequent, the world must spend hundreds of billions more a year — 10 to 18 times more than it currently spends — helping vulnerable people adapt to mounting devastation, United Nations experts said Thursday. The warning comes as millions of people suffer amid severe droughts, catastrophic wildfires and ruinous floods fueled by rising global temperatures. It also comes less than a month before the next U.N. Climate Change Conference, hosted this year in Dubai, where negotiators from wealthy countries are expected to resist calls to compensate poor nations for such deadly disasters”.

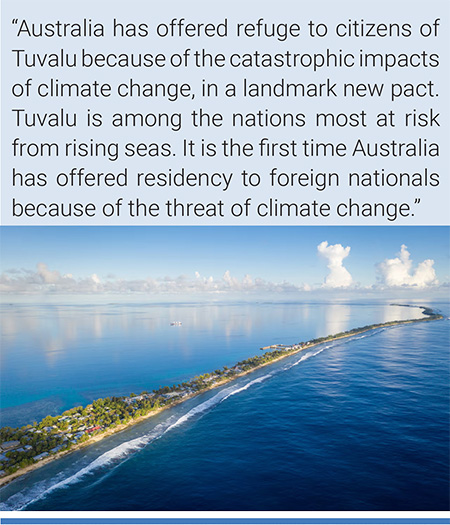

Aerial shot of the Funafuti atoll on Tuvalu showing the impact of rising sea levels. Photo: Sean Gallagher. |

Also in early November, another report from UNEP outlined how coal, oil and gas extraction plans flew in the face of work to alleviate the negative impacts of a changing climate. This made news. For example, Associated Press correspondent Jennifer McDermott reported, “Despite frequent and devastating heat waves, droughts, floods and fire, major fossil fuel-producing countries still plan to extract more than double the amount of fossil fuels in 2030 than is consistent with the Paris climate accord’s goal for limiting global temperature rise, according to a United Nations-backed study released Wednesday. Coal production needs to ramp sharply down to address climate change, but government plans and projections would lead to increases in global production until 2030, and in global oil and gas production until at least 2050, the Production Gap Report states. This conflicts with government commitments under the climate accord, which seeks to keep global temperature rise below 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit). The report examines the disparity between climate goals and fossil fuel extraction plans, a gap that has remained largely unchanged since it was first quantified in 2019. “Governments’ plans to expand fossil fuel production are undermining the energy transition needed to achieve net-zero emissions, creating economic risks and throwing humanity’s future into question,” Inger Andersen, executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme, said in a statement. As world leaders convene for another round of United Nations climate talks at the end of the month in Dubai, seeking to curb greenhouse gases, Andersen said nations must “unite behind a managed and equitable phase-out of coal, oil and gas — to ease the turbulence ahead and benefit every person on this planet.” The report is produced by the Stockholm Environment Institute, Climate Analytics, E3G, International Institute for Sustainable Development, and UNEP. They say countries should aim for a near-total phase-out of coal production and use by 2040 and a combined reduction in oil and gas production and use by three-quarters by 2050 from 2020 levels, at a minimum. But instead, the analysis found that in aggregate, governments plan to produce about 110% more fossil fuels in 2030 than what’s needed to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), and 69% more than would be consistent with the less protective goal of 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit). These global discrepancies increase even more toward 2050”.

As November wore on, news was generated by the announcement from the Australian government that they would offer residency-as-refuge to Tuvaluans due to climate-related rising sea levels. For example, BBC correspondent Tiffanie Turnbull reported, “Australia has offered refuge to citizens of Tuvalu because of the catastrophic impacts of climate change, in a landmark new pact. Tuvalu - a series of low-lying atolls in the Pacific - is among the nations most at risk from rising seas. It is home to 11,200 people and has repeatedly called for greater action to combat climate change. Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese described it as a "ground-breaking" agreement. Tuvalu Prime Minister Kausea Natano called it "a beacon of hope" and "not just a milestone but a giant leap forward in our joint mission to ensure regional stability, sustainability and prosperity". Up to 280 people per year will be granted the new visas, which will allow them to live, work and study in Australia. It is the first time Australia has offered residency to foreign nationals because of the threat of climate change, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation reported”.

In the EU, an emergent agreement to regulate and reduce methane emissions – designed to prompt countries like the US, Singapore, China and Russia to examine methane emissions in their supply chains – earned media attention. For example, Wall Street Journal correspondent Fabiana Negrin Ochoa noted, “The European Union has taken a step toward curbing methane emissions, agreeing on new rules aimed at cutting the amounts of the potent greenhouse gas produced in the energy sector. The EU Council and Parliament reached a provisional deal early Wednesday on regulation to track and reduce emissions of methane, thought to be responsible for a third of current global warming, the council said in a statement. The rules would require oil, gas and coal companies to measure, report and verify methane emissions, the statement said. They would also need to have mitigation measures in place to avoid emissions. Implementation would be phased, with operators submitting reports quantifying emissions within specific time frames once the regulations take effect. The measures also take aim at finding and repairing sources of methane leaks and other unintentional emissions, and ensuring that plugged or inactive wells aren’t contributing to the problem. Authorities will carry out periodic checks to verify compliance, the statement said. Imports of fossil fuels into the EU also fall under the scope of the new regulations. Exporters would need to comply with monitoring, reporting and verification measures by Jan. 1, 2027, and maximum methane intensity values by 2030. The next step for the new rules: being endorsed and formally adopted by the council and parliament. Curbing methane emissions is a key part of a legislative package to implement the European Green Deal, aimed at reaching climate neutrality by 2050. A climate-neutral economy is one with net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions. According to the International Energy Agency, oil, gas and coal-mining operations release large amounts of the potent greenhouse gas, either by accident or design. It estimates that the energy sector is responsible for nearly 40% of total methane emissions attributable to human activity, second only to agriculture”.

Moving to scientific-relatedthemes in coverage, there were many examples that earned media attention in November. Among them, a study – with findings that sparked some discussion and disagreement among fellow relevant expert scientists – by former NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies Director James Hanson and colleagues got media attention. For example, New York Times journalist Delger Erdenesanaa wrote, “Global warming may be happening more quickly than previously thought, according to a new study by a group of researchers including former NASA scientist James Hansen, whose testimony before Congress 35 years ago helped raise broad awareness of climate change. The study warns that the planet could exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius, or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, of warming this decade, compared with the average temperature in preindustrial days, and that the world will warm by 2 degrees Celsius by 2050. When countries signed the landmark Paris Agreement in 2015 to collectively fight climate change, they agreed to try and limit global warming to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius and aim for 1.5 degrees. “The 1.5 degree limit is deader than a doornail,” said Dr. Hansen, now the director of the Climate Science, Awareness and Solutions Program at Columbia University, during a news conference on Thursday. The 2 degrees goal could still be met, he said, but only with concerted action to stop using fossil fuels and at a pace far quicker than current plans. The world has warmed by about 1.2 degrees Celsius so far and is already experiencing worsening heat waves, wildfires, storms, biodiversity loss and other consequences of climate change. Past the Paris Agreement temperature goals, which reflect the results of international diplomacy rather than exact scientific benchmarks, the effects will get significantly worse and veer into territory with greater extremes and unknowns. Experts generally don’t quibble over the finding that the planet will soon pass 1.5 degrees of warming. A separate study published on Monday by British and Austrian scientists similarly found that, at our current rate of burning fossil fuels, the world would be committed to passing 1.5 degrees of warming within six years…So far, humans have increased the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by about 50 percent, from 280 parts per million in the 1700s to 417 parts per million in 2022 — resulting in a relatively linear temperature increase over time. But Dr. Hansen believes warming is accelerating. One reason, he said, is a successful reduction in sulfate aerosols in the atmosphere as countries and industries, especially shipping, have cracked down on air pollution in recent years. Different pollutants have different effects in the atmosphere. Sulfate aerosols, another byproduct of burning fossil fuels, reflect sunlight away from the surface of the Earth and help cool the planet slightly. Other prominent climate scientists, including Michael Mann at the University of Pennsylvania, who published a rebuttal of the new study, disagree that climate change is accelerating. Despite these disagreements, the very real, physical deadlines of 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius are looming close enough on the horizon that, to a certain extent, exactly how sensitive the Earth’s climate is to future greenhouse gas emissions doesn’t matter. Most experts agree that while the 1.5 degree goal has already been missed, 2 degrees is still salvageable — but not without much more action than countries are currently taking”.

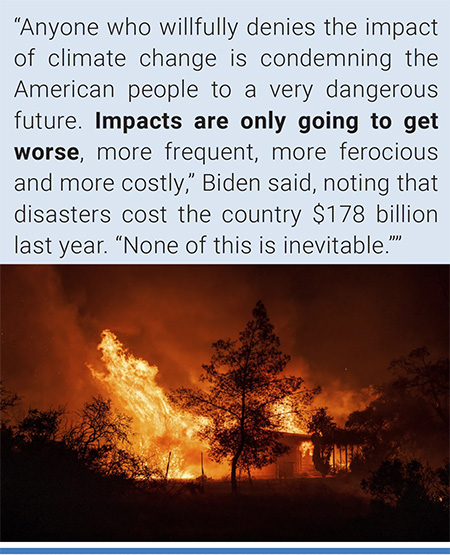

A structure is engulfed in flames as a wildfire called the Highland Fire burns in Aguanga, California on October 30. Photo: AP/Ethan Swope. |

Moving into mid-November, the 5th US National Climate Assessment Report release earned media attention from many outlets across the US, and some internationally. For example, Associated Press correspondents Seth Borenstein and Tammy Webber reported, “Revved-up climate change now permeates Americans’ daily lives with harm that is “already far-reaching and worsening across every region of the United States,” a massive new government report says. The National Climate Assessment, which comes out every four to five years, was released Tuesday with details that bring climate change’s impacts down to a local level. Unveiling the report at the White House, President Joe Biden blasted Republican legislators and his predecessor for disputing global warming. “Anyone who willfully denies the impact of climate change is condemning the American people to a very dangerous future. Impacts are only going to get worse, more frequent, more ferocious and more costly,” Biden said, noting that disasters cost the country $178 billion last year. “None of this is inevitable.” Overall, Tuesday’s assessment paints a picture of a country warming about 60% faster than the world as a whole, one that regularly gets smacked with costly weather disasters and faces even bigger problems in the future”.

Also in mid-November, findings from the latest annual Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change assessment – with two MeCCO team members (Lucy McAllister and Olivia Pearman) as co-authors – generated substantial media coverage. For example, CNN journalist Rachel Ramirez reported, “The climate crisis is carrying a mounting health toll that is set to put even more lives at risk without bold action to phase out planet-warming fossil fuels, a new report from more than 100 scientists and health practitioners found. The annual Lancet Countdown report, released Tuesday, found that delaying climate action will lead to a nearly five-fold increase in heat-related deaths by 2050, underscoring that the health of humans around the world is “at the mercy of fossil fuels.” Despite these growing health hazards and the costs of adapting to climate change soaring, authors say governments, banks and companies are still allowing the use of fossil fuels to expand and harm human health”.

Later in November, a new installment of the United Nations (UN) Emissions Gap report earned media coverage in many outlets. For example, Hindustan Times reporter Jayashree Nandi wrote, “97 nations covering approximately 81% of global greenhouse gas emissions had adopted net-zero pledges either in law (27 countries) or in a policy document (54 countries). All G20 members except Mexico have set net-zero targets, but overall net-zero goals do not inspire confidence, the report said. Net-zero is a target of completely negating the amount of greenhouse gases produced by human activity to be achieved by reducing emissions and implementing methods of absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Limited progress has been made on key indicators of confidence in net-zero implementation among G20 members, including legal status, existence and quality of implementation plans and alignment of near-term emissions trajectories, the report pointed out. None of the G20 nations, which include India, are currently reducing emissions at a pace consistent with meeting their net-zero targets, it added. The UNEP called on all nations to deliver economy-wide, low-carbon development. Coal, oil and gas extracted over the lifetime of producing and planned mines and fields would emit over 3.5 times the carbon budget available to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, and almost the entire budget available for 2 degrees of warming, the thresholds agreed upon by all countries in the Paris agreement. “The low-carbon development transition poses economic and institutional challenges for low and middle-income countries, but also provides significant opportunities. Transitions in such countries can help to provide universal access to energy, lift millions out of poverty and expand strategic industries,” the UNEP report said. “The associated energy growth can be met efficiently and equitably with low-carbon energy as renewables get cheaper, ensuring green jobs and cleaner air.” International financial assistance will have to be significantly scaled up, with new public and private sources of capital restructured through financing mechanisms for such a transition, the UNEP said”.

In late November, there was significant news attention paid to the European Copernicus Climate Change Service, who found that the Earth has warmed about 3.6oF (2oC) since the industrial revolution. As this corresponds with the UN Paris Agreement limit, it garnered concern in the public arena. For example, CNN correspondents Angela Dewan and Laura Paddison noted, “The Earth’s temperature briefly rose above a crucial threshold that scientists have been warning for decades could have catastrophic and irreversible impacts on the planet and its ecosystems, data shared by a prominent climate scientist shows. For the first time, the global average temperature on Friday last week was more than 2 degrees Celsius hotter than levels before industrialization, according to preliminary data shared on X by Samantha Burgess, deputy director of the Copernicus Climate Change Service, based in Europe. The threshold was crossed just temporarily and does not mean that the world is at a permanent state of warming above 2 degrees, but it is a symptom of a planet getting steadily hotter and hotter, and moving towards a longer-term situation where climate crisis impacts will be difficult — in some cases impossible — to reverse”.

Climate activists of Extinction Rebellion hold a protest action against private jets at the ExecuJet Aviation Group in Zaventem, near Brussels Airport. Photo: Nicolas Maeterlinck/Belga Mag/AFP via Getty Images. |

Also, several cultural-themed stories relating to climate change or global warming bubbled up during the month of November. Among them, an Oxfam report about wealth inequality relating to vastly different emissions contributions gained attention in the high-consuming regions of the EU and North America. For example, Washington Post journalist Kelly Kasulis Cho reported, “The world’s richest 1 percent generated as much carbon emissions as the poorest two-thirds in 2019, according to a new Oxfam report that examines the uber-wealthy’s lavish lifestyles and investments in heavily polluting industries. The report paints a grave portrait as climate experts and activists scramble to curtail global warming that is devastating vulnerable and often poor communities in Southeast Asia, East Africa and elsewhere. This month marked a long-dreaded milestone for the planet, when scientists recorded an average global temperature that was more than 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels on Friday. “The super-rich are plundering and polluting the planet to the point of destruction, leaving humanity choking on extreme heat, floods and drought,” Oxfam International’s interim executive director, Amitabh Behar, said in a news release on Monday. He called for world leaders to “end the era of extreme wealth.” According to Oxfam’s report, carbon emissions of the world’s richest 1 percent surpassed the amount generated by all car and road transport globally in 2019, while the richest 10 percent accounted for half of global carbon emissions that year. Meanwhile, emissions from the richest 1 percent are enough to cancel out the work of nearly 1 million wind turbines each year, Oxfam said. “None of this is surprising, but, you know, it’s crucial,” said David Schlosberg, director of the Sydney Environment Institute at the University of Sydney…According to the Oxfam report, which calls for a new wave of taxes on corporations and billionaires, “a 60 percent tax on the incomes of the richest 1 percent would cut emissions by more than the total emissions of the UK and raise $6.4 trillion a year to pay for the transition away from fossil fuels to renewable energy.” Some in recent years have also floated the idea of taxing high-carbon-emissions behavior, such as the purchase or use of private jets, yachts and high-end fossil fuel cars.”

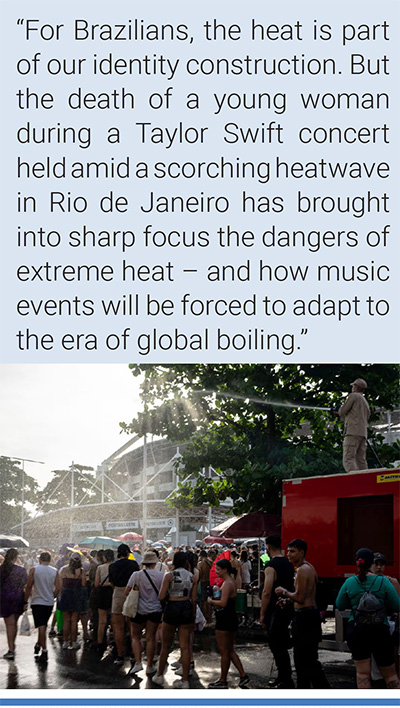

Meanwhile, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil the tragic heat-related death of a Taylor Swift enthusiast gave rise to several media stories making connections between the concert conditions and global warming. For example, US National Public Radio correspondent Alejandra Borunda reported, “Springtime is underway in the southern Hemisphere, but across much of South America it has felt like the depths of summer for months already. A string of heat waves have settled in over the region, pushing temperatures into record-breaking territory month after month. Last week, temperatures soared in southern Brazil. In Rio de Janeiro, a city of nearly 12 million people, intense heat and humidity pushed a 23-year-old Brazilian university student into cardiac arrest at a Taylor Swift concert. Fans had stood in line for the Eras Tour at the Nilton Santos Olympic stadium in brutally hot, humid, windless conditions for hours before the Friday night show. It was just as hot and steamy inside the venue, concertgoers reported. The woman who died, Ana Clara Benevides Machado, got medical attention from paramedics at the concert venue, but died later at a nearby hospital. Rio's temperatures last week topped 100 F. But the heat index–a measure that takes into account both air temperature and humidity–made it feel like it was nearly 140 degrees Fahrenheit. People can only handle heat like that for a few hours before they start to get sick–or even die. Brazil's Ministry of Culture noted the extreme, dangerous heat in a statement expressing condolences for Machado's death. This is a clear signal that climate change, the ministry said, has to be considered a major risk for events like big concerts or other cultural events now. Swift postponed a concert planned for Saturday night, another day that was supposed to be dangerously hot”. Meanwhile, Guardian journalist Constance Malleret noted, “In Brazil, a tropical country whose famed Carnival celebrations are held at the peak of summer, hot weather is not usually considered an obstacle to music events. “For Brazilians, the heat is part of our identity construction … We’re a country that deals well with heat, we’re proud of that,” said Nubia Armond, a geographer at Indiana University Bloomington. But the death of a young woman during a Taylor Swift concert held amid a scorching heatwave in Rio de Janeiro has brought into sharp focus the dangers of extreme heat – and how music events will be forced to adapt to the era of global boiling”.

Figure 3. Examples of newspaper front pages with climate change stories in November.

A firefighter cools off Taylor Swift concertgoers at the Nilton Santos Olympic Stadium. Photo: T. Teixeira/AFP. |

Finally, in November there were several ecological and meteorological dimensions of climate change or global warming. To illustrate, flooding in Eastern Africa – with links to a changing climate – generated media stories across the world. For example, BBC journalist Danai Nesta Kupemba reported, “At least 14 people have died because of flooding triggered by heavy rains in Somalia and thousands remain trapped. The flooding began last month as water levels in the Juba and Shabelle rivers began to rise, causing them to overflow. More than 47,000 people have fled their homes, the United Nations humanitarian affairs agency (OCHA) says. In Luuq district, 2,400 people are stuck in their own homes surrounded by water. Bridges and roads have been destroyed by the downpours, making it difficult to reach affected households. A number of toilets are overflowing into residential areas, raising the risks of water-borne diseases… El Niño is caused by the Pacific Ocean warming and is linked to flooding, cyclones, drought, and wildfires. Many factors contribute to flooding, but a warming atmosphere caused by climate change makes extreme rainfall more likely. The world has already warmed by about 1.10C since the industrial era began and temperatures will keep rising unless governments around the world make steep cuts to emissions”.

Also in November, Brazil suffered an unprecedented heat wave, and that generated news attention. For example, El País journalist Juan Royo Gual noted, “Heat waves in Brazil are becoming more frequent, as demonstrated by a study recently published by the Ministry of Science and Technology. The number of days a year with record temperatures has multiplied rapidly in 20 years. Between 1961 and 1990 it was something very exceptional, a maximum of seven days a year. Between 2011 and 2020, there was an average of 56 days of extreme heat (…) The first major heat wave of the season occurred with more than a month to go before the arrival of summer. An unprecedented wave in extension and duration. On the map of the National Institute of Meteorology (Inmet), two thirds of Brazil's territory appear painted orange and red, the colors for "danger" and "great danger." In this last category it is understood that there is a “high probability of damage and accidents, with risk to physical integrity or even human life,” according to the agency. A total of 1,413 municipalities in 13 states, among a total of about 5,000 municipalities, are in the risk zone, which is activated when temperatures reach five degrees above average for several consecutive days. Simultaneously, heavy rains are expected in the south.”

Thanks for your interest in our Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) work monitoring media coverage of these intersecting dimensions and themes associated with climate change and global warming.

- report prepared by Max Boykoff, Rogelio Fernández-Reyes, Jennifer Katzung, Ami Nacu-Schmidt and Olivia Pearman