Monthly Summaries

Issue 84, December 2023

[DOI]

United Nations Climate Chief Simon Stiell, right, and COP28 President Sultan al-Jaber embrace at the COP28 UN Climate Summit in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Photo: K. Jebreili/AP.

December media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe decreased 1% from November 2023. However, coverage in December 2023 went up 3% from December 2022 levels. Of particular note, in December 2023 international wire services dipped 18% from the previous month, while radio coverage went up 39% from December 2023.

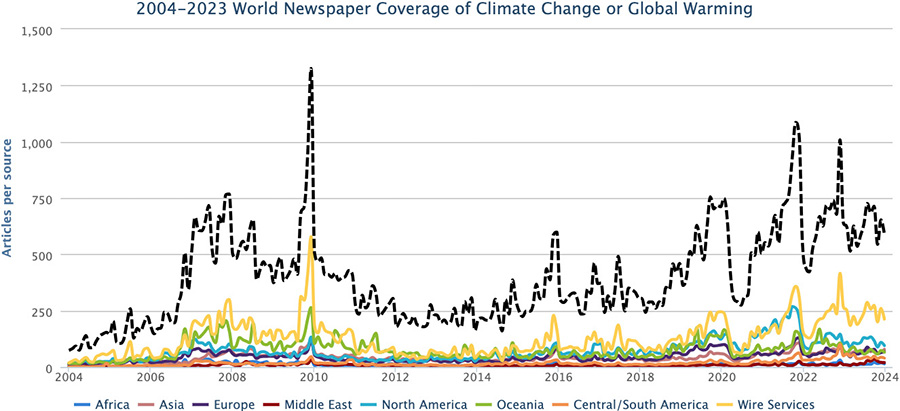

Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through December 2023. This composite now represents 20 years of our monitoring.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through December 2023.

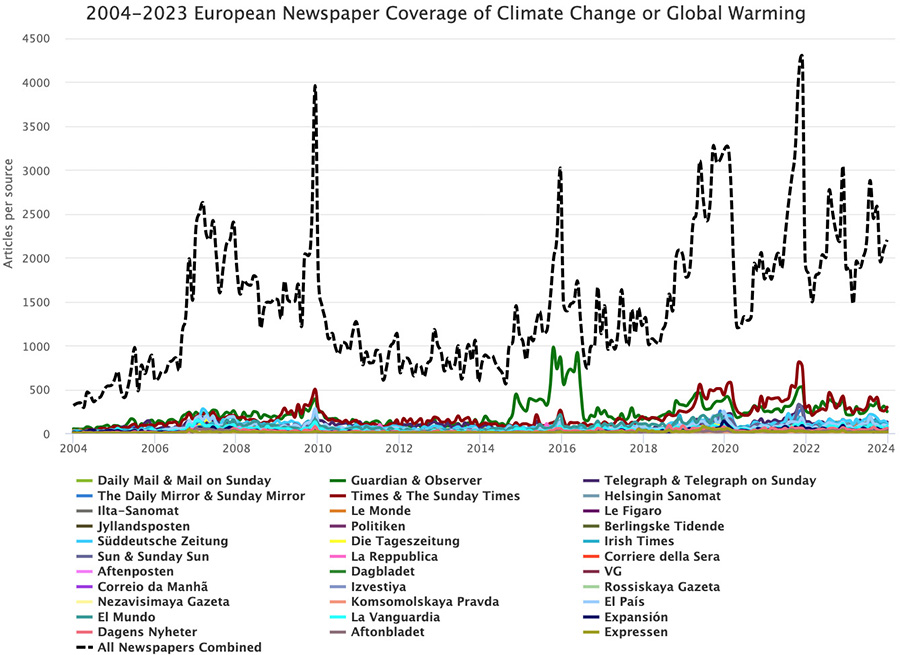

At the regional level, December 2023 coverage increased in Asia (+17%), the European Union (EU) (+5%) [see Figure 2] compared to the previous month of November. Yet, December coverage decreased in in the Middle East (-3%), Latin America (-8%), Oceania (-10%), North America (-13%), and Africa (-24%). These regional decreases appeared despite news surrounding the UN climate negotiations in 2023 (COP28) in Dubai, United Arab Emirates through December 12.

Figure 2. Newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming in European Union newspapers from January 2004 through December 2023.

Our dynamic team at the Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) continues to provide three international and seven ongoing regional assessments of trends in coverage, along with 16 country-level appraisals each month. Visit our website for open-source datasets and downloadable visuals.

Moving to the content of these stories, many political and economic-themed media stories about climate change or global warming dominated overall coverage this month. Most prominently, there were many news stories about the United Nations (UN) Conference of Parties (COP28) climate negotiations that were undertaken in the first two weeks of December in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. For example, New York Times correspondent Lisa Friedman reported, “A new fund to help vulnerable countries hit by climate disasters should be up and running this year, after diplomats from nearly 200 countries on Thursday approved a draft plan on the first day of a United Nations global warming summit. The early adoption of rules for the fund, which developing nations fought more than 30 years to create, was widely viewed as a positive sign for the two-week summit in Dubai. Sultan Al Jaber, the Emirati oil executive who is presiding over the conference, called the move a “significant milestone” and evidence that nations were ready to act with ambition on climate. The United Arab Emirates and Germany each pledged $100 million toward the fund and the United Kingdom pledged about $76 million. Japan pledged $10 million. The European Union would contribute at least €225 million (about $245 million), Wopke Hoekstra, the E.U. climate commissioner, said on X, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter. The United States promised $17.5 million, an amount that some activists criticized as too low for the world’s largest economy and biggest historic source of greenhouse gases”. Meanwhile, BBC correspondent Matt McGrath noted, “In a surprise that has lit up COP28, delegates have agreed to launch a long-awaited fund to pay for damage from climate-driven storms and drought.

Such deals are normally sealed last minute after days of negotiations. COP28 president Sultan al-Jaber shook up the meeting by bringing the decision to the floor on day one. The EU, UK, US and others immediately announced contributions totalling around $400m for poor countries reeling from the impacts of climate change. It's hoped the deal will provide the momentum for an ambitious wider agreement on action during the summit. The stakes for that couldn't be higher: the day began with stark warnings from the UN chief that "we are living through climate collapse in real time". António Guterres said the news that it's "virtually certain" 2023 will be the hottest year on record should "send shivers down the spines of world leaders"”.

Also, previous comments by COP28 president and ADNOC CEO Sultan Al Jaber made their way into the public sphere via news reporting in early December. While this comment was actually uttered in a public-facing Zoom conversation with past Irish President Mary Robinson in late November, this generated media attention in the first days of the UN climate negotiations (COP28). For example, Guardian journalists Damien Carrington and Ben Stockton wrote, “The president of COP28, Sultan Al Jaber, has claimed there is “no science” indicating that a phase-out of fossil fuels is needed to restrict global heating to 1.5C, the Guardian and the Centre for Climate Reporting can reveal. Al Jaber also said a phase-out of fossil fuels would not allow sustainable development “unless you want to take the world back into caves”. The comments were “incredibly concerning” and “verging on climate denial”, scientists said, and they were at odds with the position of the UN secretary general, António Guterres. Al Jaber made the comments in ill-tempered responses to questions from Mary Robinson, the chair of the Elders group and a former UN special envoy for climate change, during a live online event on 21 December. As well as running COP28 in Dubai, Al Jaber is also the chief executive of the United Arab Emirates’ state oil company, Adnoc, which many observers see as a serious conflict of interest. More than 100 countries already support a phase-out of fossil fuels and whether the final COP28 agreement calls for this or uses weaker language such as “phase-down” is one of the most fiercely fought issues at the summit and may be the key determinant of its success. Deep and rapid cuts are needed to bring fossil fuel emissions to zero and limit fast-worsening climate impacts. Al Jaber spoke with Robinson at a She Changes Climate event. Robinson said: “We’re in an absolute crisis that is hurting women and children more than anyone … and it’s because we have not yet committed to phasing out fossil fuel. That is the one decision that COP28 can take and in many ways, because you’re head of Adnoc, you could actually take it with more credibility.” Al Jaber said: “I accepted to come to this meeting to have a sober and mature conversation. I’m not in any way signing up to any discussion that is alarmist. There is no science out there, or no scenario out there, that says that the phase-out of fossil fuel is what’s going to achieve 1.5C.” Robinson challenged him further, saying: “I read that your company is investing in a lot more fossil fuel in the future.” Al Jaber responded: “You’re reading your own media, which is biased and wrong. I am telling you I am the man in charge.” Al Jaber then said: “Please help me, show me the roadmap for a phase-out of fossil fuel that will allow for sustainable socioeconomic development, unless you want to take the world back into caves.” “I don’t think [you] will be able to help solve the climate problem by pointing fingers or contributing to the polarisation and the divide that is already happening in the world. Show me the solutions. Stop the pointing of fingers. Stop it,” Al Jaber said. Guterres told COP28 delegates on Friday: “The science is clear: The 1.5C limit is only possible if we ultimately stop burning all fossil fuels. Not reduce, not abate. Phase out, with a clear timeframe.” Bill Hare, the chief executive of Climate Analytics, said: “This is an extraordinary, revealing, worrying and belligerent exchange. ‘Sending us back to caves’ is the oldest of fossil fuel industry tropes: it’s verging on climate denial.”

Activists protest against fossil fuels at the COP28 UN Climate Summit on December 5, in Dubai. Photo: Peter Dejong/AP. |

Among stories emerging from COP28, there was a great deal of attention paid to what was going into (and what was going to be left out of) the Dubai agreement among 198 parties to the UN. For example, Associated Press journalists Sibi Arasu and Seth Borenstein reported, “After days of shaving off the edges of key warming issues, climate negotiators Tuesday zeroed in on the tough job of dealing with the main cause of what’s overheating the planet: fossil fuels. As scientists, activists and United Nations officials repeatedly detailed how the world needs to phase-out the use of coal, oil and natural gas, the United Arab Emirates-hosted conference opened “energy transition day” with a session headlined by top officials of two oil companies. Negotiators produced a new draft of what’s expected to be the core document of the U.N. talks, something called the Global Stocktake, but it had so many possibilities in its 24-pages that it didn’t give too much of a hint of what will be agreed upon when the session ends next week. Whatever is adopted has to be agreed on by consensus so it has to be near unanimous. “It’s pretty comprehensive,” COP28 CEO Adnan Amin told The Associated Press Tuesday. “I think it provides a very good basis for moving forward. And what we’re particularly pleased about it is that it’s this early in the process””.

As COP28 wrapped in mid-December, many news accounts sought to help understand the various agreements that were made. For example, Associated Press journalists Seth Borenstein, David Keyton, Jamey Keaten and Sibi Arasu reported, “Nearly 200 countries agreed Wednesday to move away from planet-warming fossil fuels — the first time they’ve made that crucial pledge in decades of U.N. climate talks though many warned the deal still had significant shortcomings. The agreement was approved without the floor fight many feared and is stronger than a draft floated earlier in the week that angered several nations. But it didn’t call for an outright phasing out of oil, gas and coal, and it gives nations significant wiggle room in their “transition” away from those fuels. “Humanity has finally done what is long, long, long overdue,” Wopke Hoekstra, European Union commissioner for climate action, said as the COP28 summit wrapped up in Dubai. Within minutes of opening Wednesday’s session, COP28 President Sultan al-Jaber gaveled in approval of the central document — an evaluation of how off-track the world is on climate and how to get back on — without giving critics a chance to comment. He hailed it as a “historic package to accelerate climate action.” The document is the central part of the 2015 Paris accord and its internationally agreed-upon goal to try to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial times. The goal is mentioned 13 times in the document and al-Jaber repeatedly called that his “North Star.” So far, the world has warmed 1.2 degrees (2.2 degrees Fahrenheit) since the mid 1800s. Scientists say this year is all but certain to be the hottest on record. Several minutes after al-Jaber rammed the document through, Samoa’s lead delegate Anne Rasmussen, on behalf of small island nations, complained that they weren’t even in the room when al-Jaber said the deal was done. She said that “the course correction that is needed has not been secured,” with the deal representing business-as-usual instead of exponential emissions-cutting efforts. She said the deal could “potentially take us backward rather than forward.” When Rasmussen finished, delegates whooped, applauded and stood, as al-Jaber frowned, eventually joining the standing ovation that stretched longer than his plaudits. Marshall Islands delegates hugged and cried. Hours later, outside the plenary session, small island nations and European nations along with Colombia, held hands and hugged in an emotional show of support for greater ambition. But there was more self-congratulations Wednesday than flagellations. “I am in awe of the spirit of cooperation that has brought everybody together,” United States Special Envoy John Kerry said. He said it shows that nations can still work together despite what the globe sees with wars in Ukraine and the Middle East. “This document sends very strong messages to the world.” United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said in a statement that “for the first time, the outcome recognizes the need to transition away from fossil fuels.” “The era of fossil fuels must end — and it must end with justice and equity,” he said. United Nations Climate Secretary Simon Stiell told delegates that their efforts were “needed to signal a hard stop to humanity’s core climate problem: fossil fuels and that planet-burning pollution. Whilst we didn’t turn the page on the fossil fuel era in Dubai, this outcome is the beginning of the end.” Stiell cautioned people that what they adopted was a “climate action lifeline, not a finish line””.

Among critical media analyses, BBC reporter Dulcie Lee commented, “The host country, the United Arab Emirates, had built expectations sky-high in the first few days, with Jaber proposing a deal to "phase out" fossil fuels. In the end, the final pact doesn't go so far. It "calls on" countries to "transition away" from fossil fuels, and specifically for energy systems – but not for plastics, transport or agriculture. Moments later, the applause had turned to stunned silence when a delegate representing small island states, who are particularly vulnerable to climate change, accused the president of pushing through the text while they weren't in the room. The final text had a “litany of loopholes”, they said”.

Members of Our Children's Trust legal team at the first US youth climate change trial at Montana's First Judicial District Court. Photo: William Campbell/Getty Images. |

Several cultural-themed stories relating to climate change or global warming circulated during the month of December. Among them, there were stories about of the ongoing California lawsuit against the US Environmental Protection Agency on behalf of young people. For example, National Public Radio correspondent Jeff Brady reported, “Eighteen California children are suing the Environmental Protection Agency, claiming it violated their constitutional rights by failing to protect them from the effects of climate change. This is the latest in a series of climate-related cases filed on behalf of children. The federal lawsuit is called Genesis B. v. United States Environmental Protection Agency. According to the lawsuit, the lead plaintiff "Genesis B." is a 17-year-old Long Beach, California resident whose parents can't afford air conditioning. As the number of extreme heat days increases, the lawsuit says Genesis isn't able to stay cool in her home during the day. "On many days, Genesis must wait until the evening to do schoolwork when temperatures cool down enough for her to be able to focus," according to the lawsuit. The other plaintiffs range in age from eight to 17 and also are identified by their first names and last initials because they are minors. For each plaintiff, the lawsuit mentions ways that climate change is affecting their lives now, such as wildfires and flooding that have damaged landscapes near them and forced them to evacuate their homes or cancel activities”.

Also, media accounts in December covered stories with ecological and meteorological dimensions of climate change or global warming. Flooding in Australia – with links to a changing climate – provided an illustrative case. For example, BBC journalist Tiffanie Turnbull wrote, “Major floods have inundated parts of northern Queensland - with the heavy rain thwarting attempts to evacuate a settlement hit by rising water. Extreme weather driven by tropical cyclone Jasper has dumped a year's worth of rain on some areas…Eastern Australia has been hit by frequent flooding in recent years and the country is now enduring an El Nino weather event, which is typically associated with extreme events such as wildfires and cyclones. Australia has been plagued by a series of disasters in recent years - severe drought and bushfires, successive years of record floods, and six mass bleaching events on the Great Barrier Reef. A future of worsening disasters is likely unless urgent action is taken to halt climate change, the latest UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report warns”.

Elsewhere, several regions of Bolivia have declared an emergency due to lack of water. El País journalist Patricia R. Blanco wrote, “Bolivia is suffering an environmental catastrophe, seven of its nine departments have already declared an emergency due to drought and where fires have devastated almost three million hectares of the Bolivian Amazon (twice Mexico City), according to the Defensoría del Pueblo, and they have left large layers of pollution that have reached the country's large cities. Titicaca, the highest navigable lake in the world, is at its lowest level since records exist and in November 15 historical records for maximum temperatures were broken in different places in the country, according to the Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología. The prices of the basic basket, such as potatoes or goose (types of tuber), have tripled due to the drop in production caused by water scarcity. But in this country, the most vulnerable to climate change in South America and the one that can be most affected by the lack of water on the entire continent, according to the index of the American university of Notre Dame, the situation will worsen with the arrival of El Niño, expected for early 2024: this cyclical phenomenon will result in a total absence of rain in the Bolivian highlands. And if before El Niño arrives there continues to be no rainfall, El Alto and La Paz, the second and third most populated cities in the country, respectively, will run out of water in February, according to the Gestión Ambiental authorities of the two municipalities”.

Figure 3. Examples of newspaper front pages with climate change stories in December.

Many scientific themes continued to emerge in media stories during the month of December through new studies, reports, and assessments. To illustrate, a report from the Global Carbon Project noting a 1.1% increase in greenhouse gas emissions in 2023 (from 2022 levels) garnered attention. For example, Washington Post correspondent Shannon Osaka noted, “The last year has been filled with energy news that seems hopeful. The world has now installed more than 1 terawatt of solar panel capacity — enough to power the entire European Union. Purchases of electric vehicles have been surging: Over 1 million vehicles have been sold in the United States this year, with an estimated 14 million sold worldwide. And, looking at the rapid growth in wind, batteries and technologies such as heat pumps, you could be excused for thinking that the fight against climate change might actually be going … well. But a new analysis, released Tuesday morning local time as world leaders gather in Dubai to discuss the progress in cutting emissions, shows the grim truth: The surge in renewables has not been enough to displace fossil fuels. Global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels are expected to rise by 1.1 percent in 2023, according to the analysis from the Global Carbon Project. “Renewables are growing to record levels, but fossil fuels also keep growing to record highs,” said Glen Peters, a senior researcher at the Cicero Center for International Climate Research in Oslo who co-wrote the new analysis”.

Mangrove forests can protect land areas from rising sea levels and coastal abrasion, but they are at risk. Photo: Hotli Simanjuntak/EPA. |

Moreover, published research examining Earth’s support systems grabbed media headlines and stories in December. For example, Guardian correspondent Ajit Niranjan reported, “Many of the gravest threats to humanity are drawing closer, as carbon pollution heats the planet to ever more dangerous levels, scientists have warned. Five important natural thresholds already risk being crossed, according to the Global Tipping Points report, and three more may be reached in the 2030s if the world heats 1.5C (2.7F) above pre-industrial temperatures. Triggering these planetary shifts will not cause temperatures to spiral out of control in the coming centuries but will unleash dangerous and sweeping damage to people and nature that cannot be undone. “Tipping points in the Earth system pose threats of a magnitude never faced by humanity,” said Tim Lenton, from the University of Exeter’s Global Systems Institute. “They can trigger devastating domino effects, including the loss of whole ecosystems and capacity to grow staple crops, with societal impacts including mass displacement, political instability and financial collapse.” The tipping points at risk include the collapse of big ice sheets in Greenland and the West Antarctic, the widespread thawing of permafrost, the death of coral reefs in warm waters, and the collapse of one oceanic current in the North Atlantic. Unlike other changes to the climate such as hotter heatwaves and heavier rainfall, these systems do not slowly shift in line with greenhouse gas emissions but can instead flip from one state to an entirely different one. When a climatic system tips – sometimes with a sudden shock – it may permanently alter the way the planet works. Scientists warn that there are large uncertainties around when such systems will shift but the report found that three more may soon join the list. These include mangroves and seagrass meadows, which are expected to die off in some regions if the temperatures rise between 1.5C and 2C, and boreal forests, which may tip as early as 1.4C of heating or as late as 5C”.

Also in December, media stories ran in many outlets about the EU Copernicus Climate Change Service report that the past month was on pace to be the hottest December on record. For example, CBS News correspondent Li Cohen reported, “After months of expectation, it's official — 2023 will be the hottest year ever recorded. The European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service announced the milestone after analyzing data that showed the world saw its warmest-ever December. Last month was roughly 1.75 degrees Celsius warmer than the pre-industrial average, Copernicus said, with an average surface air temperature of 14.22 degrees Celsius, or about 57.6 degrees Fahrenheit. And now, Copernicus says that for January to December 2023, global average temperatures were the highest on record — 1.46 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial average”. As a second example, El País journalists Manuel Planelles, Clemente Álvarez and Laura Navarro noted, “From January to November, the planet's average temperature has been 1.46 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, and the annual variation is expected to be similar”.

Later in the month, the annual ‘Arctic Report Card’ published by researchers at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) earned media attention. For example, New York Times journalist Delger Erdenesanna wrote, “This summer was the Arctic’s warmest on record, as it was at lower latitudes. But above the Arctic Circle, temperatures are rising four times as fast as they are elsewhere. The past year overall was the sixth-warmest year the Arctic had experienced since reliable records began in 1900, according to the 18th annual assessment of the region, published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on Tuesday. “What happens in the Arctic does not stay in the Arctic,” said Rick Thoman, a climate specialist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and an editor of the new report, called the Arctic Report Card. The assessment defines the Arctic as all areas between 60 and 90 degrees north latitude. Greenland’s melting ice sheet is one of the biggest contributors to global sea level rise, and scientists are investigating links between weather in the Arctic and extreme weather farther south. The hottest spots on the Arctic map varied throughout the year. At the beginning of the year, temperatures over the Barents Sea north of Norway and Russia were as much as 5 degrees Celsius, or 9 degrees Fahrenheit, above the 1991-2020 average. In the spring, temperatures were also about 5 degrees Celsius hotter than average in northwest Canada. Hotter air temperatures dry out vegetation and soil, priming the pump for wildfires to burn more easily. This year, during Canada’s worst wildfire season on record, fires burned more than 10 million acres in the Northwest Territories. More than two-thirds of the territories’ population of 46,000 people had to be evacuated at various points and smoke from the fires reached millions more people, reducing air quality as far as the southern United States”.

Thanks for your interest in our Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) work monitoring media coverage of these intersecting dimensions and themes associated with climate change and global warming.

- report prepared by Max Boykoff, Rogelio Fernández-Reyes, Jennifer Katzung, Ami Nacu-Schmidt and Olivia Pearman