Monthly Summaries

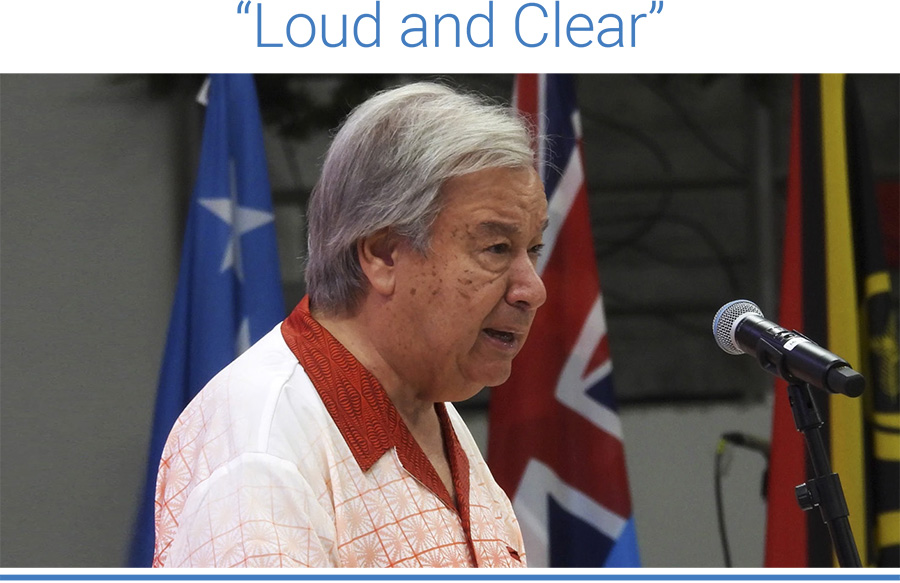

Issue 92, August 2024 | "Loud and Clear"

[DOI]

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres speaks at the opening of the annual Pacific Islands Forum leaders meeting in Nuku'alofa, Tonga on August 26, 2024. Photo: Charlotte Graham-McLay/AP.

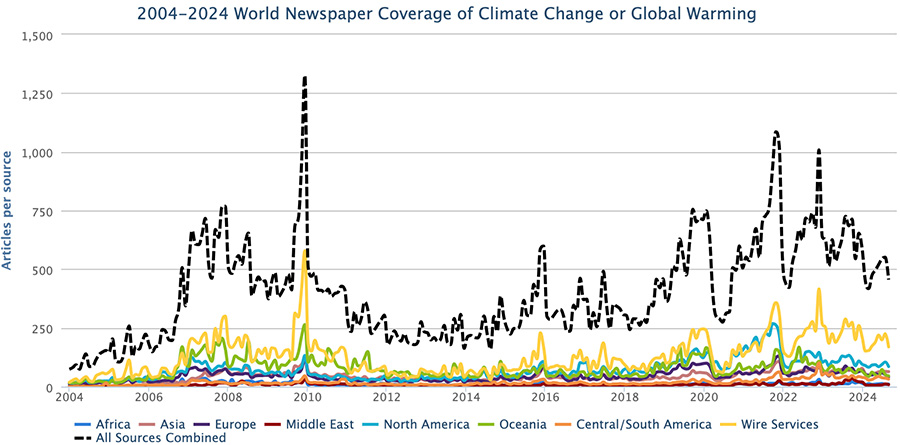

August media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe dropped 12% from July 2024. Meanwhile, coverage in August 2024 diminished 30% from August 2023 levels. Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through August 2024.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through August 2024.

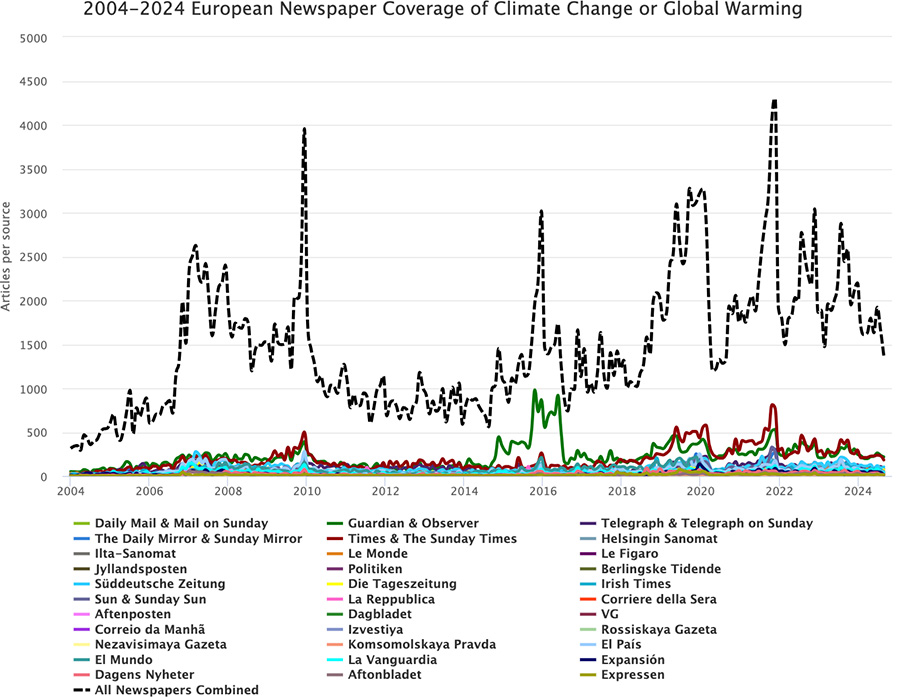

At the regional level, levels of August 2024 coverage went up in Africa (+15%) compared to the previous month of July. Meanwhile, coverage decreased in Asia (-1%), Oceania (-10%), Latin America (-11%), North America (-18%), the European Union (EU) (-18%) (Figure 2), and the Middle East (-25%).

Figure 2. European Union (EU) coverage of climate change or global warming from January 2000 through August 2024.

Our Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) team continues to provide three international and seven ongoing regional assessments of trends in coverage, along with 16 country-level appraisals each month. Visit our website for open-source datasets and downloadable visuals.

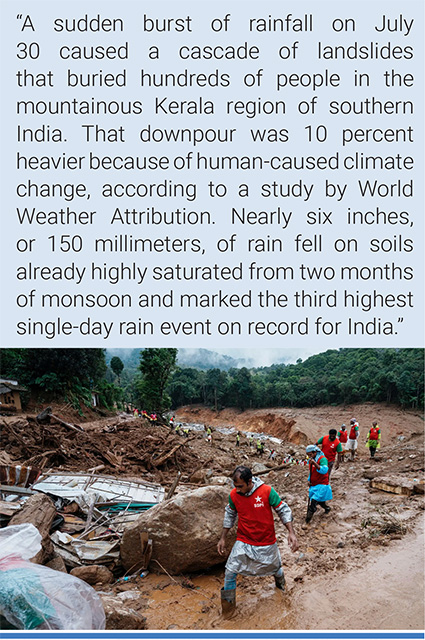

Rescuers searching through mud and debris after landslides in Wayanad district in Kerala, India, on August 1. Photo: Rafiq Maqbool/AP. |

Moving to the content of news coverage about climate change in August 2024, In August, there were many media stories relating to ecological and meteorological dimensions of climate change or global warming. To begin, as July gave way to August, heavy rainfall events in South Asia – with links to a changing climate – earned news attention. For example, New York Times journalist Austyn Gaffney reported, “A sudden burst of rainfall on July 30 caused a cascade of landslides that buried hundreds of people in the mountainous Kerala region of southern India. That downpour was 10 percent heavier because of human-caused climate change, according to a study by World Weather Attribution, a group of scientists who quantify how climate change can influence extreme weather. Nearly six inches, or 150 millimeters, of rain fell on soils already highly saturated from two months of monsoon and marked the third highest single-day rain event on record for India. “The devastation in northern Kerala is concerning not only because of the difficult humanitarian situation faced by thousands today, but also because this disaster occurred in a continually warming world,” said Maja Vahlberg, a climate risk consultant at the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre. “The increase in climate-change-driven rainfall found in this study is likely to increase the number of landslides that could be triggered in the future.” In a state that is highly prone to landslides, the Wayanad district is considered the riskiest part. As of Tuesday, at least 231 people had died and 100 remained missing”.

Elsewhere, heat waves in Northern Europe earned media coverage in August. In Finland, there were 63 heat days during the summer of 2024, which tied the record (a heat day is defined in Finland as a day when the temperature exceeds 25 degrees Celsius (77°F)). As an example of news coverage generated from heat in Europe, journalist Liisa Niemi from the Finnish Newspaper Helsingin Sanomat reported that, “Finland may have to get used to experiencing summer temperatures and even heat waves later into autumn. The end of this August has been warmer than usual. At the observation station in Salo [on the coast of Southern Finland], a temperature of 27 degrees (81°F) was measured on Friday afternoon." Despite the worried tone of the news story, it was headlined with a rather carefree tone: "Finnish summers are getting longer, says Finnish Meteorological Institute researcher”.

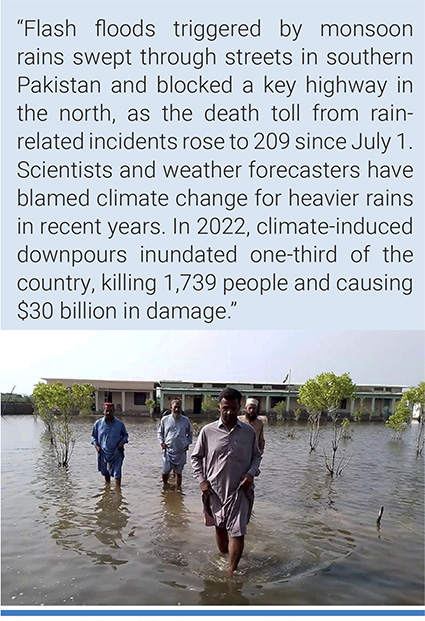

Villagers wade through flood areas caused by heavy monsoon rains near Sohbat Pur, an area of Pakistan's southwestern Baluchistan province. Photo: AP. |

Connecting issues of housing, flooding and wildfire risk, Washington Post journalist Sarah Kaplan reported, “As he looked at the Atlantic Ocean through the condo unit’s bedroom window, the sparkling blue water almost close enough to touch, Ed Morman knew this was where he wanted to spend the rest of his life. The 51-year-old was aware it might be risky moving to a barrier island on Florida’s Atlantic Coast, where relative sea levels have risen more than half a foot since 2010, according to a Washington Post analysis of tide gauge data. But the condo in Satellite Beach had everything else Morman and his wife were looking for: Warm weather. A welcoming community. A price they could afford in a place where they could one day retire. He turned to the real estate agent and said, “Yeah, we’re making an offer.” Morman and his wife moved from their Washington apartment to the Satellite Beach condo in February 2023. They are among more than 300,000 Americans who moved to flood- or fire-prone counties last year, despite the growing threat posed by climate change, according to a report from the real estate company Redfin. Drawing on data from the Census Bureau and the First Street Foundation, a nonprofit that assesses climate risk, the Redfin analysis showed that the counties most exposed to floods and fires gained more population than they lost between July 2022 and July 2023 — a continuation of a years-long trend of Americans disproportionately relocating to climate-vulnerable areas. But the report, provided exclusively to The Post, also revealed hints that migration patterns might be shifting. In fire-prone California, the highest-risk counties had a net outflow of nearly 7,000 people. And the net inflow to the nation’s high-flood-risk counties fell dramatically — a net population increase of just 16,144 last year after gaining 383,656 people between 2021 and 2022. Coming amid a summer of record heat, raging wildfires and a hurricane season that is projected to be among the worst in decades, the results suggest that climate change may be starting to hit home for Americans in a new way…”

In late August, flooding in Asia – with links to a changing climate – generated news coverage. For example, Associated Press journalist Munir Ahmed wrote, “Flash floods triggered by monsoon rains swept through streets in southern Pakistan and blocked a key highway in the north, officials said Monday, as the death toll from rain-related incidents rose to 209 since July 1. Fourteen people died across Punjab province in the past 24 hours, said Irfan Ali, an official at the provincial disaster management authority. Most of the other deaths have occurred in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh provinces. Pakistan’s annual monsoon season runs from July through September. Scientists and weather forecasters have blamed climate change for heavier rains in recent years. In 2022, climate-induced downpours inundated one-third of the country, killing 1,739 people and causing $30 billion in damage”.

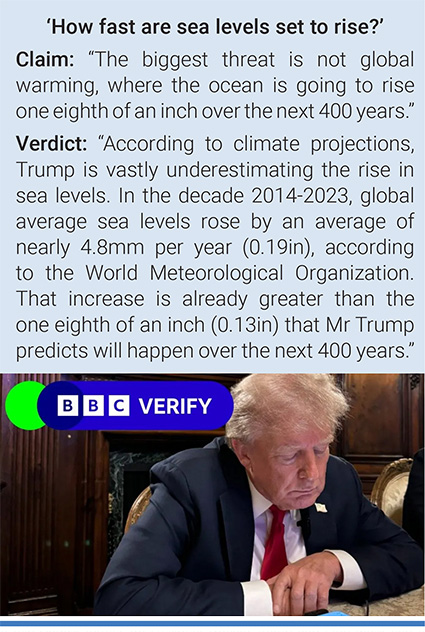

In mid-August former US President Donald Trump and Elon Musk had a two-hour live conversation on Twitter/X with ranging across topics including climate change. Photo: BBC News. |

Many political and economic-themed media stories about climate change or global warming also made news in August. For instance, in mid-August former US President Donald Trump and Elon Musk had a two-hour live conversation on Twitter/X with ranging across topics including climate change. This generated news attention. For example, BBC News reporters Jake Horton, Mark Poynting and Lucy Gilder noted, “In a two-hour discussion with Elon Musk, on the billionaire's platform X, Donald Trump made a number of questionable and false claims - which went largely unchallenged. The Republican presidential candidate returned to some familiar campaign themes, such as illegal immigration and rising prices, but he also talked about climate change. BBC Verify has been checking some of his claims. ‘How fast are sea levels set to rise?’ CLAIM: “The biggest threat is not global warming, where the ocean is going to rise one eighth of an inch over the next 400 years.” VERDICT: According to climate projections, Trump is vastly underestimating the rise in sea levels. In the decade 2014-2023, global average sea levels rose by an average of nearly 4.8mm per year (0.19in), according to the World Meteorological Organization. That increase is already greater than the one eighth of an inch (0.13in) that Mr Trump predicts will happen over the next 400 years. The magnitude of future rises is difficult to predict, because it is uncertain how quickly ice-sheets will melt, and future warming will depend on greenhouse gas emissions from human activities. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has estimated a likely range of 0.28 to 1.01m of global sea-level rise by 2100 - although higher rises can’t be ruled out. A sea-level rise of one metre would put hundreds of millions of people at risk of more regular coastal flooding, as well as submerging parts of low-lying countries such as the Maldives”.

At the US Democratic National Convention in August, Kamala Harris’ and Tim Walz’ climate policy track records as well as rhetoric about climate change at the convention earned media coverage. For example, CBS News correspondent Mary Cunningham reported, “The Democratic Party devoted seven pages of its 90-page 2024 platform to climate policy, offering a few clues about what Vice President Kamala Harris could do to combat climate change if she wins the presidency. Harris, who only emerged as her party's nominee in mid-July after President Biden dropped out of the race, has not yet articulated her own climate policy. The topic was scarcely mentioned at the Democratic convention this week, making the party platform the only guide to what climate policy in a Harris White House might be. During her nearly 40-minute long address at the Democratic National Convention on Thursday night, she talked about the economy, the war in Gaza, and immigration, but made just one brief reference to the issue in outlining the "fundamental freedoms" at stake in this election — "the freedom to breathe clean air, drink clean water, and live free from the pollution that fuels the climate crisis." Stevie O'Hanlon, a spokesperson for The Sunrise Movement, a youth-led climate group, said that Harris' decision not to speak more forcefully on climate change – both at the DNC and leading up to it – was a "missed opportunity"”.

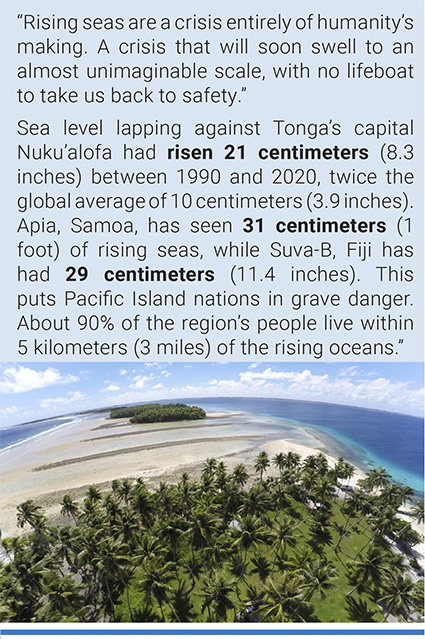

A section of land between trees is washed away due to rising seas in Majuro Atoll, Marshall Islands. Photo: Rob Griffith/AP. |

In the international political arena, United Nations (UN) Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ comments at a meeting of Pacific Island nations earned notable media attention. For example, Associated Press journalists Seth Borenstein and Charlotte Graham-Mclay noted, “Highlighting seas that are rising at an accelerating rate, especially in the far more vulnerable Pacific island nations, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres issued yet another climate SOS to the world. This time he said those initials stand for “save our seas.” The United Nations and the World Meteorological Organization Monday issued reports on worsening sea level rise, turbocharged by a warming Earth and melting ice sheets and glaciers. They highlight how the Southwestern Pacific is not only hurt by the rising oceans, but by other climate change effects of ocean acidification and marine heat waves. Guterres toured Samoa and Tonga and made his climate plea from Tonga’s capital on Tuesday at a meeting of the Pacific Islands Forum, whose member countries are among those most imperiled by climate change. Next month the United Nations General Assembly holds a special session to discuss rising seas. U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres issued yet another climate SOS to the world, highlighting seas that are rising at an accelerating rate, especially in the far more vulnerable Pacific island nations. “This is a crazy situation,” Guterres said. “Rising seas are a crisis entirely of humanity’s making. A crisis that will soon swell to an almost unimaginable scale, with no lifeboat to take us back to safety.” “A worldwide catastrophe is putting this Pacific paradise in peril,” he said. “The ocean is overflowing.” A report that Guterres’ office commissioned found that sea level lapping against Tonga’s capital Nuku’alofa had risen 21 centimeters (8.3 inches) between 1990 and 2020, twice the global average of 10 centimeters (3.9 inches). Apia, Samoa, has seen 31 centimeters (1 foot) of rising seas, while Suva-B, Fiji has had 29 centimeters (11.4 inches). “This puts Pacific Island nations in grave danger,” Guterres said. About 90% of the region’s people live within 5 kilometers (3 miles) of the rising oceans, he said. Since 1980, coastal flooding in Guam has jumped from twice a year to 22 times a year. It’s gone from five times a year to 43 times a year in the Cook Islands. In Pago Pago, American Samoa, coastal flooding went from zero to 102 times a year, according to the WMO State of the Climate in the South-West Pacific 2023 report… Guterres is amping up his rhetoric on what he calls “climate chaos” and urged richer nations to step up efforts to reduce carbon emissions, end fossil fuel use and help poorer nations. Yet countries’ energy plans show them producing double the amount of fossil fuels in 2030 than the amount that would limit warming to internationally agreed upon levels, a 2023 UN report found. Guterres said he expects Pacific island nations to “speak loud and clear” in the next General Assembly, and because they contribute so little to climate change, “they have a moral authority to ask those that are creating accelerating the sea level rise to reverse these trends””.

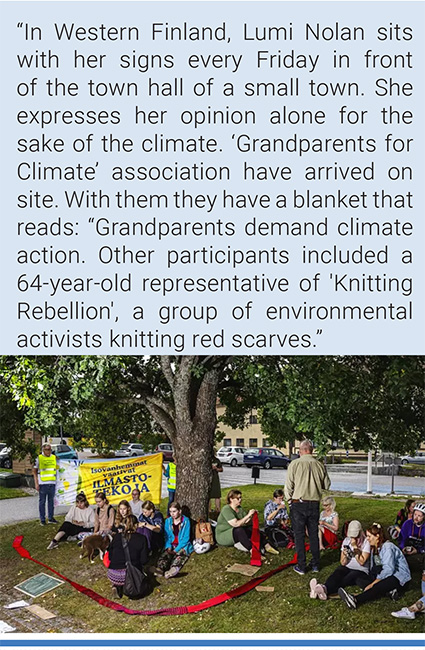

A couple of dozen people gathered at Tamme, Finland. Photo: Ville-Veikko Kaakinen / HS. |

Media portrayals in August 2024 also featured related and ongoing cultural-themed stories relating to climate change or global warming. To illustrate, challenges and opportunities of civic engagement were highlighted in August articles published by the Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat. First, journalist Inka Salmi reported about a young climate activist who persistently tries to appeal decision-makers, writing, “In Western Finland, a 13-year-old girl sits with her signs every Friday in front of the town hall of a small town. She expresses her opinion alone for the sake of the climate. Lumi Nolan hopes that one day others will join her.” Second, Helsingin Sanomat journalist Milja Virtanen noted, “‘Grandparents for Climate’ association have arrived on site. With them they have a blanket that reads: "Grandparents demand climate action." They've brought coffee, hot chocolate, cinnamon buns and toffee candies for the people.” Other participants included a 64-year-old representative of "Knitting Rebellion", a group of environmental activists knitting red scarves. She commented that “We adults are responsible for this, not the children. It fills me with sadness and a little frustration that adults don't support children more.” She further explains that: "The plan is to take the scarves to Brussels. There, they will be used to demand action from politicians, adhering to the Paris Climate Agreement”.

Elsewhere, climate social movement activities in South Korea garnered media interest. For example, Guardian journalist Raphael Rashid reported, “South Korea’s constitutional court has ruled that part of the country’s climate law does not conform with protecting the constitutional rights of future generations, an outcome local activists are calling a “landmark decision”. The unanimous verdict concludes four years of legal battles and sets a significant precedent for future climate-related legal actions in the region. The court found that the absence of legally binding targets for greenhouse gas reductions for the period from 2031-49 violated the constitutional rights of future generations and failed to uphold the government’s duty to protect those rights. The court said this lack of long-term targets shifted an excessive burden to the future. It gave the national assembly and government until 28 February 2026 to amend the law to include these longer-term targets. The decision echoes a similar ruling by Germany’s federal constitutional court in 2021, which found the country’s climate law lacked sufficient provisions for emission reductions beyond 2030, potentially infringing on the freedoms of future generations. South Korea’s climate litigation began in March 2020 when Youth 4 Climate Action, a group leading the Korean arm of the global school climate strike movement, filed the first lawsuit, alleging that the government’s inadequate greenhouse gas reduction targets violated citizens’ fundamental rights, particularly those of future generations. Subsequently, three additional lawsuits were consolidated, bringing the number of plaintiffs to 255. These plaintiffs represented a wide age range, including children, babies, and even a foetus at the time of filing, emphasising the long-term impact of climate policy on future generations. Activists including Kim Seo-gyeong from Youth 4 Climate Action said they saw the court’s decision not as the end but as the beginning of a renewed push for more ambitious climate action”.

Last, several August 2024 media stories featured several scientific themes in news accounts. In particular, new research in the journal Nature about rising ocean temperatures around Australia’s Great Barrier reef earned news coverage. For example, Associated Press journalist Suman Naishadham reported, “Ocean temperatures in the Great Barrier Reef hit their highest level in 400 years over the past decade, according to researchers who warned that the reef likely won’t survive if planetary warming isn’t stopped. During that time, between 2016 and 2024, the Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest coral reef ecosystem and one of the most biodiverse, suffered mass coral bleaching events. That’s when water temperatures get too hot and coral expel the algae that provide them with color and food, and sometimes die. Earlier this year, aerial surveys of over 300 reefs in the system off Australia’s northeast coast found bleaching in shallow water areas spanning two-thirds of the reef, according to Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. Researchers from Melbourne University and other universities in Australia, in a paper published Wednesday in the journal Nature, were able to compare recent ocean temperatures to historical ones by using coral skeleton samples from the Coral Sea to reconstruct sea surface temperature data from 1618 to 1995. They coupled that with sea surface temperature data from 1900 to 2024. They observed largely stable temperatures before 1900, and steady warming from January to March from 1960 to 2024. And during five years of coral bleaching in the past decade — during 2016, 2017, 2020, 2022 and 2024 — temperatures in January and March were significantly higher than anything dating back to 1618, researchers found. They used climate models to attribute the warming rate after 1900 to human-caused climate change. The only other year nearly as warm as the mass bleaching years of the past decade was 2004”.

Figure 3. Examples of newspaper front pages with climate change stories in August 2024.

Thanks for your interest in our Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) work monitoring media coverage of these intersecting dimensions and themes associated with climate change and global warming.

- report prepared by Max Boykoff, Rogelio Fernández-Reyes, Jari Lyytimäki, Erkki Mervaala, Ami Nacu-Schmidt, Jeremiah Osborne-Gowey and Olivia Pearman