Monthly Summaries

Issue 95, November 2024 | "Get ahead of the game"

[DOI]

This holiday season, contribute to MeCCO’s ongoing work via this link to make a donation. |

The construction project to build the Kayenta solar farms on the Navajo Nation, shown here in 2018, employed hundreds of people, nearly 90 percent of whom were Navajo citizens. Photo: Navajo Tribal Utility Authority / Navajo Nation.

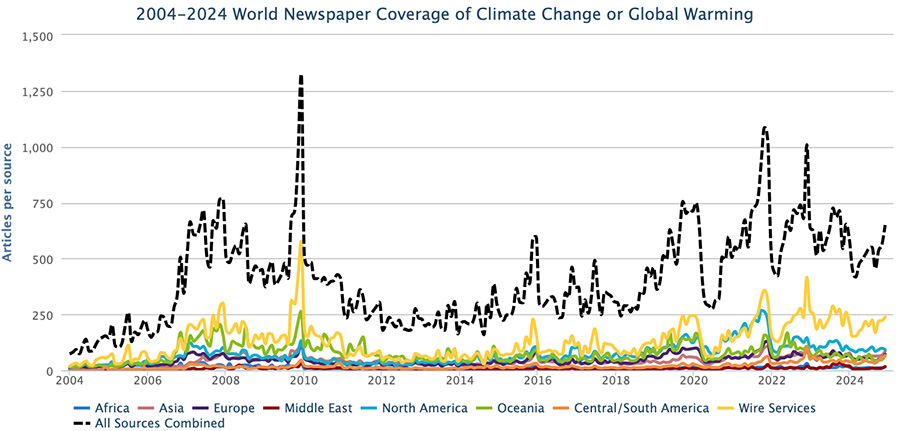

November media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe increased 24% from October 2024. Furthermore, coverage in November 2024 went up 10% from November 2023. Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through November 2024.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through November 2024.

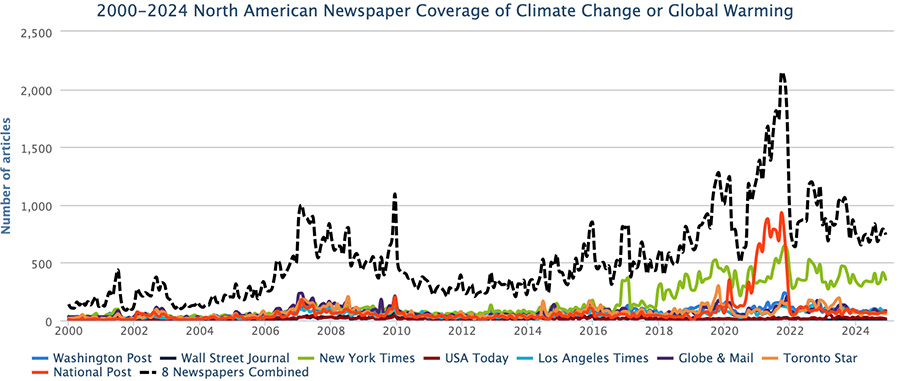

At the regional level, November 2024 coverage went up in all regions except in North America which dropped 6% (figure 2 shows this regional trend): Latin America rose 20%, Asia increased 26%, the European Union (EU) went up 40%, Oceania jumped 41%, Africa surged 47%, and the Middle East shot up 70% compared to the previous month of October.

Figure 2. Coverage of climate change or global warming in North America – Globe & Mail (Canada), Los Angeles Times (US), National Post (Canada), New York Times (US), Toronto Star (Canada), USA Today (US), Wall Street Journal (US), and Washington Post (US) – from January 2004 through November 2024.

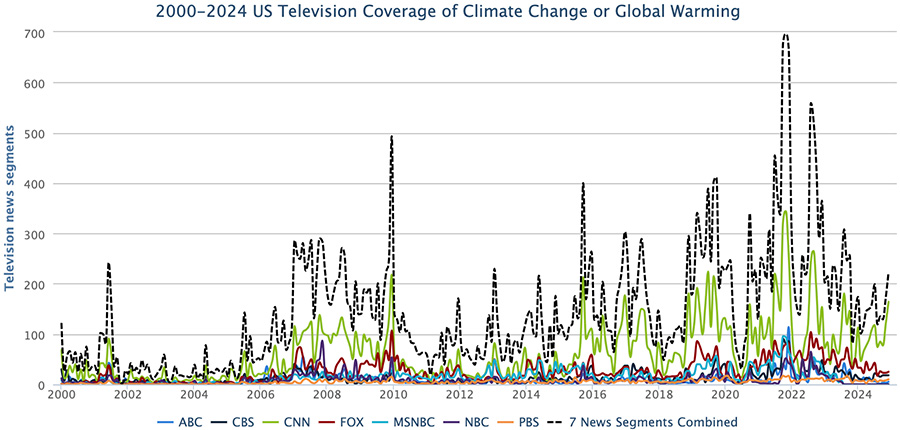

Among our country-level monitoring, for example United States (US) print coverage dropped 12% while US television coverage went up 29% (see Figure 3) in November 2024 compared to the previous month of October. The push of large global events like the United Nations (UN) climate negotiations (COP29) and the pull of domestic US elections contributed to these differing trends in a finite news hole particularly in daily print media sources.

Figure 3. US television – ABC, CBS, CNN, FOX, MSNBC, NBC, and PBS – coverage of climate change or global warming from January 2000 through November 2024.

To begin, political and economic-themed media stories about climate change or global warming dominated television, radio and newspaper outlets in November. For example, the outcome of the US Presidential election generated news coverage around the world that considered how the incoming second Trump Administration climate policy stances may influence progress at international and national levels. For example, Le Monde journalist Matthieu Goar reported, “At 73, Tom Vilsack is having a moment of political déjà vu. On Tuesday, November 19, the US Secretary of Agriculture spoke at the United Nations climate change summit, COP29, to defend the environmental record of outgoing president Joe Biden – a final stock take before once again handing over the reins to Donald Trump's administration. He was in the same post when Trump was first elected in 2016. With the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), he said, the Biden administration had "delivered the most ambitious climate change clean energy and conservation agenda in US history." As for the continuation of that agenda, he said: "It isn't going to be the administration that continues this, it's going to be the people who have received the benefit... who understand [that] it's in their best interest to preserve it and to continue it. The funding is available, it's already been committed." He listed some of the $369 billion (€348 billion) that the IRA has helped to start pumping into green industry, adding: "There's a ground swell, a momentum that I don't think an incoming administration, regardless of its attitudes about climate, would be in a position to stop." Words very similar to those of Biden. "Some may seek to deny or delay the clean energy revolution that's underway in America, but nobody – nobody – can reverse it," the outgoing president quipped on Sunday, November 17, during a trip to Manaus, in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon rainforest, on the sidelines of the G20 summit. The incoming president, a climate change skeptic, has monopolized conversations at COP29. When he returns to lead the country that has emitted the most greenhouse gases in history, Trump has promised to withdraw from the Paris Agreement – as he did in 2017”.

US secretary of agriculture Tom Vilsack and Council on Environmental Quality president Brenda Mallory at COP29. Photo: Murad Sezer/Reuters. |

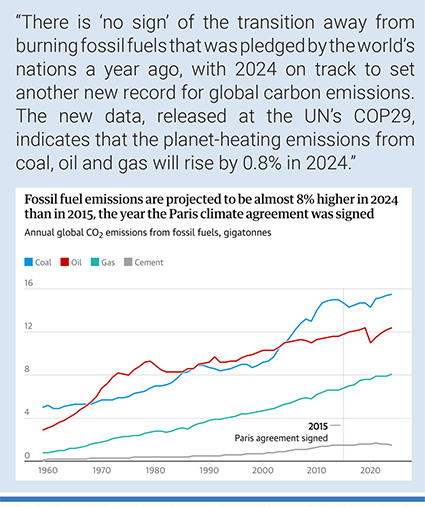

This kind of coverage then spilled into news attention paid to uncertainty about progress to be made during the two-week United Nations (UN) climate negotiations (COP29) in Baku, Azerbaijan. For example, Guardian environment editor Damien Carrington reported, “There is ‘no sign’ of the transition away from burning fossil fuels that was pledged by the world’s nations a year ago, with 2024 on track to set another new record for global carbon emissions. The new data, released at the UN’s COP29 climate conference in Azerbaijan, indicates that the planet-heating emissions from coal, oil and gas will rise by 0.8% in 2024. In stark contrast, emissions have to fall by 43% by 2030 for the world to have any chance of keeping to the 1.5C temperature target and limiting ‘increasingly dramatic’ climate impacts on people around the globe. The world’s nations agreed at COP28 in Dubai in 2023 to ‘transition away’ from fossil fuels, a decision hailed as a landmark given that none of the previous 27 summits had called for restrictions on the primary cause of global heating. On Monday, the COP28 president, Sultan Al Jaber, told the summit in Baku: “History will judge us by our actions, not by our words.” The rate of increase of carbon emissions has slowed over the last decade or so, as the rollout of renewable energy and electric vehicles has accelerated. But after a year when global heating has fueled deadly heatwaves, floods and storms, the pressure is on the negotiators meeting in Baku to finally reach the peak of fossil fuel burning and start a rapid decline. COP29 will focus on mobilizing the trillion dollars a year needed for developing nations to curb their emissions as they improve the lives of their citizens and to protect them against the now inevitable climate chaos to come. The summit also aims to increase the ambition of the next round of countries’ emission-cutting pledges, due in February. The new data comes from the Global Carbon Budget project, a collaboration of more than 100 experts led by Prof Pierre Friedlingstein, at the University of Exeter, UK. “The impacts of climate change are becoming increasingly dramatic, yet we still see no sign that burning of fossil fuels has peaked. Time is running out and world leaders meeting at COP29 must bring about rapid and deep cuts to fossil fuel emissions.” Prof Corinne Le Quéré, at the University of East Anglia, UK, said: “The transition away from fossil fuels is clearly not happening yet at the global level, but our report does highlight that there are 22 countries that have decreased their emissions significantly [while their economies grew].” The 22 countries, representing a quarter of global emissions, include the UK, Germany and the US”.

Guardian graphic. Source: Global Carbon Budget, Friedlingstein et al. Earth System Science Data, 2024. |

For example, BBC News correspondents Georgina Rannard and Maia Davies wrote, “The president of COP29’s host country has told the UN climate conference that oil and gas are a "gift of God". Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev criticized "Western fake news" about the country's emissions and said nations "should not be blamed" for having fossil fuel reserves. The country plans to expand gas production by up to a third over the next decade. Shortly afterwards, UN chief António Guterres told the conference that doubling down on the use of fossil fuels was "absurd". He said the "clean energy revolution" had arrived and that no government could stop it. Separately, UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer pledged further reductions on emissions, saying the UK will now aim for an 81% decrease by 2035. The UK called for other countries to match the new target. "Make no mistake, the race is on for the clean energy jobs of the future, the economy of tomorrow, and I don't want to be in the middle of the pack - I want to get ahead of the game," Sir Keir told the conference. Some observers had expressed concerns about the world’s largest climate conference taking place in Azerbaijan. Its minister for ecology and natural resources - a former oil executive that spent 26 years at Azerbaijan’s state-owned oil and gas company Socar – is the conference's chairman. There are also concerns that Azerbaijani officials are using COP29 to boost investment in the country’s national oil and gas company. But addressing the conference on its second day, President Aliyev said Azerbaijan had been subject to "slander and blackmail" ahead of COP29. He said it had been as if "Western fake news media", charities and politicians were "competing in spreading disinformation... about our country". Aliyev said the country’s share in global gas emissions was "only 0.1%". "Oil, gas, wind, sun, gold, silver, copper, all... are natural resources and countries should not be blamed for having them, and should not be blamed for bringing these resources to the market, because the market needs them." Oil and gas are a major cause of climate change because they release planet-warming”.

Many media accounts also examined various country positions and actions relating to COP29 as well as concurrent political dynamics. For example, El Observador journalist Andrés Fidanza reported, “Argentine Foreign Minister Gerardo Werthein assured in exclusive statements to El Observador's special envoy that Argentina will not abandon the Paris Agreement, although the government is in the process of reviewing its position regarding this treaty and other international commitments related to climate change. "We are simply re-evaluating our positions," Werthein said, adding that there are elements of the Paris Agreement with which Javier Milei's government does not agree. This approach was reaffirmed by Werthein days ago in an interview with The New York Times, where he said that Argentina is reviewing its participation in all climate agreements. However, so far, no decision has been made to withdraw. And Werthein stressed that Argentina is not abandoning it. "We are not leaving the Paris agreement," he told this newspaper. The Paris Agreement, adopted in 2015 by 196 countries, aims to keep the increase in global average temperature well below 2 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels by limiting carbon emissions. It is a legally binding treaty and considered a central pillar of the global fight against climate change. President Milei, who has repeatedly questioned the causes attributed to climate change, maintains that the phenomenon is real, but attributes it to natural historical cycles , ruling out that it is exclusively caused by human activity. This approach differentiates him from the predominant narrative in the scientific community and in international organizations”.

Delegates at the COP29 climate summit in Baku, Azerbaijan, on Wednesday. Photo: Maxim Shemetov/Reuters. |

Central to COP29 were deliberations, discussions, debates and decisions regarding climate finance. Media stories covered these dynamics each step of the way across the two weeks of negotiations in November. During the negotiations, for example Hindustan Times journalist Jayashree Nandi reported, “After developing countries rejected the first draft on the new collective quantified goal (NCQG), on Tuesday, co-chairs of the programme on NCQG at the COP 29 climate talks in Baku released another iteration on Wednesday morning that runs into 34 pages. The options span a wide range reflecting priorities and preferences of all negotiating groups among developed and developing countries -- from a floor of $100 billion to $ 2 trillion. It also has options for contributors , reflecting the evolved and dynamic nature of emissions and their economic capabilities. NCQG, a new finance target to replace the Paris Agreement’s $100 billion a year, is one of the desired outcomes of the Baku climate talks, although most experts believe that achieving this will be tough. The drafting process indicates this. The latest draft suggests that NCQG is meant to accelerate the achievement of Article 2 of the Paris Agreement (to try and keep global warming to 1.5 degrees C over pre-industrial levels and to limit it to under 2 degrees C) and will “[address] implementation of current nationally determined contributions, national adaptation plans and adaptation communications, including those submitted as adaptation components of nationally determined contributions, increase and accelerate ambition, and reflect the evolving needs of developing country Parties, and the need for enhanced provision and mobilization of climate finance from a wide variety of sources and instruments and channels”. On provision and mobilization , the draft provides three options with several sub-options. The options include: a direct provision and mobilization goal; a multi-layered approach, including investment, provision and mobilization: and a combination of the first two options. The mobilization goal has 6 sub-options. These sub-options have a very wide range -- from a NCQG of $100 billion to $1 trillion, $1.1 trillion, $1.3 trillion and $2 trillion, all per year, with the timeline being 2025-29 in one case, 2025-30 in another, 2025-35 in a third, 2026-30 in a fourth, and, simply, by 2030 in a sixth. The draft also suggests that developed countries provide at least $441 billion a year as grant, although there are options in terms of whether this will be part of the goal or in addition to it. The draft shows that pretty much every option is on the table. It also shows the very wide, polarized views on NCQG”. Meanwhile, New York Times correspondents David Gelles and Brad Plumer wrote, “The language of world leaders speaking on Tuesday at the United Nations climate summit was diplomatic, but the underlying message was clear: There’s friction over the big issue at the conference. The negotiations are focused on delivering a new plan to provide developing countries with funds to adapt to a warming world. Ali Mohamed, Kenya’s climate envoy, said there was widespread agreement that cutting emissions and making countries more resilient to storms, floods and heat would require “trillions” of dollars. But just days into the talks, there were pointed comments from the leaders and squabbling in the negotiating rooms about the details, including exactly how much money should be raised, who should pay, where it should come from and how it should be spent. “How? Where? By whom?” said Mr. Mohamed, the lead negotiator for the African group of countries. “That’s the discussion that’s currently underway.” The financing goal is meant to replace an annual target of $100 billion that was set in 2009 and finally met two years late, in 2022”. Elsewhere, Guardian correspondents Adam Morton, Fiona Harvey, Patrick Greenfield, Dharna Noor and Damian Carrington reported, “Major rich countries at UN climate talks in Azerbaijan have agreed to lift a global financial offer to help developing nations tackle the climate crisis to $300bn a year, as ministers met through the night in a bid to salvage a deal. The Guardian understands the Azeri hosts brokered a lengthy closed-door meeting with a small group of ministers and delegation heads, including China, the EU, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, the UK, US and Australia, on key areas of dispute on climate finance and the transition away from fossil fuels. It came as the COP29 summit in Baku, which had been due to finish at 6pm Friday, dragged into Saturday morning. A plenary session had been planned for 10am but did not eventuate….Multiple sources said the EU and several members of the umbrella group of countries including the UK, US and Australia had indicated they could go to $300bn in exchange for other changes to a draft text released on Friday. The Guardian understands that the UN secretary general, António Guterres, was ringing round capitals to push for a higher figure. Japan, Switzerland and New Zealand were understood to be among the countries resistant to the $300bn figure late on Friday. A $300bn offer would still fall well short of what developing countries say is necessary, and would likely draw sharp criticism if included in an updated text expected later on Saturday. But with some ministers booked to leave Baku in the hours ahead, countries face a decision on what they are prepared to accept. Several ministers from rich nations have argued that a deal may be easier now than next year, when Donald Trump will be US president and right-wing governments could be returned at elections in several countries, including Germany and Canada, and they do not want to make a commitment they cannot meet”.

US climate envoy John Podesta and deputy envoy Sue Biniaz, head into an elevator at Cop29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, after the climate summit went past its scheduled finish time. Photo: Joshua A Bickel/AP. |

As COP29 wrapped up in later November, many news stores assessed the outcomes as well as shortcomings. For example, New York Times journalist Brad Plumer wrote, “When this year’s United Nations climate summit in Baku, Azerbaijan, ended on Sunday, most developing countries and climate activists left dissatisfied. They had arrived at the summit on Nov. 11 with hopes that wealthy nations would agree to raise the $1.3 trillion per year that experts say is needed to help poor countries shift to cleaner energy sources and cope with extreme weather on a warming planet. The final deal was more of a muddle. After several bitter all-night fights, rich countries promised to provide $300 billion per year by 2035, an increase from current levels, but well short of what developing countries had asked for. The deal also laid out an aspirational goal of $1.3 trillion per year, though that target depends on private sector funding and left plenty of unresolved questions for future talks. The new agreement “is a joke,” one delegate from Nigeria said. Tina Stege, climate envoy for the Marshall Islands, was only slightly more measured: “It isn’t nearly enough, but it’s a start,” she said. “Countries seem to have forgotten why we are all here. It is to save lives.” A few commentators suggested that the funding deal was the best anyone could have hoped for, given that President-elect Donald Trump is about to pull the United States out of global climate agreements, while Europe is dealing with its own geopolitical turmoil. But the main reaction was disappointment. I’ve now covered six of these U.N. climate summits as a reporter, starting in 2017, and they often finish with attendees feeling ambivalent, if not angry. Governments spend the final hours deadlocked over how best to fight global warming and they usually compromise by watering down language — promises to “phase out” coal get softened to “phase down,” for instance — and by saying they’ll try to do better at future summits. Tina Stege walks down a hallway filled with various people and members of the news media at COP29. “It isn’t nearly enough, but it’s a start,” said Tina Stege, climate envoy for the Marshall Islands, right. “Countries seem to have forgotten why we are all here. It is to save lives.” One big reason that U.N. climate talks often seem maddeningly incremental is that, by design, they depend on voluntary cooperation among nations with wildly different interests, from big oil producers like Saudi Arabia to small islands menaced by sea-level rise. There’s no global authority that can force countries to act if they don’t want to. It’s a genuinely hard coordination problem. The theory behind the landmark Paris climate agreement, backed by every country in 2015, was that voluntary public commitments by nations would eventually spur greater action. Through peer pressure, countries would realize it was in their self-interest to shift to cleaner energy sources like wind, solar and nuclear power and help each other adapt to droughts and floods to avoid mass migration and widespread chaos. Whether that process is working depends on whom you ask…maybe there has been some progress, but it’s too slow. The window is quickly closing to keep warming at relatively low levels”. Meanwhile, New York Times journalist Max Bearak wrote, “Negotiators at this year’s United Nations climate summit struck an agreement early on Sunday in Baku, Azerbaijan, to triple the flow of money to help developing countries adopt cleaner energy and cope with the effects of climate change. Under the deal, wealthy nations pledged to reach $300 billion per year in support by 2035, up from a current target of $100 billion. Independent experts, however, have placed the needs of developing countries much higher, at $1.3 trillion per year. That is the amount they say must be invested in the energy transitions of lower-income countries, in addition to what those countries already spend, to keep the planet’s average temperature rise under 1.5 degrees Celsius. Beyond that threshold, scientists say, global warming will become more dangerous and harder to reverse. The deal struck at the annual U.N.-sponsored climate talks calls on private companies and international lenders like the World Bank to cover the hundreds of billions in the shortfall. That was seen by some as a kind of escape clause for rich countries. As soon as the Azerbaijani hosts banged the gavel and declared the deal done, Chandni Raina, the representative from India, the world’s most populous country, tore into them, saying the process had been ‘stage managed’”.

Barges are fully loaded with coal on the Mahakam River in Samarinda, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Photo: Dita Alangkara/AP. |

Elsewhere in November, at the G20 meeting held concurrently in Brazil, Indonesia’s President made news by declaring that all coal-fired power plants would be retired in the country within the next 15 years. For example, Associated Press correspondent Victoria Milko wrote, “Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto has announced that his government plans to retire all coal and other fossil fuel-power plants while drastically boosting the country’s renewable energy capacity in the next 15 years. “Indonesia is rich in geothermal resources, and we plan to phase out coal-fired and all fossil-fueled power plants within the next 15 years. Our plan includes building over 75 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity during this time,” Subianto said at the summit of leaders of the Group of 20 major economies in Brazil…Subianto also said he was “optimistic” Indonesia would achieve net zero emissions by 2050, a decade sooner than the country’s previous 2060 commitment. Experts and environmental activists welcomed the announcements but hedged their expectations. Indonesia is one of the world’s largest producers and consumers of heavily polluting coal and most of its energy comes from fossil fuels. Over 250 coal-fired power plants are currently powering the country and more are being built, including at new industrial parks where globally-important materials like nickel, cobalt and aluminum are being processed. In 2022, Indonesia’s energy sector emitted over 650 million tons of carbon dioxide, the world’s seventh highest level, according to the International Energy Agency. Population and economic growth are expected to triple the country’s energy consumption by 2050. Experts said that real changes need to be implemented on the ground in Indonesia quickly if the president is serious about his plans”.

However, media coverage of climate change or global warming in November was not merely all about politics, economics and policy. Several November stories also dealt with primarily scientific themes. For example, a Nature Communications Earth & Environment study about private aviation generate news attention. For example, Associated Press journalist Seth Borenstein reported, “Carbon pollution from private jets has soared in the past five years, with most of those small planes spewing more heat-trapping carbon dioxide in about two hours of flying than the average person does in about a year, a new study finds. About a quarter million of the super wealthy — worth a total of $31 trillion — last year emitted 17.2 million tons (15.6 million metric tons) of carbon dioxide flying in private jets, according to Thursday’s study in the Nature journal Communications Earth & Environment. That’s about the same amount as the 67 million people who live in Tanzania, Private jet emissions jumped 46% from 2019 to 2023, according to the European research team that calculated those figures by examining more than 18.6 million flights of about 26,000 airplanes over five years. Only 1.8% of the carbon pollution from aviation is spewed by private jets and aviation as a whole is responsible for about 4% of the human-caused heat-trapping gases, the study said”.

England’s footballers Conor Gallagher, Conor Coady and Declan Rice suffer during training in Qatar before the 2022 World Cup. Photo: Tom Jenkins/The Guardian. |

Elsewhere, a Scientific Reports study by Katarzyna Lindner-Cendrowska, Kamil Leziak, Peter Bröde, Dusan Fiala & Marek Konefał about climate change-related heat stress and 2026 World Cup soccer matches earned news attention. For example, Guardian correspondent Ajit Niranjan reported, “Footballers face a “very high risk of experiencing extreme heat stress” at 10 of the 16 stadiums that will host the next World Cup, researchers have warned, as they urge sports authorities to rethink the timing of sports events. Hot weather and heavy exercise could force footballers to endure temperatures that feel higher than 49.5C (121.1F) in three North American countries in 2026, according to the study. It found they are most at risk of “unacceptable thermal stress” in the stadiums in Arlington and Houston, in the US, and in Monterrey, in Mexico. The co-author Marek Konefal, from Wroclaw University of Health and Sport Sciences in Poland, said World Cups would increasingly be played in conditions of strong heat stress as the climate got hotter. “It is worth rethinking the calendar of sporting events now.” Football’s governing body, FIFA, recommends matches include cooling breaks if the “wet bulb” temperature exceeds 32C. But scientists are concerned the metric underestimates the stress athletes experience on the pitch because it considers only external heat and humidity. “During intense physical activity, huge amounts of heat is produced by the work of the player’s muscles,” said Katarzyna Lindner-Cendrowska, a climate scientist at the Polish Academy of Sciences and lead author of the study. “[This] will increase the overall heat load on the athlete’s body.” To overcome this, the researchers simulated temperatures that account for the players’ speed and activity levels, as well as their clothing. They were only partly able to include the effects of exercise in the heat index”.

Moreover, media portrayals in November also primarily covered ecological and meteorological stories. To begin, extremely harmful local pollution levels in Delhi, India – with several connections made to a warming planet – generated attention. For example, CNN journalists Esha Mitra, Aishwarya S Iyer and Helen Regan reported, “Inside Delhi’s first ever clinic dedicated to pollution-related illnesses, Deepak Rajak struggles to catch his breath. The 64-year-old’s asthma has worsened in recent days, and his daughter rushed him to the clinic, anxious about his rapidly deteriorating health. Sitting in the waiting room, Rajak tells CNN he has become “very breathless” and cannot stop coughing. “It’s impossible to breathe. I just came by bus, and I felt like I was suffocating,” he says. The specialist clinic at Delhi’s Ram Manohar Lohiya (RML) hospital was set up last year to treat the growing number of patients affected by hazardous air pollution, which worsens every winter in the Indian capital. Outside, a throat-searing blanket of toxic smog has settled over the city since late last month, turning day into night, disrupting flights, blocking buildings from view and endangering the lives of millions of people. As of last week, nowhere else on the planet has air so hazardous to human health, according to global air quality monitors. It’s become so bad that Delhi’s Chief Minister Atishi, who goes by one name, declared a “medical emergency” as authorities closed schools and urged people to stay home. But that’s not an option for Rajak, who relies on his dry-cleaning job to provide for his family. “What can I do? I have to leave the house to go to work,” he says. “If I don’t earn money, how will I eat? When I leave the house, my throat gets completely jammed. By evening it feels like I am lifeless.” Rajak has already been hospitalized once this year as the smog aggravated his asthma. With no relief in sight from the hazardous pollution, his daughter Kajal Rajak says she fears he will need to be readmitted – an added financial burden when they’re already struggling to pay for inhalers and expensive diagnostic tests. Even taking her father to the clinic was dangerous, she says. “You can’t see what’s in front of you,” Kajal says. “We were at the bus stop, and we couldn’t even see the bus number, or whether a bus is even coming – that’s how hazy it was.” In some parts of Delhi this week, pollution levels exceeded 1,750 on the Air Quality Index, according to IQAir, which tracks global air quality. A reading above 300 is considered hazardous to health. On Wednesday, the reading for the tiniest and most dangerous pollutant, PM2.5, was more than 77 times higher than safe levels set by the World Health Organization. CNN has reached out to the Indian Ministry of Forest Environment and Climate Change for comment. When inhaled, PM2.5 travels deep into lung tissue where it can enter the bloodstream, and has been linked to asthma, heart and lung disease, cancer, and other respiratory illnesses, as well as cognitive impairment in children”.

Commuters step out in a foggy winter morning amid rising air pollution in Greater Noida, on the outskirts of Delhi. Photo: Sunil Ghosh/Hindustan Times/Getty Images. |

Also, the official end of the Atlantic hurricane season at the end of the month produced several accounts of connections between climate change, global warming and the 18 named storms including Beryl, Helene, Milton and Rafael. For example, Associated Press correspondents Isabella O’Malley and Mary Katherine Wildeman reported, “The 2024 Atlantic hurricane season comes to a close Saturday, bringing to an end a season that saw 11 hurricanes compared to the average seven, and death and destruction hundreds of miles from where storms came ashore on the U.S. Gulf Coast. Meteorologists called it a “ crazy busy ” season, due in part to unusually warm ocean temperatures. Eight hurricanes made landfall, in the U.S., Bermuda, Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Grenada….Planet-warming gases like carbon dioxide and methane released by transportation and industry are causing oceans to rapidly warm. Several factors contribute to the formation of hurricanes, but unusually warm oceans allow hurricanes to form and intensify in places and times we don’t normally anticipate, McNoldy said. “In other words, we never had a storm as strong as Beryl so early in the season anywhere in the Atlantic and we never had a storm as strong as Milton so late in the season in the Gulf of Mexico,” he said. “I don’t ever point to climate change as causing a specific weather event, but it certainly has its finger on the scale and makes these extreme storms more likely to occur,” said McNoldy”.

Finally, November 2024 media representations also contained cultural-themed stories relating to climate change or global warming. For example, the devastating floods events in the region around Valencia, Spain generated several news accounts that made connections with climate change and global warming. For example, Guardian correspondent Cash Boyle noted, “Spaniards have taken to the streets of Valencia to demand the resignation of the regional president who led the emergency response to the recent catastrophic floods that killed more than 200 people. Floods that began on the night of 29 October have left 220 dead and nearly 80 people still missing. Residents are protesting over the way the incident was handled, with regional leader Carlos Mazón under immense pressure after his administration failed to issue alerts to citizens’ mobile phones until hours after the flooding started. The Valencian government has been criticised for not adequately preparing despite the State Meteorological Agency warning five days before the floods that there could be an unprecedented rainstorm. Tens of thousands of people made their dismay known by marching in the city on Saturday. The official attendance was estimated to be about 130,000. Some protesters clashed with riot police in front of Valencia’s city hall at the start of their march to the seat of the regional government, with police using batons to push them back…Concern about the risk of flooding in the region is not new. Members of Compromís, a leftwing alliance in the Valencian regional parliament, presented a proposal designed to tackle the issue in September 2023, but it was voted down by the government. Eva Saldaña of Greenpeace Spain has suggested that oil and gas companies “foot the bill” for this natural disaster, arguing that those industries have known about the climate crisis for more than six decades”.

And relating to the politics of COP29 as they met cultural dimensions of social movements for climate action, Swedish activist Greta Thunberg was quoted in many media stories about climate change in the month of November. For example, Washington Post correspondents Maxine Joselow, Chico Harlan, Julie Yoon and Joyce Lau reported, “Roughly 100 world leaders are traveling to Baku, Azerbaijan, for the U.N. Climate Change Conference — even as scores are skipping the annual talks, known this year as COP29. In a Tuesday address before world leaders speak at the summit, U.N. Secretary General António Guterres described the previous year as a “master class in climate destruction,” adding, “The sound you hear is the ticking clock.” He also expressed optimism about the transition to clean energy, saying that “no group, no business and no government” can stop it. Swedish activist Greta Thunberg chose to skip the conference: Speaking Monday at a protest in Tbilisi, Georgia, she called the summit’s host Azerbaijan “an authoritarian petrostate” and added that the choice of location was “beyond absurd””.

Figure 4. Examples of newspaper front pages with climate change stories in November 2024.

- report prepared by Max Boykoff, Rogelio Fernández-Reyes, Ami Nacu-Schmidt, Jeremiah Osborne-Gowey and Olivia Pearman