Why Can’t We All Just Get Along?

|

|

| The CSTPR blog, Prometheus, was revived in 2016 to regularly feature content from CSTPR core faculty, research associates, postdocs, visitors, students and affiliates to serve as a resource for science and technology decision makers. This new dynamism reflects the new energies and pursuits taking place in and around CSTPR. Below we feature one of the recent Prometheus blog posts. | |

|

|

The Colorado River weaves through the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico, providing water for over 40 million people, 5.5 million acres of irrigated farmland, and countless environmental and recreational assets along the way (United States Bureau of Reclamation 2012). Images of the mighty Colorado rushing through steep desert canyons and filling massive storage reservoirs can make the river’s flow seem limitless. In reality, however, the Colorado River is largely over-allocated, meaning that more water has been promised to users than typically flows down the river each year (Kenney 2009). Now, climate change and a rapidly growing human population are exacerbating water shortages in the region, making the development of effective strategies to manage the Colorado River one of today’s most pressing challenges. Conversations about water management in the American west tend to start from the same premise: here, “whiskey is for drinking, and water is for fighting” (United States Bureau of Reclamation 2017). As there’s less of the Colorado River to go around for the diverse users that depend on it, greater conflict seems imminent. Threats of impending “water wars” over the Colorado have become so forged into the region’s collective mindset that they’ve started to show up as plotlines for popular dystopian fiction novels, like Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife. |

|

Fortunately, a core group of public and private water professionals, academics, journalists, and river enthusiasts have started to push back against these narratives of insurmountable conflict. In an attempt to find a more sustainable answer to the region’s water woes, these folks are promoting management approaches that help stakeholders find common ground and incorporate the flexibility necessary to cope with greater water supply variability. Although their specifics vary, these approaches hold a core tenet in common: any good solution must incentivize people to share, collaborate, and negotiate creatively rather than divisively (Fleck 2016; Limerick 2016). Called collaborative governance processes by academics, such approaches typically convene diverse stakeholders to build trust, share knowledge, and develop consensus-oriented management actions (Ansell and Gash 2008; Emerson et al. 2012; Gerlak et al. 2013). While these approaches may require more time and financial resources than traditional, top-down policymaking processes, scholars and practitioners alike claim that they can generate more legitimate management strategies that result in greater resource sustainability with widespread benefits. |

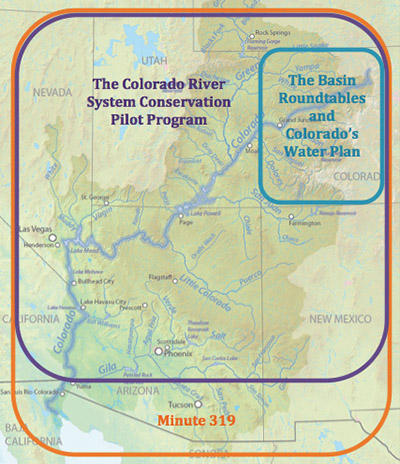

Approximate areas of the collaborative processes in the Colorado River Basin (background map of “Colorado River”). |

Collaborative governance experiments have begun to crop up across the Colorado River Basin. For instance, the state of Colorado recently led a 10-year “basin roundtable” process in which diverse stakeholders collaboratively assessed their water needs and potential solutions, leading to the production of Colorado’s first statewide water plan. Across the basin, four water providers and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation collaboratively developed and funded the Colorado River System Conservation Pilot Program, which financially incentivizes voluntary water conservation actions to raise water levels in the region’s major reservoirs. Collaboration has even caught-on internationally: in 2012, the U.S. and Mexico signed a landmark agreement that outlined pilot collaborative actions for better managing the transboundary river while also reviving the desiccated Colorado River Delta. Determining the effects of these programs and policies will ultimately require a test of time. For now, however, they suggest that collaboration is a promising - and necessary - alternative to the “water is for fighting” mindset that has dominated Colorado River management for so long. This post is based on research conducted by Dr. Elizabeth Koebele for her dissertation project “Collaborative Water Governance in the Colorado River Basin: Understanding Coalition Dynamics and Processes of Policy Change.” References United States Bureau of Reclamation, 2012. “Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study: Executive Summary.” Kenney, D., 2009. “The Colorado River: What prospect for “a river no more”?” In River Basin Trajectories: Societies, Environments, and Development, ed. F. Molle and P. Wester. Wallingford, U.K.: Cab International. 123-46. United States Bureau of Reclamation, 2017. “Whiskey is For Drinking, Water is for Fighting!”, (January 23, 2017). Fleck, J., 2016. Water is for fighting over: and other myths about water in the west. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. Limerick, P. N., 2016. Ditch in time: the city, the west and water. Golden, Co: Fulcrum Publishing. Ansell, C. and A. Gash, 2008. “Collaborative governance in theory and practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4):543-71. Emerson, K., T. Nabatchi, and S. Balogh, 2012. “An integrative framework for collaborative governance.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22 (1):1-29. Gerlak, A., T. Heikkila, and M. Lubell, 2013. “The promise and performance of collaborative governance.” In Oxford Handbook of U.S. Environmental Policy, ed. S. Kamieniecki and M. E. Kraft. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 413-34. |

|