Long Live the Linear Model

April 19th, 2006Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

Scholars who study the role of science in society have long dismissed the so-called “linear model” of science as descriptively inaccurate and normatively undesirable. In fact, within this community, such discussions are often viewed as pretty old stuff. However, when it comes to practicing scientists and many policy makers, the knowledge of the science studies crowd seems pretty far removed.

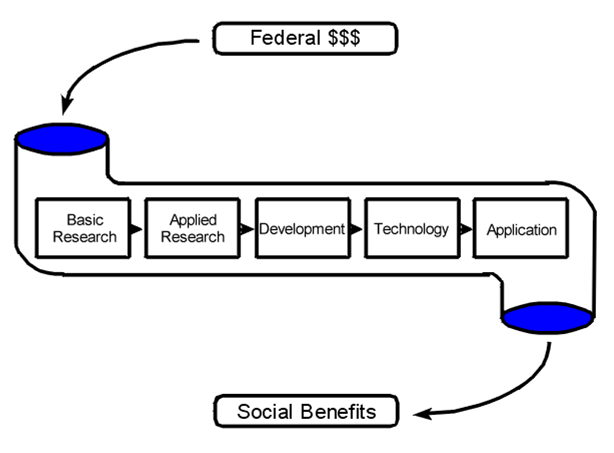

The linear model holds that investments in basic research are necessary and sufficient to stimulate scientific advancements, motivate technology developments, and bring products and serves to the market, where society benefits. The linear model was championed in Vannevar Bush’s post-war science policy manifesto titled “Science: the Endless Frontier” and has been fundamental to modern science policy ever since. Here is a graphic I made up illustrating the linear model.

I am reminded almost daily at the depths to which the linear model shapes science policy, science advocacy, and science politics. Yesterday I came across an op-ed which used the linear model to argue for increased funding, at an exponential rate it seems, for health research, based on the linear model. Here is an excerpt:

In 2002, roughly one-third of the papers were from US research groups. By 2004, US groups accounted for only one-quarter of the publications. Government policy may be among the factors contributing to the gap between US and international publications in the field.

Why worry about this trend? The answer lies with our biomedical ”discovery machine,” which operates on a seven-step assembly line:

1.) An academic scientist designs an experiment to answer an important question.

2.) The scientist applies to the government to fund the research.

3.) The money pays for students and fellows who conduct the research.

4.) The results are published in journals, which advance the field.

5.) An invention may result. This may lead to a patent, which then is licensed to a start-up company.

6.) With a monopoly granted by the patent, the company attracts venture capital. If it is successful, the company grows.

7.) Years later, the discovery becomes a therapy for patients.

It takes $28.8 billion, the annual budget of the NIH, to prime this machine. Every year, the money generates an astonishing amount of fundamental knowledge and thousands of biomedical discoveries. With no initial funding, this apparatus stops at Step 1.

With no money, what do the scientists do? They choose other careers. Worse, they leave to do research in other countries.

When scientists abandon their laboratories, a field can vanish. A scientific discipline is designed to grow exponentially. A professor will train a handful of students, some of whom go on to become professors and train more students. Some PhDs enter industry, where they lead projects and hire more trained workers. Funded properly, this collection of specialists becomes a formidable force, building research centers, driving innovation, and creating business sectors. The government front-loads the process; ingenuity and free enterprise takes care of the rest.

Scientists often get quite worked up when scientific knowledge is mispresented in the media, and rightly so. However, it seems that the bar is set quite a bit lower when it comes to the (mis)representation of knowledge from science studies.

April 19th, 2006 at 1:47 pm

Roger-

You seem to use “linear model” in two ways … one situation is when people argue that getting the science right on an issue will compel a certain policy outcome. We can both agree that’s bunkum.

The other quite different situation is described in this post. On this point, we might disagree, since I tend to believe that basic research does have value to society. Are you arguing that nothing of value ever results from basic research, or just that there’s a more efficient way to achieve benefits to society than basic research?

Finally, your last statement:

Scientists often get quite worked up when scientific knowledge is mispresented in the media, and rightly so. However, it seems that the bar is set quite a bit lower when it comes to the (mis)representation of knowledge from science studies.

is somewhat ambiguous. Are you criticising your fellow STS-ers for not mounting a more vigorous defense of your area? If that’s not it, who are you criticizing?

Regards.

Regards.

April 19th, 2006 at 2:14 pm

Andrew-

Thanks for your comments. A few replies:

1. Of course basic research has value. I would simply argue, as many scholars have, that the linear model is not a particularly effective basis for science policy decision making.

2. You are right that I use the linear model in 2 ways, but I view one as a subset/cousin of the other.

3. Have a look at this paper:

Pielke, Jr., R.A., and R. Byerly, Jr., 1998: Beyond Basic and Applied. Physics Today, 51(2), 42-46.

http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/admin/publication_files/resource-166-1998.12.pdf

4. You ask, “Are you criticising your fellow STS-ers for not mounting a more vigorous defense of your area? If that’s not it, who are you criticizing?”

I see your point. But I am criticizing both STSers for not speaking out more authoritatively, but also I am criticizing people who advocate theories of science policy without actually taking the time to determine if those theories are in fact accurate. I can imagine that I’d be pretty well taken to task if I wrote an op-ed in which I suggested a theory of climate change simply grounded in my suppositions!

Thanks!

April 19th, 2006 at 2:47 pm

The linear model emphasized here is a perception that scientific and/or technical knowledge can only be generated from basic research through applied research and/or development. Said another way, knowledge can only be generated along this linear path. The perceived value comes from the assertion that scientific research is privileged because it is the primary source of subsequent scientific and technical knowledge.

I’d characterize the other linear model more as a cousin than a subset, mainly because one model is dealing with knowledge generation, and the other with policy decision making (I also think the linear policy model is not as relevant outside of “science for policy” issues, which are only part of science and technology policy).

The key assumption in linking the models is that science policy decisions can (and should) be decided just like scientific research questions. Even if you agree with that assumption (which I do not), you can still criticize the linear models as being simplistic and broadly ignorant about much of the process of developing and codifying scientific knowledge.

STS scholars have dealt with both linear models. For work countering or criticizing the linear model of research, look at any work studying the development of research fields, especially in engineering. Anthropological or ethnographic work like Latour’s Laboratory Life also deal with the linear research model. Roger is right to point out that the criticisms of the linear research model have been well established within STS. The field has done a lousy job of communicating with other fields, much less those outside academe, to communicate their work.

For STS work dealing with the linear model of science policy development (get the science settled first, then you can deal with policy) look at scholars involved in boundary work. In STS this is usually focused on the boundary between science and pseudoscience (folk medicine, ufology, etc.), but it is applicable to the science/policy boundary danced around on this site. Some of David Guston’s work focuses on this boundary.

April 19th, 2006 at 8:01 pm

David- Thanks, you said this much better than I did!

April 20th, 2006 at 5:46 am

Leaving aside the linear model, there’s a pernicious mercantilism in the sentiment that for scientists to go abroad in search of funds is more damaging than them leaving science completely. Come to think of it, though, maybe that’s a necessary corollary of teh linear model as used in this sort of rhetoric.

April 28th, 2006 at 2:54 pm

Abram Reese Tristin Bernard Philip Jamal