In the current issue of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society John Knox concludes (PDF):

. . . if the projections are accurate: the number of undergraduate meteorology degree recipients will increasingly exceed the number of meteorology employment opportunities into the next decade. Thus, given recent trends and future projections, the growth of the U.S. undergraduate meteorology population is potentially unsustainable in terms of bachelor’s degree–level employment within meteorology.

With respect to the job market for meteorologists he finds another solid indication of a glut:

Meteorology graduates’ salaries in this national database are much closer to those in the traditionally glutted and underpaid humanities fields than to salaries for graduates with computer science, physics, geology, or mathematics degrees.

Knox indicates that this situation has developed because the atmospheric sciences community has ignored the demand side of the equation when pressing for an ever increasing supply of students, and may foreshadow a similar glut at the graduate level:

the quantitative results of this article can be construed to indicate that we have entered

a period of chronic oversupply of undergraduate meteorologists. This oversupply has arguably come about because the mechanisms that generate interest in our field (e.g., unprecedented media emphasis on weather) are mostly uncoupled to the mechanisms of demand. Media coverage of weather and climate topics can inspire throngs of students to pursue meteorology as a career; it is specifically cited by UNC Charlotte meteorologists as a reason for their program’s spectacular growth (www.charlotte.

com/274/story/103334.html). But widespread media attention does not magically create future employment opportunities for these students within meteorology. If, in turn, this situation translates into a future boom in graduate school enrollments and Ph.D. production, the current parlous state of “grantsmanship” in our science as described by the critiques of Carlson (2006) and Roulston (2006) would seem tame by comparison.

In the same issue, Jeff Rosenfield, Editor-in-Chief of BAMS editorializes (not online, at p. 773) that he was “surprised” by the data. He should not have been. In 2002 I engaged in a series of exchanges on the pages of BAMS on exactly this question in response to a paper by Vali, Anthes, et al. warning of a shortage of PhD atmospheric scientists. They argued that one solution was to boost the undergraduate ranks in the atmospheric sciences:

we as a community should seek ways to increase the number of qualified applicants. Because the number of atmospheric scientists required under any reasonable scenario is small compared to the total number of students in undergraduate education, a modest increase in the effort to recruit students from other disciplines could have a major impact in a relatively short period of time.

In response, I argued that any discussion of a shortfall in supply of atmospheric sciences professionals needed also to be accompanied by some understanding of the market demand for people trained with this expertise, something that Vali , Anthes, et al. neglected to discuss, and Knox identifies as a root factor in the present mismatch of supply and demand. I argued that the atmospheric sciences were risking committing the exact same mistake made by the NSF when it proclaimed a looming shortage of scientists in the 1990s. I concluded:

The science and technology community generally experienced loss of credibility in the 1990s when a number of prominent figures claimed a looming shortage of scientists. Leaders in the atmospheric sciences are in a position to use experience to avoid such errors in future assessments of the labor market. In particular, considerable care must be taken in raising expectations of potential students and policymakers about the future prospects for employment.

In reply, Vali and Anthes dismissed the importance of any consideration of demand, raised the “idealistic” vision of the free pursuit of knowledge, and ended with a jingoistic appeal to the need for more native U.S. scientists. To this I rejoined that there was indeed data available that portended a potential oversupply of atmospheric scientists, and this data was ignored at some risk. No one should be surprised at the current labor market situation for atmospheric scientists.

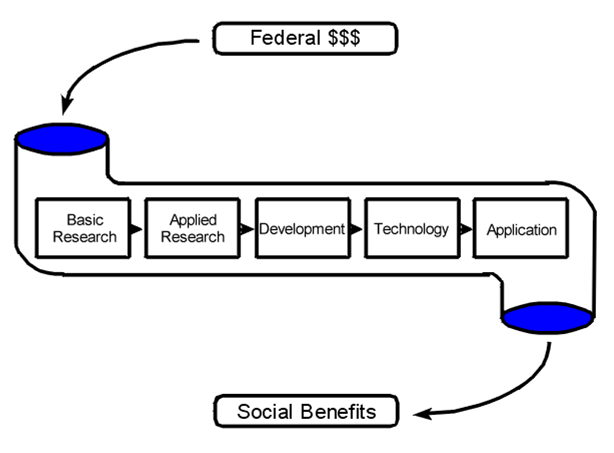

Now it turns out that the community faces an oversupply of undergraduates, depressed salaries, and a potential loss of credibility. Of course, the entirely predictable next step in this situation will be for the atmospheric sciences community to bemoan the fact that research budgets have not kept pace with the supply of trained atmospheric scientists, and call for an increase in federal R&D to create new opportunities. And in this way, the politics of science funding go round and round.