Did you know that today is “World Malaria Day“? I wouldn’t be surprised if you didn’t; a search of Google News shows 233 stories on “world malaria day” published in the past 24 hours. A search of “climate change” over the past 24 hours shows 45,819 stories. This post is about the inevitable conflict in objectives that results when we frame the challenge of global warming in terms of “reducing emissions” rather than “energy modernization.” The result is inevitably a battle between mitigation and adaptation, when in reality they should be complements.

Why does malaria matter? According to Jeffrey Sachs:

The numbers are staggering: there are 300 to 500 million clinical cases every year, and between one and three million deaths, mostly of children, are attributable to this disease. Every 40 seconds a child dies of malaria, resulting in a daily loss of more than 2,000 young lives worldwide. These estimates render malaria the pre-eminent tropical parasitic disease and one of the top three killers among communicable diseases.

The Economist reported a few weeks ago on efforts to eradicate malaria. The article referenced a study by McKinsey and Co. on the “business case” (PDF) for eradicating malaria. Here are the reported 5-year benefits:

• Save 3.5 million lives

• Prevent 672 million malaria cases

• Free up 427,000 hospital beds in sub-Saharan Africa

• Generate more than $80 billion in increased GDP for Africa

I want to focus on the prospects for increasing African GDP, for as we have learned via the Kaya Identity, an increase in GDP will necessarily mean an increase in carbon dioxide emissions. So what are the implications of eradicating malaria for future greenhouse gas emissions from Africa?

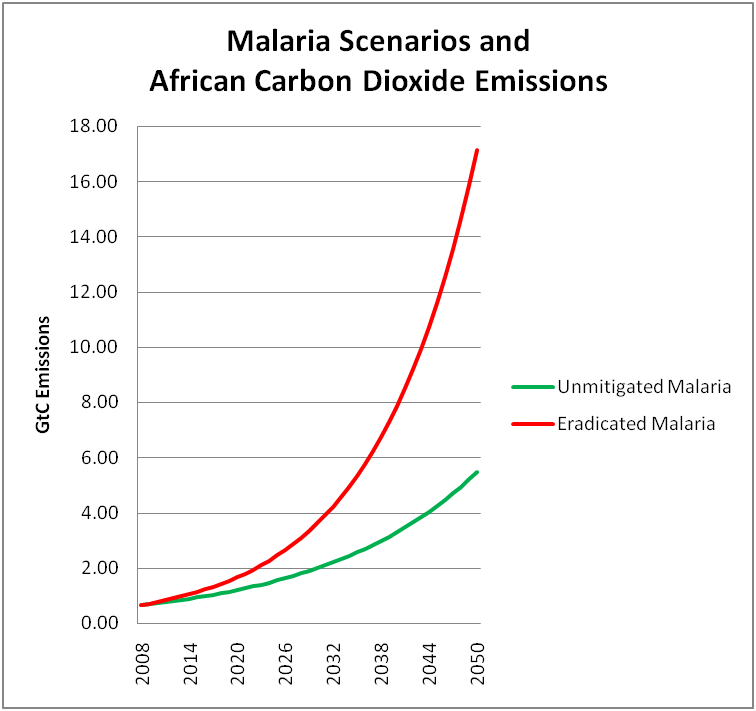

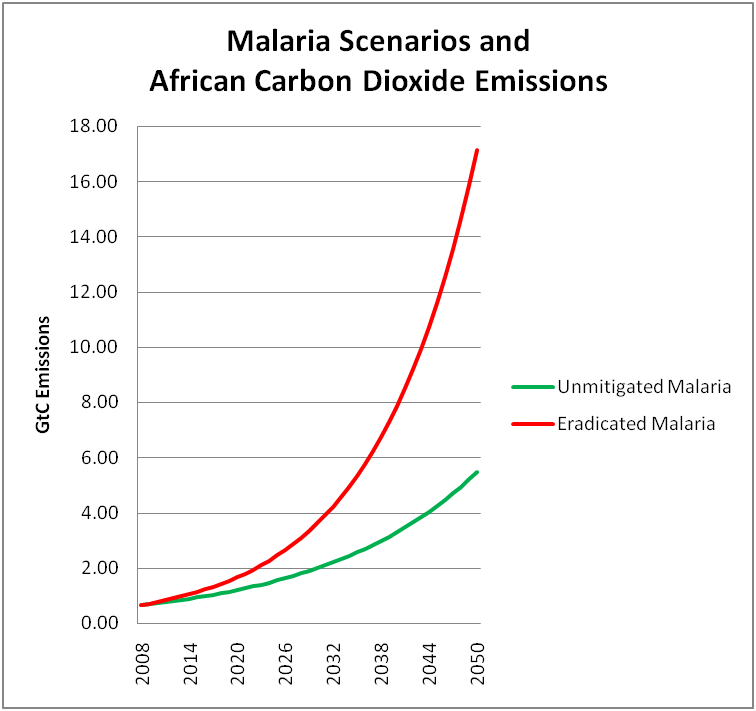

To answer this question I obtained data on African greenhouse gas emissions from CDIAC, and I subtracted out South Africa, which accounts for a large share of current African emissions. I found that the average annual increase from 1990-2004 was 5.2%, which I will use as a baseline for projecting business-as-usual emissions growth into the future.

The next question is what effect the eradication of malaria might have on African GDP. The McKinsey & Co. report referenced a paper by Gallup and Sachs (2001, link) which speculates (and I think that is a fair characterization) that complete eradication could boost GDP growth by as much as 3% per year. This would take African emissions growth rates to 8.2%, which is still well short of what has been observed in China this decade, and thus not at all unreasonable. So I’ll use this as an upper bound (not as a prediction, to be clear). So if we graph future emissions under my definition of business-as-usual and also the Gallup/Sachs upper bound, we get the following curves to 2050.

The figure shows that by eradicating malaria, it is conceivable that there will be an corresponding increase in annual African emissions of more than 11 GtC above BAU. Today, the entire world has about 9 GtC. For those following our debate with Joe Romm earlier this week, this would mean that he would have to come up with another way to get 10 more “wedges,” as rapid African growth is included in none of the BAU emissions scenarios. Put another way, the success of his proposed policies depends on not eradicating malaria since rapid African GDP growth busts his wedge budget.

The implications should be obvious: If a goal of climate policy is simply to “reduce emissions” then this goal clearly conflicts with efforts to eradicate malaria, which will inevitably lead to an increase in emissions. But if the goal is to modernize the global energy system — including the developing the capacity to provide vast quantities of carbon-free energy, then there is no conflict here.

This distinction helps to explain why there persists an adaptation vs. mitigation debate, and why it is that advocates of adaptation (to which eradicating malaria falls under) are often excoriated as “deniers” or “delayers” — adaptation just doesn’t help the emissions reduction challenge. The continued denigration of those who support adaptation will continue until we reframe the climate debate in terms of energy modernization and adaptation, which are complementary approaches to sustainable development.

Over at The New Scientist Fred Pearce takes a broader view and warns of “green fascism” on the issue of development and population:

But there is another question that I find increasingly being asked. Should we be trying to stop others having babies, especially people in poor countries with fast-growing populations?

I must say I thought this kind of illiberal thinking had been banished from the environmental movement. But it keeps seeping back. When I give public talks on climate change, I am often asked if all the efforts in the rich world won’t be wiped out by rising populations in the poor world.

Isn’t overpopulation more dangerous than overconsumption? I say no. But the unpalatable truth is that a lot of environmental thinking over the past half century has been underpinned by an unhealthy preoccupation with the breeding propensity of Asians and Africans. . .

Only recently, US groups opposed to all migration tried to get their policies adopted by the blue-chip environment group, the Sierra Club. To many they sounded like a fringe group. Actually they were an echo of the earlier mainstream.

And the echo is becoming louder. We hear it in the climate change debate. No matter that the average European or North American has carbon emissions 10 times greater than the average Indian or African, somehow it is those pesky breeding foreigners who are really to blame.

And now food shortages are growing and we will get more. Ehrlich, we are bound to be told, was right after all. You have been warned: green fascism could soon be on the march.

It is long overdue to rethink how we think about the climate debate.