Why Costly Carbon is a House of Cards

June 12th, 2008Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

How can the world achieve economic growth while at the same time decarbonizing the global economy?

This question is important because there is apt to be little public or political support for mitigation policies that increase the costs of energy in ways that are felt in reduced growth. Consider this description of reactions around the world to the recent increasing costs of fuel:

Concerns were growing last night over a summer of coordinated European fuel protests after tens of thousands of Spanish truckers blocked roads and the French border, sparking similar action in Portugal and France, while unions across Europe prepared fresh action over the rising price of petrol and diesel. . .

Protests at rising fuel prices are not confined to Europe. A succession of developing countries have provoked public outcry by ordering fuel price increases. Yesterday Indian police forcibly dispersed hundreds of protesters in Kashmir who were angry at a 10% rise introduced last week. Protests appeared likely to spread to neighbouring Nepal after its government yesterday announced a 25% rise in fuel prices. Truckers in South Korea have vowed strike action over the high cost of diesel. Taiwan, Sri Lanka and Indonesia have all raised pump prices. Malaysia’s decision last week to increase prices generated such public fury that the government moved yesterday to trim ministers’ allowances to appease the public.

Advocates for a response to climate change based on increasing the costs of carbon-based energy skate around the fact that people react very negatively to higher prices by promising that action won’t really cost that much. For instance, our frequent debating partner Joe Romm says of a recent IEA report (emphasis added):

. . . cutting global emissions in half by 2050 is not costly. In fact, the total shift in investment needed to stabilize at 450 ppm is only about 1.1% of GDP per year, and that is not a “cost” or hit to GDP, because much of that investment goes towards saving expensive fuel.

And Joe tells us that even these “not costly” costs are “overestimated.”

If action on climate change is indeed “not costly” then it would logically follow the only reasons for anyone to question a strategy based on increasing the costs of energy are complete ignorance and/or a crass willingness to destroy the planet for private gain. Indeed, accusations of “denial” and “delay” are now staples of any debate over climate policy.

There is another view. Specifically that the current ranges of actions at the forefront of the climate debate focused on putting a price on carbon in order to motivate action are misguided and cannot succeed. This argument goes as follows: In order for action to occur costs must be significant enough to change incentives and thus behavior. Without the sugarcoating, pricing carbon (whether via cap-and-trade or a direct tax) is designed to be costly. In this basic principle lies the seed of failure. Policy makers will do (and have done) everything they can to avoid imposing higher costs of energy on their constituents via dodgy offsets, overly generous allowances, safety valves, hot air, and whatever other gimmick they can come up with.

Analysts and advocates allow this house of cards to stand when trying to sell higher costs of energy to a skeptical public they provide analyses that support a conclusion that acting to cut future emissions is “not costly.”

The argument of “not costly” based on under-estimating the future growth of emissions so that the resulting challenge does not appear so large. We have discussed such scenarios on many occasions here and explored their implications in a commentary in Nature (PDF).

One widely-know example is the stabilization wedge analysis of Stephen Pacala and Robert Socolow (PDF. The stabilization wedge analysis concluded that the challenge of stabilizing emissions was no so challenging.

Humanity already possesses the fundamental scientific, technical, and industrial know-how to solve the carbon and climate problem for the next half-century. A portfolio of technologies now exists to meet the world’s energy needs over the next 50years and limit atmospheric CO2 to a trajectory that avoids a doubling of the preindustrial concentration. . . But it is important not to become beguiled by the possibility of revolutionary technology. Humanity can solve the carbon and climate problem in the first half of this century simply by scaling up what we already know how to do.

In a recent interview the lead author of that paper, Pacala provided a candid and eye-opening explanation of the reason why they wrote the paper (emphases added):

The purpose of the stabilization wedges paper was narrow and simple – we wanted to stop the Bush administration from what we saw as a strategy to stall action on global warming by claiming that we lacked the technology to tackle it. The Secretary of Energy at the time used to give a speech saying that we needed a discovery as fundamental as the discovery of electricity by Faraday in the 19th century.

We also wanted to stop the group of scientists that were writing what I thought were grant proposals masquerading as energy assessments. There was one famous paper published in Science [Hoffert et al. 2002] that went down the list [of available technologies] fighting them one by one but never asked “what if we put them all together?” It was an analysis whose purpose was to show we lacked the technology, with a call at the end for blue sky research.

I saw it as an unhealthy collusion between the scientific community who believed that there was a serious problem and a political movement that didn’t. I wanted that to stop and the paper for me was surprisingly effective at doing that. I’m really happy with how it came out – I wouldn’t change a thing.

That doesn’t mean that there aren’t things wrong with it and that history won’t prove it false. It would be astonishing if it weren’t false in many ways, but what we said was accurate at the time.

So lets take a second to reflect on what you just read. Pacala is claiming that he wrote a paper to serve a political purpose and he admits that history may very well prove its analysis to be “false.” But he judges the paper was successful not because of its analytical soundness, but because it served its political function by severing relationship between a certain group of scientific experts and decision makers whose views he opposed.

Why is this problematic? NYU’s Marty Hoffert has explained that the Pacala and Socolow paper was simply based on flawed assumptions. Repeating different analyses with similar assumptions doesn’t make the resulting conclusions any more correct. Hoffert says (emphases added):

The problem with the formulation of Pacala and Socolow in their Science paper, and the later paper by Socolow in Scientific American issue that you cite, is that they both indicate that seven “wedges” of carbon emission reducing energy technology (or behavior) — each of which creates a growing decline in carbon emissions relative to a baseline scenario equal to 25 billion tonnes less carbon over fifty years — is enough to hold emissions constant over that period. . . .

A table is presented in the wedge papers of 15 “existing technology” wedges, leading virtually all readers to conclude the carbon and climate problem is soluble with near-term technology; and so, by implication, a major ramp-up of research and development investments in alternate energy technology like the “Apollo-like” R&D Program that we call for, is unnecessary. . . .

The actual number of wedges to hold carbon dioxide below 450 ppm is about 18, not 7, for Pacala-Socolow scenario assumptions, as Rob well knows; in which case we’re much further from having the technology we need. The problem is actually much worse than that, since the number of emission-reducing wedges needed to avoid greater than two degree Celsius warming explodes after the mid-century mark if world GDP continues to grow three percent per year under a business-as-usual scenario.

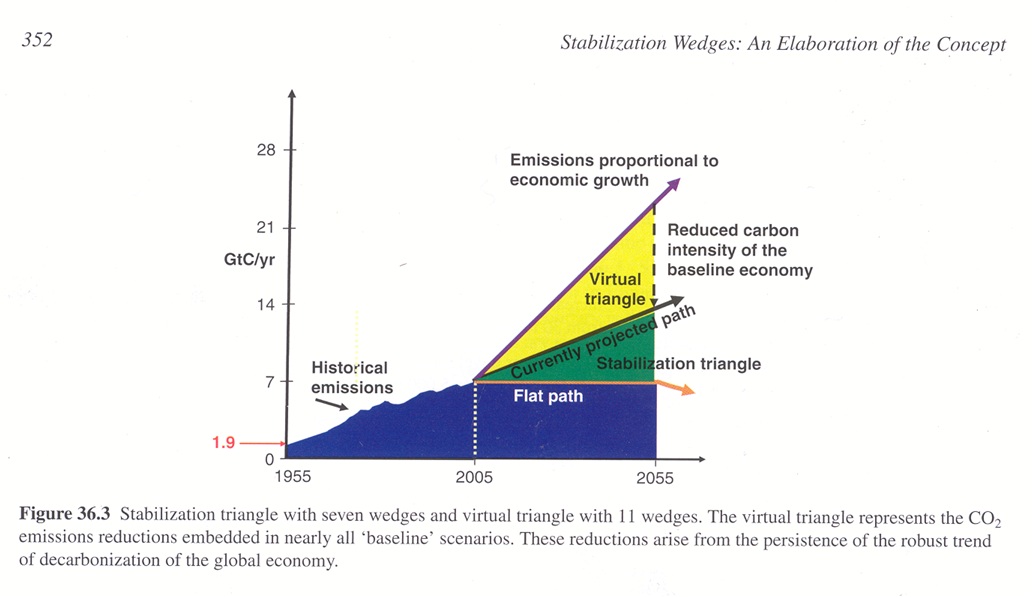

The figure below is from a follow-on paper by Socolow in 2006 (PDF) and clearly indicates the need for 11 additional wedges of emissions reductions from 2005 to 2055. These are called “virtual wedges” which is ironic, because their existence is very real and in fact necessary for the stabilization of emissions to actually occur. (Cutting emissions by half would require another 4 wedges, or 22 total).

If Pacala and Socolow admit that we need 18 wedges to stabilize emissions, and 22 wedges to cut them by half, and this is based on an rosy assumption of only 1.5% growth in emissions to 2055, then why would anyone believe that we need less? If it is conceivable that emissions might grow faster than 1.5% per year, then we will need even more than the 22 wedges. Perhaps much more. But analysts seeking to impose a price on carbon won’t tell you this. Instead, some will resort to demagoguery, and others will simply repeat over and over again the consequences of assuming rosy scenarios. None of this will make the mitigation challenge any easier. But as Pacala says in the excerpt above, such strategies may keep more sound analyses out of the debate.

Policies based on the argument that putting a price on carbon will be “not costly’ are a house of cards, and based on a range of assumptions that could easily be judged very optimistic. Looking around, what you will see is that the minute that energy prices rise high enough to be felt by the public, action will indeed occur, but it will not be the action that is desired by the climate intelligencia. It will be demands for lower priced energy. And policy makers will listen to these demands and respond. Climate policy analysts should listen as well, because there will be no tricking of the public with rosy scenarios built on optimistic assumptions.

June 12th, 2008 at 12:42 am

According to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Bartlett, Albert Bartlett is an emeritus Professor of Physics at the University of Colorado at Boulder. He has made it abundantly clear why economic growth in a finite world is unsustainable. Why, then, would a sincere scientist premise his thesis with the assumption of continued economic growth. Certainly, the world’s poorest economies should grow but only at the expense of economic shrinkage in the developed nations. In the articles on energy at http://dematerialism.net/, I have shown that only through political economic change can a sustainable society be achieved. In any case, it appears that we are now past the Hubbert Peak for world petroleum production. Thus, the scarcity of energy should prevent economic growth except for predatory imperialistic nations and perhaps not even in them.

Tom Wayburn, Houston, Texas

June 12th, 2008 at 10:04 am

I’m trouble with what Pacala said in the interview for several reason:

“I saw it as an unhealthy collusion between the scientific community who believed that there was a serious problem and a political movement that didn’t.”

First, is the case for mitigation so weak that scientist have to manipulate the fact to convince people to act.

Second, how scientific is it when the conclusion is reach before the experiment is done.

Third, how different is it to what Hansen said that people needed to be scared into taking GW seriously in the early 90s.

Finally, if mitigation cost/benefit ratio was high than who would opposed mitigation. I don’t have a lot of money and I always ask this question what do I have to gain by paying more of my limited income on energy? This will not help me invest in more efficient insulating technologies or newer more efficient car.

Another fact that would be funny if it wasn’t so sad. In Québec, almost all the electricity comes from hydro, nuclear and wind turbines except about 2-3% that comes from oil plant. A few years back there were plans to build a new last generation oil plant to replace an aged one. The new plant would have produce much less CO2 than the old one. Environmentalist opposed the project which cause the project to be abandoned and the old inefficient plant to be repaired.

June 12th, 2008 at 11:06 am

This discussion conflates cost and price responses. The cost of mitigation is the actual changes in allocations of resources undertaken to produce a different outcome. A carbon tax or cap & trade system raises the price of carbon. That induces costly action on the part of carbon consumers, but a component of the price is a transfer of resources. Whether that transfer is benign (e.g. a lump sum rebate) or not (a gift to shareholders of existing emitters) makes a big difference.

The time trajectory of implementation also matters. Truckers are rioting (and BBQ users aren’t) because fuel prices have risen quickly compared to the scale and lifespan of their assets and commitment to their career. (Also, the wealth transferred by high prices does not get broadly distributed.) If changes had occurred more gradually, with clear expectations, and softened by redistribution of the proceeds, the outcome might be quite different.

It does seem likely that the public will continue to demand lower-priced energy. Responding to that by promising to deliver same through R&D is about as delusional as promising that mitigation won’t be costly. There may be small free lunches either way, but not on the scale needed to solve the problem. The difference is that the public finds out about price-induced mitigation costs now, but only discovers that R&D fails to deliver, or gets consumed by rebound effects, much later.

The public wants much more than low energy prices. They also want higher income, for example. Yet we’ve had broad income taxes for a long time. Those induce large transfers, but they also presumably induce real, costly allocation changes. The externalities targeted (education or income distribution perhaps) are if anything more controversial than climate. This suggests that it’s not impossible to undertake costly measures with uncertain payoffs. It might take a long time, either to learn from experience or achieve some kind of paradigm shift, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that we should give up.

June 12th, 2008 at 11:27 am

“Finally, if mitigation cost/benefit ratio was high than who would opposed mitigation.”

Even if the aggregate benefit/cost ratio is favorable, there will always be narrower groups who face different tradeoffs. Carbon intensive industries, people with high discount rates, etc. have an incentive to avoid controls (unless you devise a compensation scheme to change that, e.g. grandfathering permits).

“what do I have to gain by paying more of my limited income on energy? This will not help me invest in more efficient insulating technologies or newer more efficient car.”

This is exactly the cost-price or allocation-distribution conflation I mentioned. When OPEC cuts production and oil prices rise, you and I face a real loss, especially in the short term because it’s hard to modify consumption. But if the change in energy prices occurs via a self-imposed transfer that reemerges broadly in the economy, the result is rather different. If you don’t have much money, and thus don’t consume much energy anyway, you could come out ahead under a rebated tax, because the rebate would exceed the increase in energy and conservation expenditures.

June 12th, 2008 at 3:18 pm

“If you don’t have much money, and thus don’t consume much energy anyway, you could come out ahead under a rebated tax,…”

What I find inconvenient is that there is no proposal that benefit the vast majority of people that are already using a limited amount of energy.

People in my situation are doing the most they can to reduce their energy cost. Even though my situation could be worst, my household income is low enough that we have to do everything we can to reduce our energy cost. For example, we are using compact fluorescent for any light that are regularly lighted and phasing the old bulb has they die. We set the heating temp in the low 70s during daytime and at 68 at night during the winter and we set the AC at 78 to 80 in the summer. We only use our car when necessary.

I would certainly not object any scheme that would reduce my load of energy cost. On the other I will not support anything that make it worst. We have a below average consumption and I do believe that those who are higher than average should pay more for there energy. Sadly, like I said earlier the proposal put the burden on everyone and not on the worst offender.

June 13th, 2008 at 3:10 pm

Roger — This would seem to be another one of your posts trying to convince people that achieving acceptable levels of carbon dioxide is hopeless.

I just don’t see how strategies that cost maybe 0.1% of GDP per year, which is where the IPCC and IEA seem to be, can be labeled “misguided and cannot succeed.”

You write, “the current ranges of actions at the forefront of the climate debate focused on putting a price on carbon in order to motivate action are misguided and cannot succeed.”

I couldn’t disagree more with that sentence, but in any case, it is impossible to debate you a since you never bother spelling out exactly what other options you would pursue that actually have any plausible chance of stabilizing concentrations at 450 to 500 ppm.

Needless to say, if your reanalysis of the wedges were right (and I have demonstrated that it isn’t, but let that go for now), then that ould be all the more reason to start deploying those wedges now and do so faster than five decades as I’ve been saying. If your reanalysis of the wedges were right, then a strategy based on hoping we might get multiple breakthrough technologies at some point in the future, which could somehow be deployed even faster than existing technologies could be deployed is patently hopeless.

I do agree that you seem to be conflating a carbon price with the overall cost of action. Your post seems to imply that action is simply too costly compared to the cost of inaction. Needless to say, I could not disagree with you more, nor could the IPCC, the IEA, the National Academies, and even most economists I know.

June 13th, 2008 at 8:46 pm

Mr Romm,

I suggest that you re-read the post since it seems that you didn’t understood it.

Roger position has always been clear that he support both mitigation and adaptation. I don’t agree with him on that point.

What I think you should understand from what Roger wrote is that by sugarcoating the cost of mitigation those, like you, who advocates strong action will only faced the deception of big talk and no action. What people like you should understand is that if you want to succeed you need to be upfront about the real cost and not paint a rosy picture that the public will not buy or want.

I think one of the best example of the big talk and no action strategy is the UK that are speaking loud enough while acting the opposite.

June 17th, 2008 at 3:49 am

Mr Romm:

Dr Pielke and many others are pointing out why the campaign to increase fuel costs is not a viable “ option” ” with a “plausible chance of stabilizing concentrations at 450 to 500 ppm”. And to point this out is laudable because doing nothing is preferable to doing something stupid.

But you say to Dr Pielke;

“it is impossible to debate you a since you never bother spelling out exactly what other options you would pursue that actually have any plausible chance of stabilizing concentrations at 450 to 500 ppm.”

However, that presupposes there is an “option” with a “plausible chance of stabilizing concentrations at 450 to 500 ppm”. There may be such an “option” but to date none has been evinced and at present it is not possible to devise one.

Only those who believe that it is necessary and/or desirable to stabilise concentrations at “450 to 500 ppm” have a responsibility to suggest workable methods to achieve that. And they have a problem in making such a suggestion because there is no known relationship between anthropogenic emissions and atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide.

Stating this problem in the words of the IPCC

“no systematic analysis has published on the relationship between mitigation and baseline scenarios”

(ref. IPCC Third Assessment Report (2001) Working Group 3 Chapter 2”

Richard S Courtney

June 17th, 2008 at 3:52 am

Mr Romm:

Dr Pielke and many others are pointing out why the campaign to increase fuel costs is not a viable “option” with a “plausible chance of stabilizing concentrations at 450 to 500 ppm”. And to point this out is laudable because doing nothing is preferable to doing something stupid.

But you say to Dr Pielke;

“it is impossible to debate you a since you never bother spelling out exactly what other options you would pursue that actually have any plausible chance of stabilizing concentrations at 450 to 500 ppm.”

However, that presupposes there is an “option” with a “plausible chance of stabilizing concentrations at 450 to 500 ppm”. There may be such an “option” but to date none has been evinced and at present it is not possible to devise one.

Only those who believe that it is necessary and/or desirable to stabilise concentrations at “450 to 500 ppm” have a responsibility to suggest workable methods to achieve that. And they have a problem in making such a suggestion because there is no known relationship between anthropogenic emissions and atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide.

Stating this problem in the words of the IPCC

“no systematic analysis has published on the relationship between mitigation and baseline scenarios”

(ref. IPCC Third Assessment Report (2001) Working Group 3 Chapter 2”

Richard S Courtney

June 17th, 2008 at 7:21 pm

I’ve noticed that we’ve reacted to higher gas prices by driving even less efficiently.

June 17th, 2008 at 7:22 pm

Link: http://cumulativemodel.blogspot.com/2008/06/high-gas-prices-are-causing-high-gas.html

June 19th, 2008 at 9:17 pm

Roger, you’ve made some excellent points, though I think this remains confused.

1. It’s not that the cost-benefit and risk analyses that support efforts to price carbon are a house of cards, it’s the emissions rights givewaays and politician-directed pork-barrel “green technology” subsidies/grants, and the deceptive way in which these “solutions” are being marketed to us that is the house of cards.

Yes, we need carbon pricing, and yes increasing costs will have a particularly regressive bite, and it is wrong to sell this as easy rather than facing it honestly. It is also wrong to fail to note all of the eager feeding at the federal troughs that the latest climate bill anticipated – some $56 TRILLION in giveaways. I agree that if this is the type of climate policy that we are looking at, people will very quickly get fed up and demand lower prices – which might very well gut any benefit from cap and trade.

But it doesn’t need to be. Climate policy can be both sustainable AND fair – as long as it protects the interests of average Americans rather than sereving to feed the special interests of well-fed elites. What we need is either a carbon tax (or auctioned emission rights) with ALL PROCEED REFUNDED pro rata to citizens – as Jim Hansen has recently argued for, based on long-standing proposals of “Sky Trust ” advocate Peter Barnes and more recent proposals of Biddle and Boyle.

The tax and 100% dividend approach recognizes that the atmopshere is a public good – not something that fossil users have a primary claim to – would create long-term support for climate policy by allowing consumers to pay for the higher costs they face, even while providing incentives to change behavior, and would minimize pork barrel rent-seeking.

2. “How can the world achieve economic growth while at the same time decarbonizing the global economy?”

“[T]here is apt to be little public or political support for mitigation policies that increase the costs of energy in ways that are felt in reduced growth.”

These are misguided. CBA tells us that pricing carbon makes sense now – because GDP “growth” is an inadequate measure that ignores the damage done to important and valuable assets that are unowned and unpriced. Rather, there is likely to be little long-term support for climate mitigation policies if the burden of such policies is not fairly shared, but shifted to lower and middle class consumers. Revenue recycling will remove the sting.

3. Pacala’s “wedge” approach is perfectly appropriate. Citizens should understand that our problems are not unsurmountable – at least, that it, if we have the political will to address them.

Regards,

Tom