The New Global Growth Path

June 16th, 2008Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

A very important new paper is forthcoming in the journal Climatic Change which has been published first online. The paper is:

P. Sheehan, 2008. The new global growth path: implications for climate change analysis and policy, Climatic Change (in press).

The paper argues that:

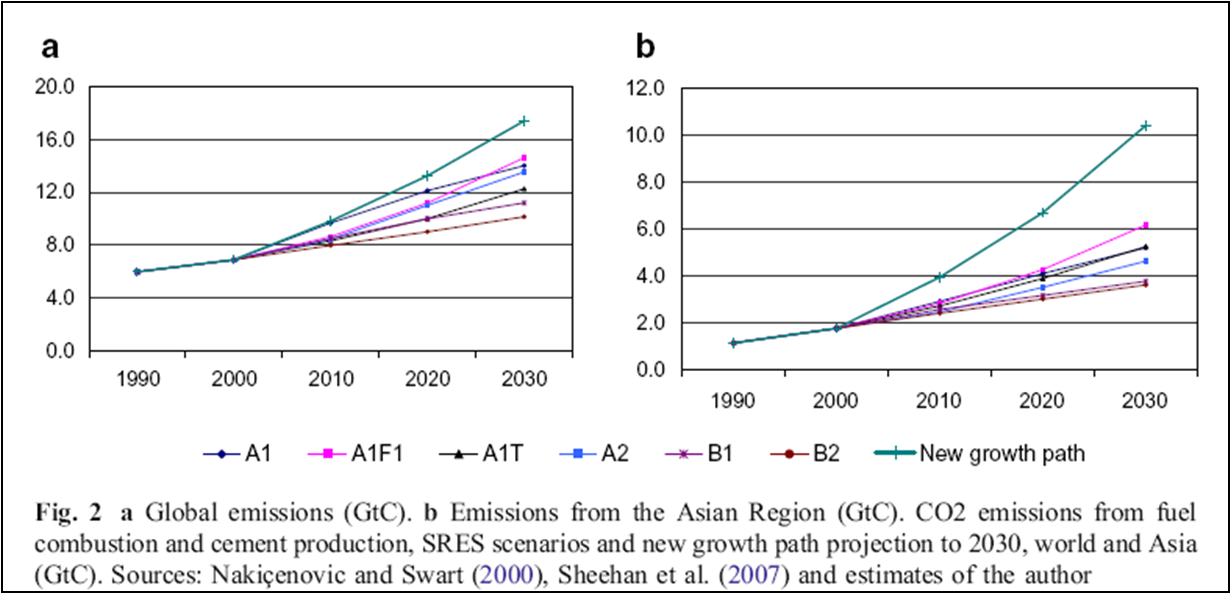

In recent years the world has moved to a new path of rapid global growth, largely driven by the developing countries, which is energy intensive and heavily reliant on the use of coal—global coal use will rise by nearly 60% over the decade to 2010. It is likely that, without changes to the policies in place in 2006, global CO2 emissions from fuel combustion would nearly double their 2000 level by 2020 and would continue to rise beyond 2030. Neither the SRES marker scenarios nor the reference cases assembled in recent studies using integrated assessment models capture this abrupt shift to rapid growth

based on fossil fuels, centred in key Asian countries.

This conclusion strongly supports the analysis that we presented in Nature (PDF)not long ago, in which we argued that the mitigation challenge was potentially underestimated in the so-called IPCC SRES (and pre- and post- SRES) scenarios due to overly aggressive assumptions about future trends in the decarbonization of the global economy. Such overly optimistic assumptions are endemic in the literature, found in the Stern Review, and IEA and CCSP assessments, among others.

Sheehan comes to similar conclusions:

To the extent that NGP is a reasonable projection of global trends on current policies out to 2030, it follows that all of the SRES marker scenarios seriously understate unchanged policy emissions over that time, and do so because they do not capture the extent of the expansion in energy use and emissions that is currently taking place in Asia. Nor, as a consequence, do they capture the rapid growth in coal use that is also occurring. . .

The SRES scenarios were a substantial intellectual achievement, and have stood the test of time for almost a decade. But the central feature of global economic trends in the early decades of the twenty-first century—the new growth path shaped by the sustained emergence of China and India, in the context of an open, knowledge-based world economy—could not be foreseen in the 1990s, and is not covered by these scenarios. Many of the SRES scenarios are no longer individually plausible, and as a whole the marker scenarios can no longer be said to ‘describe the most important uncertainties’. As a result, and especially given the emissions intensity of the new growth path, there is an urgent need for new approaches.

Unfortunately, a major obstacle to discussing (much less achieving) new approaches are the very public intellectual and political commitments that have been advanced, based on the earlier assumptions. Unwinding these commitments — as we have seen — will take some doing.

PS. See also the NYTs Andy Revkin and Elisabeth Rosenthal on China’s growing emissions here. As yet, the dots remain to be connected between such trends unfolding before our eyes and their incongruity with assumptions in energy policy assessments. But reality and policy assessments can diverge only for so long.

June 16th, 2008 at 6:45 am

So CO2 concentrations have increased much faster than anticipated since 2000.

Yet during that same time, there has been no increase in temperature? Perhaps even a decrease in temperature?

Doesn’t this news on CO2 present a challenge to those who are predicting serious problems, if not out right disasters?

June 16th, 2008 at 8:55 am

Roger:

I’m not sure if it supports your analysis in the Nature paper, but it certainly undermines the conclusions.

What we need now is very aggressive deployment of efficient and low-carbon energy technologies nationally and globally, — that is the “new approach” we need. This paper makes clear yet again we can’t stick with the old, old approach of hoping and wishing for TILTs (Terrific Imaginary Low-carbon Technology).

Also, for reasons I have previously explained, this paper does not substantially change the number of wedges of existing and near-term technology we need:

http://climateprogress.org/2008/04/23/is-450-ppm-politically-possible-part-25-the-fuzzy-math-of-the-stabilization-wedges/

That said, given the stunning recent rise in oil prices (and indeed in all energy price4s), I think it quite imprudent to simply assume that the emissions path of the past several years will continue for decades. That is probably the one thing we can be confident won’t happen.

Joe

June 16th, 2008 at 9:49 am

Joe-

It is amazing that your calculation of needed wedges is apparently completely insensitive to future emissions trajectories. This is simply absurd. The amount of future emissions reductions needed is OF COURSE a function of future emissions. How can you argue otherwise?

The rise in oil prices may indeed reduce demand for oil, especially in OECD countries, but as you know many countries cap fuel prices and thus there is no market signal. To the extent that there is a market signal, some switching to coal might occur.

Again, I don’t now what future emissions will be, but I do know that our policies should be robust to possibilities.

June 16th, 2008 at 9:56 am

Joe-

You can’t have it both ways.

1. If your definition of “wedges” in fact refers to a 1.8 GtC reduction 50 years from now, then you are mistaken when you say we need 14 of them under your assumptions of future emissions growth — in fact we’d only need about 8 of them.

2. If your definition of wedges refers to a 1.0 GtC reduction 50 years from now, then you are mistaken when you say that we need 14 of them under Sheehan’s assumptions of future emissions growth — in fact we’d need about 30+ of them.

So which is it Joe? Have you overstated the challenge or understated the challenge? Or do you change answers and assumptions as is convenient?

More on this debate:

http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/prometheus/archives/energy_policy/001406joe_romms_fuzzy_mat.html

June 16th, 2008 at 2:11 pm

Roger,

I think its clear what he is saying.

Each wedge represents the replacement of energy infrastructure that “would have existed 50 years from now” with green infrastructure.

To the extent that anticipated improvements to infrastructure that “would have existed” do not materialize, he says that it doesn’t matter because in his world this infrastructure will already have been replaced with cleaner alternatives.

It doesn’t matter how dirty coal technology is in 2058 if there are no coal power plants. The dirtier coal technology is, the more carbon is saved by the wedges that represent the replacement of coal energy with nuclear.

Of course its foolish to assume that there will be no coal power plants in 2058, but there could be dramatically fewer.

If we take his reasoning to its logical conclusion, it represents an interesting point of view.

What is the point of investing in carbon efficiency improvements for coal technology when all the coal plants will be replaced with non-fossil sources?

What is the point in conserving energy, when all our energy needs will be provided by non-fossil sources?

If we assume dramatic improvements in non-fossil energy sources over the next fifty years, then efforts to improve and economize our use of fossil energy sources will be rendered moot, and the vast resources spent on such efforts will be largely wasted.

Jason

June 16th, 2008 at 3:02 pm

solman- Thanks for your comments, I’m happy to let Joe respond on his own, but I’m pretty sure from our exchanges that he’d disagree with your following comments:

“What is the point of investing in carbon efficiency improvements for coal technology when all the coal plants will be replaced with non-fossil sources?

What is the point in conserving energy, when all our energy needs will be provided by non-fossil sources?”

June 16th, 2008 at 4:13 pm

I disagree with the following statement: “…the new growth path shaped by the sustained emergence of China and India, in the context of an open, knowledge-based world economy—could not be foreseen in the 1990s, and is not covered by these scenarios.” On the contrary, many who argued that Kyoto would be totally ineffective did so in part precisely because of the anticipated growth of emissions in China and India that have come to pass. Chalk up another one for those ‘head-in-the-sand’ skeptics. Looks like they were right once again!

There is a definite pattern emerging with the ‘science is settled’ crowd: they continue to overestimate the problem (“The end of the world is at hand!”), while underestimating the cost of their proposed solutions (“Rationing carbon will be good for the economy!”). This is also hardly surprising. That is the pattern that always emerges when a minority group or individual tries to exert control over the majority. The threat is always exaggerated. The cost of the solution is always downplayed.

What is most amazing is that so many continue to be surprised each time it happens!

June 16th, 2008 at 6:48 pm

Jim-

I don’t disagree on anticipated growth patterns — some of my colleagues have similar views. Though I would be interested in any specific references to contemporary predictions of recarbonization that you have in mind.

Thanks.

June 16th, 2008 at 7:35 pm

Nice try, Jason, except as Roger knows, you have my argument exactly backwards. Only massive investment in energy efficiency and low-carbon technology now, can avert catastrophe.

Now, it is basically the case that the higher the projected emissions growth compared to the Pacala/Socolow projection, the more coal intensive the growth was, and the more carbon each wedge averts. I don’t think concept is too complicated, but I take it no one but Roger actually read the link I posted above explaining it.

Unfortunately, with one exception, nobody, not Princeton, the IPCC, or even Pielke or the people he likes to quote, have actually ever bothered to publish a rigorous business-as-usual baseline. So it isn’t possible to say exactly how many wedges are needed. But my link above makes a pretty reasonable case that the number is around 14 — though as Roger knows, I think we need to deploy them in 4 decades, not 5, as Princeton does.

The only analysis I’ve seen with a baseline I think is credible is the recent IEA report, and they use the equivalent of 13 wedges to stabilize at around 450 ppm, close to what I have:

http://climateprogress.org/2008/06/10/iea-report-part-2-climate-progress-has-the-solution-about-right/

Now I don’t think that analysis is perfect, nor does Roger. But until Roger presents his own detailed baseline and his “solution,” merely sending potshots at other people’s analysis won’t be especially persuasive. For now, I stand by the best estimate of 13 to 14 wedges. I doubt the answer is fundamentally larger or fundamentally smaller.

June 16th, 2008 at 9:01 pm

Joe-

We have suggested using a “frozen technology baseline” as we argued in our Nature paper. the point is not that technology won’t change, but to lay out the full scope of the mitigation challenge, rather than hiding it behind assumptions. So there you have a rigorous, unambiguous baseline. I have explained that it implies (at least) twice the magnitude of emissions reductions from scenarios that assume various rates of spontaneous decarbonization.

Do you really believe that the amount of future emissions reductions required for stabilization is **insensitive** to the actual magnitude of future emissions? Seriously?

June 17th, 2008 at 7:04 am

“Only massive investment in energy efficiency and low-carbon technology now, can avert catastrophe.”

“until Roger presents his own detailed baseline and his ’solution’”

Like many others, you make this sound like a binary choice: Either we “solve the problem” or “face catastrophe”.

Isn’t this sort of argument likely to be turned on its head?

For most common definitions of “solve the problem”, (stabilization at 500ppm for example) a very compelling argument can be made that there is virtually no chance that the citizens of earth will accept the required sacrifices.

If I actually believed that this was a binary problem, I would already be preparing to “face the consequences”, and not want to waste any precious resources tilting at windmills.

Fortunately, I understand that each additional gigaton of emissions as some (highly uncertain) marginal cost associated with it, and I am prepared to address the problem as any sane person would, investing in those improvements which have a substantially greater benefit than cost.

June 17th, 2008 at 7:27 am

Joe,

It is not “sending potshots at other people’s analysis” to point out that a fundamental assumption in these studies is catastrophically flawed.

Unless you assume a nearly total replacement of fossil fuel generation with new technologies, the conclusions of these studies are EXTREMELY dependent on the rate at which carbon efficiency has been improving.

Right now, the world is becoming LESS carbon efficient, yet these studies assume that in the absence of climate policy there will be substantial annual improvements for the next 40 to 100 years.

If we make government investments now in cleaner fossil fuel technologies, and these assumed improvements do not materialize, then the investment will be wasted.

I don’t understand why you won’t admit this point.

June 17th, 2008 at 5:24 pm

Roger — I guess we’ll just have to agree to disagree, which is no surprise. Frozen technology is not a baseline of what would happen in the absence of climate policy. It is a theoretical construct, perhaps the only one we can be certain won’t actually happen in the real world.

You have posed an irrelevant question to our discussion — “Do you really believe that the amount of future emissions reductions required for stabilization is **insensitive** to the actual magnitude of future emissions? Seriously?”

As you know, the (secondary) issue is not whether future emissions reductions are insensitive to the magnitude of future emissions. The issue is whether the amount of low-carbon technology (the number of wedges) you need to deploy is insensitive to the magnitude of future emissions. As I have shown, that appears to be the case.

But the primary issue is, if the problem is indeed harder than everyone thinks, do we need to deploy existing and near-term technology faster or slower than we thought? Do you seriously think the answer is slower, as all your writing seems to imply?

Solman — I’m just going to ignore you because I have no idea what your core set of beliefs are. Either one believes in trying to limit warming to 2°C from preindustrial levels, as Roger and pretty much the entire scientific community does. Or not.

We don’t need any “assumed improvements” to achieve 450 ppm. We need massive deployment of existing and near-term clean energy technology, probably 13 to 14 wedges by 2050, if not sooner.