[UPDATED: See below]

Writing at the FT, London School of Economics economist William Buiter calls the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009 (otherwise known as Waxman-Markey) “a total con”:

[Under ACES] emissions will not be reduced. But that is inconsistent with the supposed desire to reduce emissions to 83 percent of their 2005 level by 2020 and to 17 percent of the 2005 level by 2050. Except that is it not inconsistent if there is no intention to reduce emissions at all, but instead every intention to permit them to be raised above their 2005 levels. And that is of course what is going on.

Here I go beyond Buiter’s cogent critique to add a few quantitative details to how offsets under the bill will allow emissions to rise essentially indefinitely.

First, lets start with some assumptions.

1. The scheme begins in 2012.

2. The scheme covers 85% of US emissions.

3. 85% of 2012 emissions are 6,078 million tonnes

4. The scheme has a goal of reducing emissions to 5,056 million tonnes by 2020 and 3,533 by 2030.

5. 2,000 tonnes of offset credits are available each year of the scheme

6. Unused offsets roll over and can be used in subsequent years

Under these assumptions we can reach a few interesting conclusions.

First, to achieve the 2020 emissions reduction goal under a scenario of 2.0% annual GDP growth requires decarbonization of the U.S. economy of about 4.0% per year. Under the faster rate of economic growth in the Obama Budget that rate of decarbonization needs to be 5.2% per year.

Second, to achieve the 2030 emissions reduction goal under a scenario of 2.0% annual GDP growth requires decarbonization of the US economy of about 5.0% per year. Under the faster rate of economic growth in the Obama Budget that rate of decarbonization needs to be 5.7% per year.

Since no one knows how to decarbonize an economy at rates of 4% or above per year over a period of decades, the authors of the ACES bill have provided the opportunity for the generous use of “offsets” — which means that credit can be claimed toward the ACES goals for reducing emissions (or more likely, reducing hypothetical future emissions) both inside and outside of the U.S. economy.

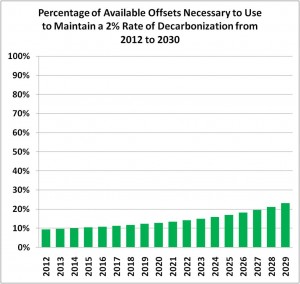

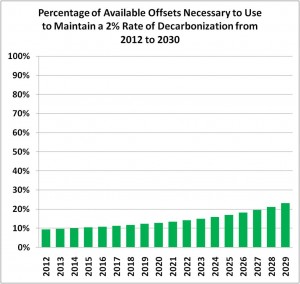

I was curious as to how many offsets would have to be used for the U.S. to maintain its historical rate of decarbonization of about 2% per year. So I have conducted the following exercise:

1. I projected US emissions at a 2% rate of decarbonization of the economy coupled with assumed economic growth of 2% per year.

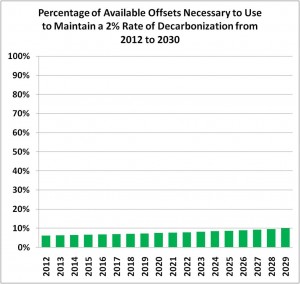

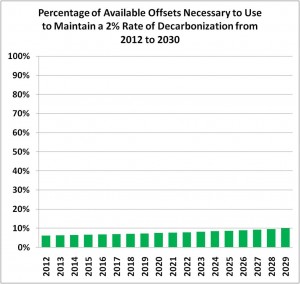

2. I then compared this scenario with emissions reductions consistent with the targets in ACES for 2020 and beyond. [UPDATE: The first version of the graph I showed below used a rate of decarbonization faster than required by ACES to 2020, but consistent with a 2030 trajectory, the second graph shows a rate consistent with the 2020 trajectory.]

3. I assume that the difference between the 2% decarbonization scenario and the ACES scenario will be made up for entirely through use of offsets.

The question I want to answer is, what percentage of available offsets would be necessary to use to sustain a 2% rate of decarbonization? The answer surprised me and can be seen in the following graph.

What this graph shows is that only a small portion of available offsets would need to be used to sustain the historical rate of decarbonization of the U.S. economy [UPDATE] consistent with the ACES 2030 trajectory. Economic modelers like to call this “business as usual.” Whether the 2% rate results from business as usual, the effects of ACES, or a combination of both is irrelevant to this exercise.

[UPDATE} The graph below shows the rate consistent with the 2020 emissions reduction trajectory. The rates are different to 2020 and 2030 under ACES, which is why the graphs look different

(Methodological notes: I ignore the phase in of covered entities from 2012 to 2016 under ACES, making my exercise a bit conservative. Using a faster rate of growth, such as under the Obama Budget would increase the values for 2020 by about 3%.)

What this exercise shows is that it it would be possible under an offsetting scheme like that in ACES to avoid achieving decarbonization rates of 4% or greater by using only a small fraction of available offsets, and thus do absolutely nothing to change, much less transform, the U.S. energy system. William Buiter is correct — offsets are a “con for our time.”