Staffing Cuts at NCAR: A Puzzle

August 19th, 2008Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

NCAR’s decision to terminate its CCB group has motivated some posts here focused on understanding the justifications given for the decision. One claim that we haven’t yet explored was put forward by UCAR’s Rick Anthes in a press release:

Over the past five years NCAR has had to lay off approximately 55 people and have lost another 77 positions due to attrition, totaling roughly 16% of NCAR positions, because of sub-inflationary NSF funding and decreases in other agency support.

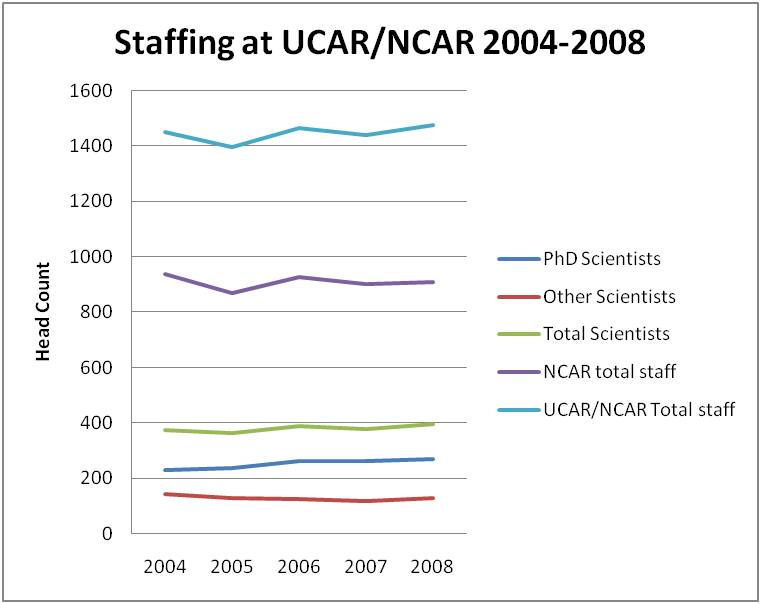

I have gone to the UCAR website and downloaded official reports (available here) on the staffing “head count” across its organization. The graph below shows this information for PhD scientists, other scientists (their category), total scientists (the previous two numbers together), total NCAR employment and total UCAR/NCAR employment. Note that for all years the data is as of September 30, except 2008 which is June 30 (about 7 weeks ago).

Some things to note about the data, and hence the puzzle hinted at in the title.

1. The number of UCAR/NCAR PhD scientists has increased 2004-2008 by 31, to 268, representing a 16% increase. Over the same period, the number of other scientists has decreased by 16, to 127, representing a 12% decrease. However, the 2008 value is identical to 2005, and 10 more than 2007.

2. The total number of scientists in the organization increased 2004-2008 from 374 to 395, representing a 6% increase.

3. The total staff in the NCAR division of UCAR decreased by 29 positions from 2004 to 2008 from 936 to 907. However, in 2005 the total was 868, so from 2005-2008 the headcount increased by 39 positions.

4. Overall, total UCAR/NCAR employment increased by 25 positions from 2004 to 2008, to 1477 employees. From 2005-2008 the increase was 80 positions.

So the puzzle is: where are these “lost” 142 positions? The official data from UCAR/NCAR on its “head count” do not reflect this large number of lost positions. In fact, they show that NCAR’s staff is 29 less than 2004 but 39 more than 2005 levels. The entire organization has grown since 2004, as its scientific staff has grown by 21 scientists.

Anyone care to resolve this puzzle?