Boulder Science Cafe, May 13th 5:30 RedFish

May 6th, 2008Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

May 13, 2008. Roger Pielke Jr. CIRES, CU Boulder. “Have we underestimated the Carbon Dioxide Challenge?” Details. RedFish, 5:30PM, 2027 13th Street.

Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

May 13, 2008. Roger Pielke Jr. CIRES, CU Boulder. “Have we underestimated the Carbon Dioxide Challenge?” Details. RedFish, 5:30PM, 2027 13th Street.

Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

The U.S. Congress has its own power plant which provides steam and cooled water to the various congressional buildings. This plant is powered powered by coal, which makes it a large obstacle in Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s (D-CA) goal of making the Congress carbon neutral. Thus, the power plant has been the subject of some political wrangling that has members of Congress from coal-producing states against those looking to avoid the hypocrisy of Congress calling for emissions limits while operating its own business in a carbon intensive manner.

Today the GAO released a report (PDF) on the costs associated with switching the plant from coal to natural gas. At first glance the costs are not terribly large — in 2009, the costs would be from $1.0 to $1.8 million, with the difference largely due to uncertainties in the costs of natural gas. GAO estimates that the switch would save 9,970 tons of carbon dioxide emissions from the case of no switch.

This equates to $370 to $650 per ton of carbon. This is far higher than the costs of carbon being considered in legislation, found in the market of in the ETS, an in the realm of the costs of simple air capture (PDF).

Now there is surely a lesson here, beyond the fact that members of Congress are willing to pay above market prices for policy outcomes. At these costs, the act of fuel switching at the Capitol power plant would clearly be only of symbolic value, but if emissions reductions can indeed be archived at a low cost, why would the Congress be paying up to $650 per ton of carbon? This doesn’t seem like the right message to be sending to the American public, and could potentially backfire.

Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

Did you know that today is “World Malaria Day“? I wouldn’t be surprised if you didn’t; a search of Google News shows 233 stories on “world malaria day” published in the past 24 hours. A search of “climate change” over the past 24 hours shows 45,819 stories. This post is about the inevitable conflict in objectives that results when we frame the challenge of global warming in terms of “reducing emissions” rather than “energy modernization.” The result is inevitably a battle between mitigation and adaptation, when in reality they should be complements.

Why does malaria matter? According to Jeffrey Sachs:

The numbers are staggering: there are 300 to 500 million clinical cases every year, and between one and three million deaths, mostly of children, are attributable to this disease. Every 40 seconds a child dies of malaria, resulting in a daily loss of more than 2,000 young lives worldwide. These estimates render malaria the pre-eminent tropical parasitic disease and one of the top three killers among communicable diseases.

The Economist reported a few weeks ago on efforts to eradicate malaria. The article referenced a study by McKinsey and Co. on the “business case” (PDF) for eradicating malaria. Here are the reported 5-year benefits:

• Save 3.5 million lives

• Prevent 672 million malaria cases

• Free up 427,000 hospital beds in sub-Saharan Africa

• Generate more than $80 billion in increased GDP for Africa

I want to focus on the prospects for increasing African GDP, for as we have learned via the Kaya Identity, an increase in GDP will necessarily mean an increase in carbon dioxide emissions. So what are the implications of eradicating malaria for future greenhouse gas emissions from Africa?

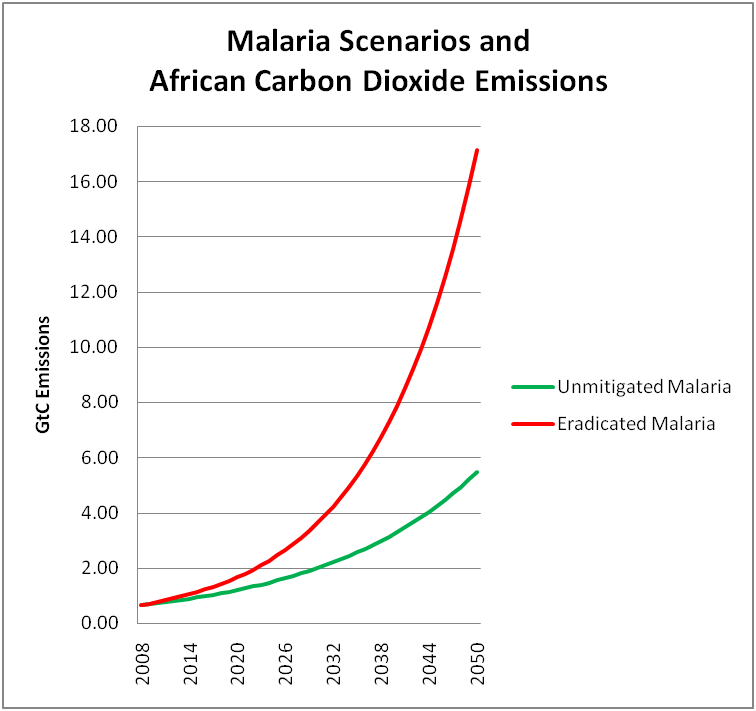

To answer this question I obtained data on African greenhouse gas emissions from CDIAC, and I subtracted out South Africa, which accounts for a large share of current African emissions. I found that the average annual increase from 1990-2004 was 5.2%, which I will use as a baseline for projecting business-as-usual emissions growth into the future.

The next question is what effect the eradication of malaria might have on African GDP. The McKinsey & Co. report referenced a paper by Gallup and Sachs (2001, link) which speculates (and I think that is a fair characterization) that complete eradication could boost GDP growth by as much as 3% per year. This would take African emissions growth rates to 8.2%, which is still well short of what has been observed in China this decade, and thus not at all unreasonable. So I’ll use this as an upper bound (not as a prediction, to be clear). So if we graph future emissions under my definition of business-as-usual and also the Gallup/Sachs upper bound, we get the following curves to 2050.

The figure shows that by eradicating malaria, it is conceivable that there will be an corresponding increase in annual African emissions of more than 11 GtC above BAU. Today, the entire world has about 9 GtC. For those following our debate with Joe Romm earlier this week, this would mean that he would have to come up with another way to get 10 more “wedges,” as rapid African growth is included in none of the BAU emissions scenarios. Put another way, the success of his proposed policies depends on not eradicating malaria since rapid African GDP growth busts his wedge budget.

The implications should be obvious: If a goal of climate policy is simply to “reduce emissions” then this goal clearly conflicts with efforts to eradicate malaria, which will inevitably lead to an increase in emissions. But if the goal is to modernize the global energy system — including the developing the capacity to provide vast quantities of carbon-free energy, then there is no conflict here.

This distinction helps to explain why there persists an adaptation vs. mitigation debate, and why it is that advocates of adaptation (to which eradicating malaria falls under) are often excoriated as “deniers” or “delayers” — adaptation just doesn’t help the emissions reduction challenge. The continued denigration of those who support adaptation will continue until we reframe the climate debate in terms of energy modernization and adaptation, which are complementary approaches to sustainable development.

Over at The New Scientist Fred Pearce takes a broader view and warns of “green fascism” on the issue of development and population:

But there is another question that I find increasingly being asked. Should we be trying to stop others having babies, especially people in poor countries with fast-growing populations?

I must say I thought this kind of illiberal thinking had been banished from the environmental movement. But it keeps seeping back. When I give public talks on climate change, I am often asked if all the efforts in the rich world won’t be wiped out by rising populations in the poor world.

Isn’t overpopulation more dangerous than overconsumption? I say no. But the unpalatable truth is that a lot of environmental thinking over the past half century has been underpinned by an unhealthy preoccupation with the breeding propensity of Asians and Africans. . .

Only recently, US groups opposed to all migration tried to get their policies adopted by the blue-chip environment group, the Sierra Club. To many they sounded like a fringe group. Actually they were an echo of the earlier mainstream.

And the echo is becoming louder. We hear it in the climate change debate. No matter that the average European or North American has carbon emissions 10 times greater than the average Indian or African, somehow it is those pesky breeding foreigners who are really to blame.

And now food shortages are growing and we will get more. Ehrlich, we are bound to be told, was right after all. You have been warned: green fascism could soon be on the march.

It is long overdue to rethink how we think about the climate debate.

Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

Der Spiegel has an excellent article on the future of Germany’s energy supply. Even with projections of a falling population, Germany has a looming gap between the energy it needs and the energy it projects to be available. Why is this? According to the article:

Nuclear power is too dangerous. Coal is too dirty. Gas involves too much dependence on Russia. And renewables are insufficient. So just where is Germany going to get its power from?

How did Germany, with its forward-thinking renewable policies and ecologically sensitive populace, get into this situation?

The problem is that up until now the Germans have been too passive in working towards achieving an energy supply that satisfies all requirements; in other words, one that is environmentally friendly, safe and cost-efficient at the same time. They have chosen to fritter away the fruits of their prosperity on day-to-day problems instead of investing them in intelligent preparations for the future — in other words, in energy research.

In fact, Germany actually offers the ideal conditions to achieve even more impressive technological advances than in the past. The Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), with its 7,500 staff, is a perfect illustration of this potential.

Engineers on the campus of the KIT are testing, for example, a prototype system that converts straw into fuel. In another lab, engineers are developing a highly efficient geothermal power plant, and in yet another, physicists are building giant magnets for the experimental ITER fusion reactor to be based in France.

Everywhere at KIT, solutions are being developed which will not only help Germany, but also the rest of the world, to overcome the most serious energy problems. But the engineers and scientists at the Karlsruhe technology park sense — precisely because they are so ambitious — the limits of what they can do. Peter Fritz, the institute’s head of research, says that the threat of an energy gap in Germany is not the only reason that “a great deal of know-how and money needs to be mobilized very quickly.”

In comparison to the size of the problem, energy research in Germany has tended until now to be somewhat relegated to the sidelines. But it is also a decisive weak point, including in the debate over the expected power shortfall. This is because cutting-edge research offers the best way to limit the costs associated with a massive expansion of renewable energy.

From a global perspective, government research expenditures have hardly increased since the early 1970s, and the situation is especially bleak in Germany. After the 1973 oil crisis, annual expenditures for energy research, adjusted for inflation, were almost doubled to €1.5 billion ($2.37 billion). But then, as the pressure of high oil prices subsided, research budgets were gradually reduced before reaching a record low of just under €360 million ($569 million) in 2001.

Energy research budgets have gone up again since then, but far too slowly. Ironically, the grand coalition makes no secret of its pride in having brought the government’s energy research budget back up to above €500 million ($790 million).

KIT research director Fritz isn’t surprised that so many important questions still haven’t been answered, including the issue of long-term storage of nuclear waste. “It is critical that we bring expenditures back up to €1.5 billion ($2.37 billion),” he says, and he even has a provocative idea to offer: “The government should sell extended operating periods for German nuclear power plants at auction and invest the proceeds in research.”

It’s a provocative idea: Use yesterday’s dirty technology to make a clean future possible? Nuclear money for the great efficiency revolution?

Even Foreign Minister Steinmeier, the architect of Germany’s nuclear phase-out, sometimes succumbs to temptation. “Longer operating lives for nuclear power plants would certainly be the easier approach,” he says, but adds: “However, accelerated technology development is much better in the long run and provides us with new export markets.”

There is a technology policy lesson for the U.S. to be learned in Germany’s energy policies. Specifically, yes do everything that you can in the short-term to make energy more secure, more efficient, and more clean — and above all, available. But don’t forget that to invest in innovation, lest you find yourself in an impossible situation.

Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

[UPDATE: Joe Romm replies in the comments: "Roger -- Thanks for catching my C vs CO2 error.those are very hard to avoid. And thank you for this post. I probably should have elaborated on this issue already -- so I'll just do it in a new post, which will take me a few hours to put together. As you'll see, there actually isn't a gap in my math -- there is a gap in Socolow's and Pacala's math that most people (you included) miss. I'll leave it at that, for now, and Post the link when I am finished."]

Readers here will know that Joe Romm has been extremely critical of the idea that we need any new technological advances to achieve stabilization of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations at a level such as 450 ppm. Now Joe helpfully lays out his plan for how stabilization at such a low level might be achieved. It turns out that there is a significant gap in Joe’s math. Even the remarkably ambitious (some would say impossibly fantastic) range of implementation activities that he proposes cannot even meet his own stated goals for success. The only way for him to close the mathematical gap that he has is to rely on – get this — assumptions of spontaneous decarbonization of the global economy (and by this I mean specifically reductions in energy per economic growth and reductions in carbon per unit energy). In fact, the emissions reductions that he needs to occur automatically (i.e., assumed) for his math to work out are larger than those he proposes through implementation.

Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

[Updated: In the comments Skipper points out a units error (Thanks!). That would be 20,000 nuclear plants, not 2,000!]

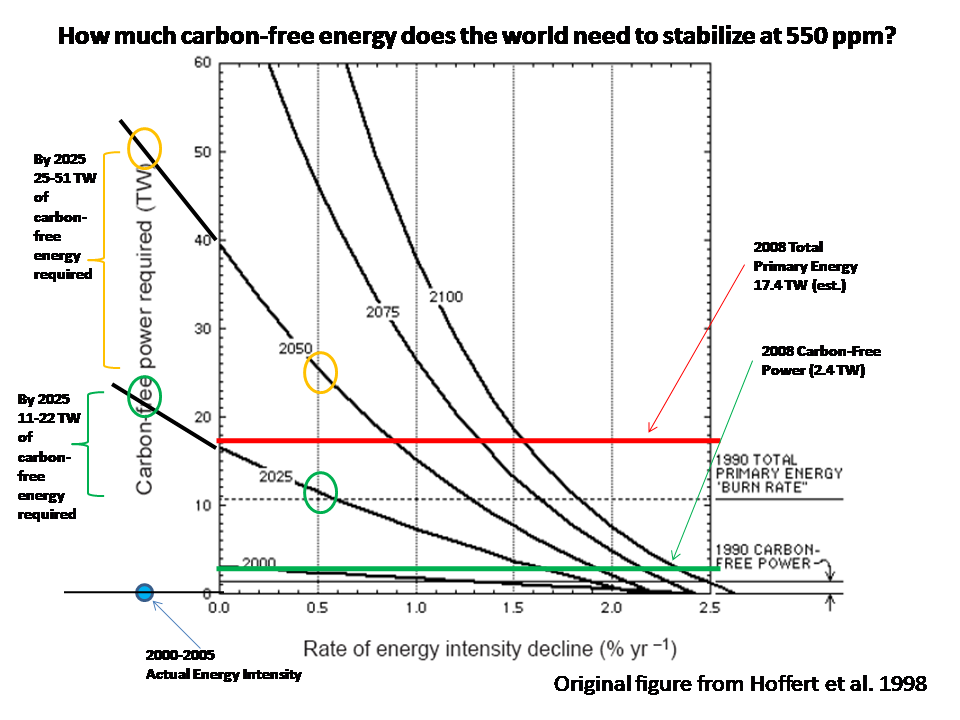

The central question can be found at the bottom of this long, technical post. In 1998 Hoffert et al. published a seminal paper in Nature (PDF) which argued that:

Stabilizing atmospheric CO2 at twice pre-industrial levels while meeting the economic assumptions of “business as usual” implies a massive transition to carbon-free power, particular in developing nations. There are no energy systems technologically ready at present to produce the required amounts of carbon-free power.

Hoffert et al. provide a figure which illustrates the amount of carbon-free energy that will be needed assuming that concentrations of carbon dioxide are to be stabilized at 550 ppm, and the global economy grows at 2.9% per year to 2025 and 2.3% per year thereafter. I have updated this figure to 2008 (estimated) values as indicated below.

Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

Californina Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger provides a positive and optimistic view of of climate policy in a speech yesterday at Yale. You can watch it here. Here is an excerpt:

So I urge you to continue to be open‑minded on our environment. Do not dismiss or do not accept an idea because it has a Republican label or a Democratic label or a conservative label or a liberal label. Think for yourself. This is especially true on environment. So I have great faith in your ability to find new answers and to find new approaches. Don’t accept what the old people say. Don’t accept the old ways. Don’t accept the old ways or the old politics of Democrats and Republicans. Stir things up. Be fresh and new the way you look at things.

Is a post-partisan climate politics possible?

Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

Joe Romm has continued his hysterical, content-free attacks on me and my colleagues for daring to suggest a view not 100% the same as his own. How dare we. After taking a close look at some of Joe’s writing, it turns out that he seems to agree with just about everything I’ve written on energy policy, and his continued (mis)characterizations of my views simply don’t square with what I’ve actually written.

Here are some examples:

Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

Nicholas Kristof has a column in the Sunday NYT on the recent Nature paper by Tom Wigley, Chris Green, and me. Here is an excerpt:

Three respected climate experts made that troubling argument in an important essay in Nature this month, offering a sobering warning that the climate problem is much bigger than anticipated. That’s largely because of increased use of coal in booming Asian economies.

For example, imagine that we instituted a brutally high gas tax that reduced emissions from American vehicles by 25 percent. That would be a stunning achievement — and in just nine months, China’s increased emissions would have more than made up the difference.

China and the United States each produces more than one-fifth of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions. China’s emissions are much smaller per capita but are soaring: its annual increase in emissions is greater than Germany’s total annual emissions.

Please read the whole thing.

And if you are new to our site — Welcome! — and you can find our Nature paper here (in PDF), a short essay on adaptation here (in PDF), and my book The Honest Broker, here.

Posted by: Roger Pielke, Jr.

For those of you who might wish to place the plans announced by President Bush yesterday into context, according to data from the US EIA (xls):

US CO2 emissions from 2026-2030 are projected to increase by only 0.84% per year. So stabilizing at 2025 levels is not an ambitious goal, given the small rate of increase projected to be occurring for the US at that time. To put this another way, the average annual increase in US emissions from 2025 to 2030 will be equal to about 2.5 days of China’s projected 2030 emissions also using projections from the EIA (which in fact probably represents a dramatic underestimate of where China’s emissions are actually headed, as we suggested in Nature two weeks ago). For those wanting to spin things the other way, you might point out that the proposed five year effects on carbon dioxide of Bush’s plans 2026-2030 are about twice the magnitude of the proposed five year effects of the Clean Development Mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol.