A very important new paper is forthcoming in the journal Climatic Change which has been published first online. The paper is:

P. Sheehan, 2008. The new global growth path: implications for climate change analysis and policy, Climatic Change (in press).

The paper argues that:

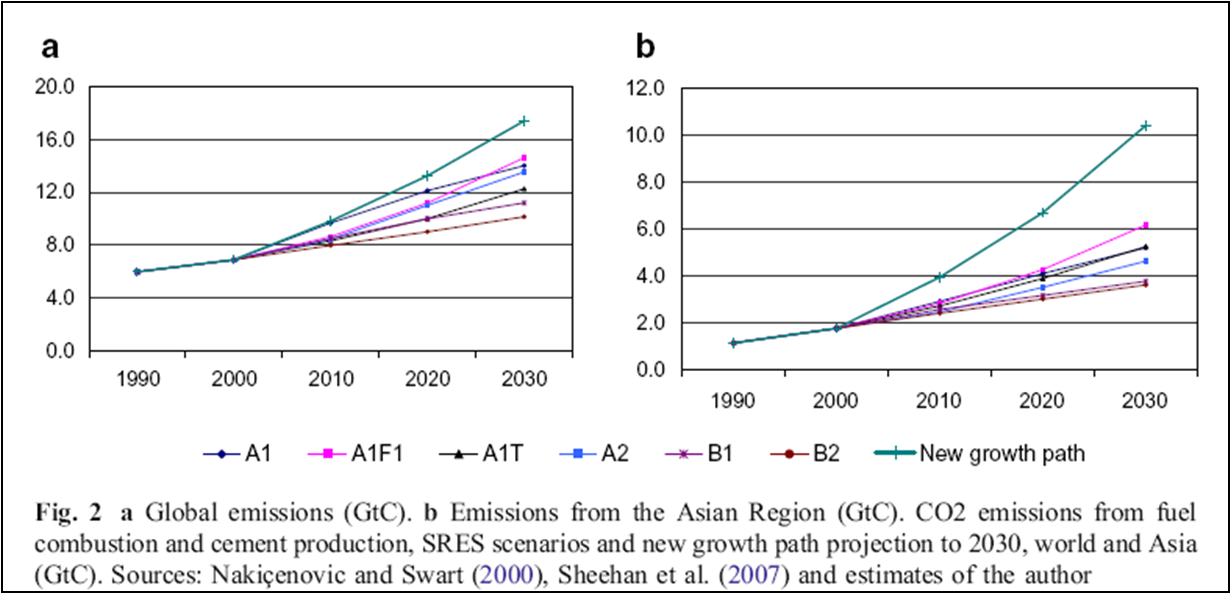

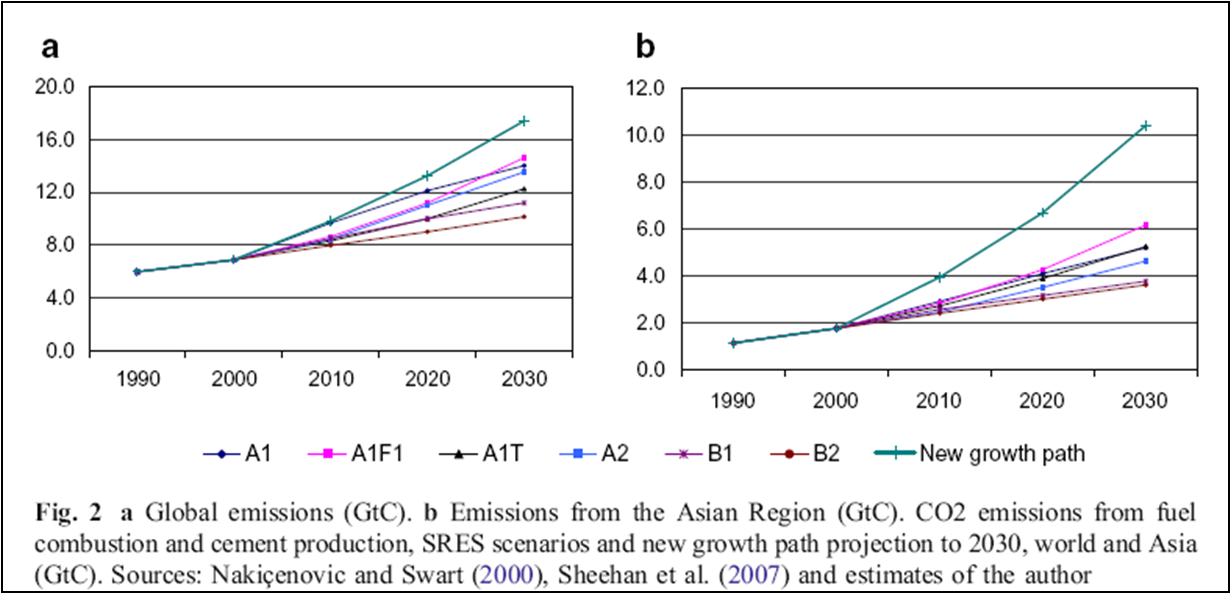

In recent years the world has moved to a new path of rapid global growth, largely driven by the developing countries, which is energy intensive and heavily reliant on the use of coal—global coal use will rise by nearly 60% over the decade to 2010. It is likely that, without changes to the policies in place in 2006, global CO2 emissions from fuel combustion would nearly double their 2000 level by 2020 and would continue to rise beyond 2030. Neither the SRES marker scenarios nor the reference cases assembled in recent studies using integrated assessment models capture this abrupt shift to rapid growth

based on fossil fuels, centred in key Asian countries.

This conclusion strongly supports the analysis that we presented in Nature (PDF)not long ago, in which we argued that the mitigation challenge was potentially underestimated in the so-called IPCC SRES (and pre- and post- SRES) scenarios due to overly aggressive assumptions about future trends in the decarbonization of the global economy. Such overly optimistic assumptions are endemic in the literature, found in the Stern Review, and IEA and CCSP assessments, among others.

Sheehan comes to similar conclusions:

To the extent that NGP is a reasonable projection of global trends on current policies out to 2030, it follows that all of the SRES marker scenarios seriously understate unchanged policy emissions over that time, and do so because they do not capture the extent of the expansion in energy use and emissions that is currently taking place in Asia. Nor, as a consequence, do they capture the rapid growth in coal use that is also occurring. . .

The SRES scenarios were a substantial intellectual achievement, and have stood the test of time for almost a decade. But the central feature of global economic trends in the early decades of the twenty-first century—the new growth path shaped by the sustained emergence of China and India, in the context of an open, knowledge-based world economy—could not be foreseen in the 1990s, and is not covered by these scenarios. Many of the SRES scenarios are no longer individually plausible, and as a whole the marker scenarios can no longer be said to ‘describe the most important uncertainties’. As a result, and especially given the emissions intensity of the new growth path, there is an urgent need for new approaches.

Unfortunately, a major obstacle to discussing (much less achieving) new approaches are the very public intellectual and political commitments that have been advanced, based on the earlier assumptions. Unwinding these commitments — as we have seen — will take some doing.

PS. See also the NYTs Andy Revkin and Elisabeth Rosenthal on China’s growing emissions here. As yet, the dots remain to be connected between such trends unfolding before our eyes and their incongruity with assumptions in energy policy assessments. But reality and policy assessments can diverge only for so long.